Stony Brook-led published research centers on use of a bacterium to trigger immune system response

A research team investigating the use of the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes against colorectal cancer has discovered a way to build a modified version of Listeria as an oral vaccine to prime the immune system directly within the gut, where anti-tumor cells are then generated. Details of the work, led by Stony Brook immunologist Brian Sheridan, are published in the Journal for the ImmunoTherapy of Cancer.

Colorectal cancer is among the most dangerous and deadly cancers worldwide. The American Cancer Society projects there will be more than 150,000 new colorectal cancer diagnoses in the U.S. in 2026, with more than 55,000 deaths. Cancer immunotherapy represents a treatment strategy that harnesses a person’s own immune system to combat cancer. Immunotherapies are used to treat a small proportion of colorectal cancers. However, most colorectal cancers are not responsive to current immunotherapies.

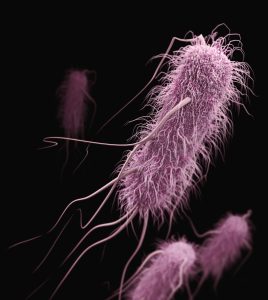

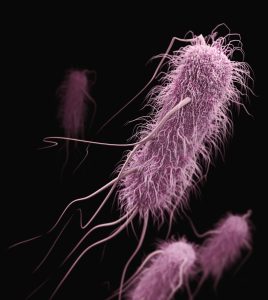

Listeria is a bacterium that can cause infection, but its promise as an immunotherapy for several types of cancer, including colorectal cancer, has reached pre-clinical and clinical trials.

By modifying the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, researchers are developing a promising vaccine against colorectal cancer.

By modifying the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, researchers are developing a promising vaccine against colorectal cancer.

Credit: CDC/Unsplash

This new research, using a murine model of colorectal cancer, is different from previous Listeria vaccine approaches, which were administered intravenously. This method involves the use of an oral delivery approach to generate a robust anti-tumor CD8 T cell response within gastrointestinal tissues. Additionally, the method provides a more targeted approach than traditional immunotherapy methods, as the vaccine directly targets the gut and intestinal tissue where colorectal cancer emerges.

According to Sheridan, associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in the Renaissance School of Medicine (RSOM) at Stony Brook University, a research scientist in the Stony Brook Cancer Center and the senior author, the research team engineered a highly attenuated strain of the bacterium by removing key virulence genes but allowing access to the intestinal immune system. This enabled them to stimulate an anti-tumor response without causing listeriosis.

In mouse models, the vaccine remained contained within the intestinal tissues and did not spread to other organs or cause significant side effects, such as weight loss. This localized approach ensured the immune system of the model subjects reacted to exactly where the cancer develops, essentially targeting the colorectal cancer cells. This process also minimized damage to healthy off-target tissues.

“The clinical significance of our laboratory findings is underscored by the vaccine performance in treating established tumors,” said Sheridan. “While this vaccine alone initially curtailed local tumor growth, its true potential was revealed when combined with existing immune checkpoint inhibitors. This combination therapy led to profound tumor control in the model and suggests that the vaccine can effectively ‘turn on’ the immune system in tumors that were previously resistant to standard immune therapy,” he explained.

Furthermore, the method specifically demonstrated that oral immunization coupled with immune checkpoint inhibitors induced the accumulation of tumor-specific CD8 T cells in the tumor environment. These specialized immune cells remain stationed in the gut and provide immediate and long-lasting protection against cancer cells, a response that was not achieved through vaccination or immune checkpoint inhibitors alone.

“Ultimately, such a strategy could significantly improve the prognosis for patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer who have limited therapeutic options otherwise,” emphasized Sheridan. “Additionally, this method could pave the way for a new generation of cancer vaccines that could both prevent the onset of disease and enhance the efficacy of existing immunotherapies in clinical settings.”

The research team included scientists from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in the RSOM and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. The study was supported, in part, with funding from the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Research Foundation for the State University of New York and several charitable foundations.