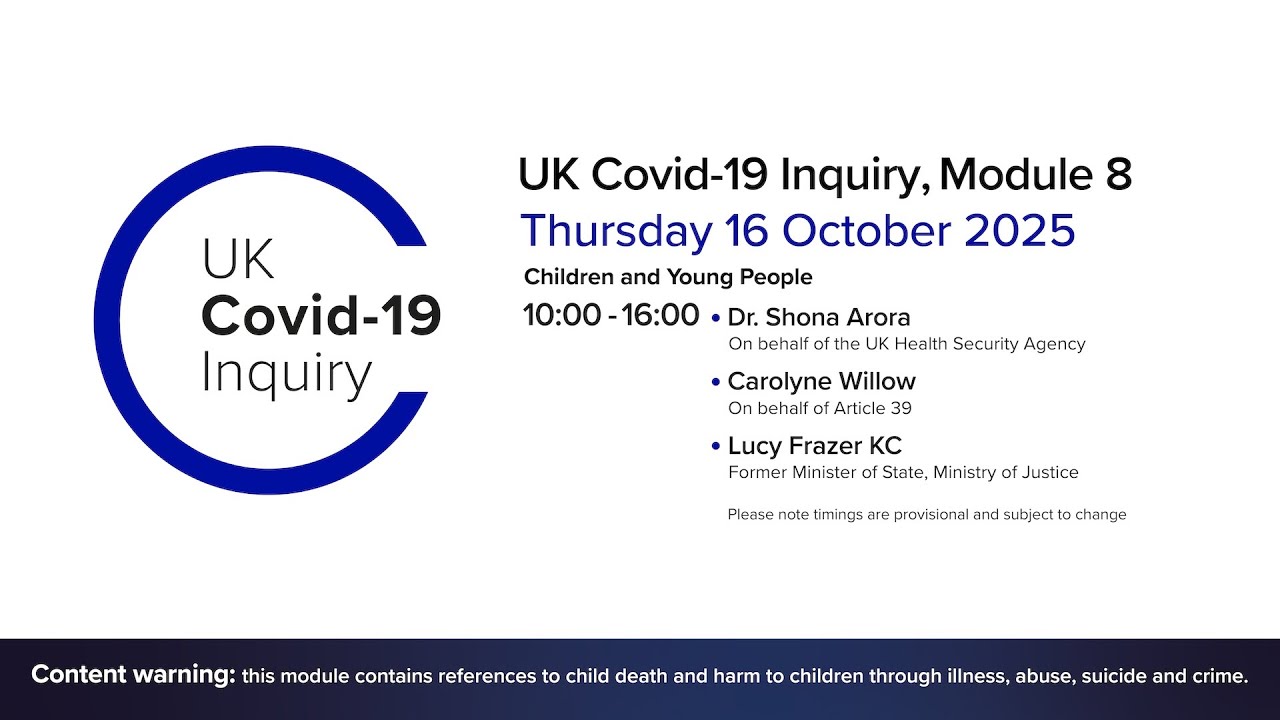

My lady, may I call Dr. Shona Aurora? Repeat after me, please. do solemnly, sincerely, I do solemnly, sincerely, and truly declare and affirm declare and affirm that the evidence I shall give that the evidence I shall give shall be the truth shall be the truth the whole truth the whole truth and nothing but the truth and nothing but the truth. Thank you. Thank you for coming along to help us. Thank you. Please could you give your full name? My name is Dr. Shona Aurora. Dr. Dr. Aurora, you should have in front of you a witness statement that you prepared uh for the inquiry and it is INQ 0000588110. You are the um director of health equity and clinical governance at the UK Health Security Agency. Is that right? Uh that’s correct. I’m also uh since September the 22nd of this year, the interim chief medical advisor for UKHSA for the moment as uh the post holder for that. Doc, Professor Susan Hopkins is now UKA’s chief executive officer. So I’ve stepped up to provide some cover in that role as well. You are just wondering if you could can you get closer to the microphone? Is that better? Yeah. Sorry, I have a soft voice. I’ll try and speak up. Thank you. You are a trained medical doctor. Is that right? That’s correct. Okay. And you worked at um Public Health England during the pandemic, which is the predecessor organization to UK HSA. Is that right? That is correct. Yes. And what was your role at PHE during the pandemic? Um, so during the pandemic I uh was working part-time. My permanent role at that point was deputy director for public health workforce development. Uh but during the pandemic, one of the the roles I took on was um supporting a parliamentarian cell telephone helpline from about April through to July 2020 before returning to my substantive role to assist with the public health reform program. in today in your evidence I’ll be asking you some questions about PH’s role during the pandemic covering various topics but so that we’re clear you’re giving evidence today um from Public Health England’s corporate perspective not um on matters that you yourself personally were involved in. Is that right? That’s correct. I had um very limited direct involvement in the the COVID pandemic apart from my role in the parliamentarian cell. Okay. And the parliamentarian cell that was giving advice to members of parliament uh to to them and to their offices um and case workers um a lot of uh MP’s offices were particularly at the beginning receiving a lot of queries from their constituents. So this was one of the helplines PHE established to try and support and get information out to the public. Okay. Um turning then to PH’s role during the pandemic. Um PH provided scientific research and advice to inform government decision-making and policy development. Is that right? That’s correct. and PHE also produced evidence-based guidance. Um, and that advice was provided to government in a number of different ways, including by members of PHE participating in SAGE, for example, also at a local level participating in local, pardon me, local action committee meetings. Is that right? That’s correct. Okay. What the inquiry is particularly interested in in this module is advice and guidance that PHE produced touching on the provision of education to children during the pandemic and on um the detention of children in prison. But before I move on to those topics, um there’s one matter of general um background that I I’d like to explore with you, and that is whether PHE had a controlling say on the content of all public-f facing health guidance under the so-called triple lock system. So, Dr. Aurora in a witness statement which we don’t need to pull up but a statement of Elizabeth Kit from the Department of Health and Social Care. Um and the reference for the transcript is inquiry trip0652113. In that statement, um, Miss Kit describes a triple lock system which meant that public-f facing health and behavioral guidance from about May of 2020 had to be agreed between this chief medical officer, the cabinet office, so number 10, and also by senior PHE officials. Is that does that sound right to you? uh that does sound right in terms of who who a piece of guidance would need to go through before it was finalized. Okay. And can we take from that that for example some department for education guidance which we’ll come on to um on school attendance would have been agreed also by senior PH officials. It it would have the health components of DfE guidance would certainly have uh been uh put in front of PHE officials to comment on. Okay. Before we go on um to um guidance touching on education, I’d like to cover with you a topic which um is infection control measures to make schools safer in a future pandemic. So something that we’ve referred to in the inquiry as a safer schools topic. And before we go into the detail, there are different names and acronyms for these measures. Um, but so that we’re clear, I will use the term NPI, so non-farmaceutical interventions. That is the terminology that the inquiry has used most often. Um, so we’re not talking about vaccines here, but other measures like social distancing, cleaning, masks, ventilation, air cleaning, for example. H firstly, what is the evidence um what is the standard of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of infection control measures deployed during the pandemic? You deal with this at paragraph 5.12 to 5.15 in your witness statement. Um and and what you say there is that there isn’t good evidence at present showing which measures in particular were effective. Is that have I understood that correctly? I think um so this is based on a systematic review of available evidence uh that reviewed the literature up to January 24 and particularly in the context of schools and education. um the evidence base is not the highest quality and that’s for a number of reasons including um the difficulty of studying this in real time and the fact that um it’s quite difficult to disentangle the impact of one particular NPI from another because in many cases NPIs are implemented or as a as a package. Um so uh there is if you like it in in the context of strength of evidence and and the science and evidence space it is uh not gold standard by any means and was uh lesser so pre- pandemic. That might be uh thought as being quite surprising that several years on from the pandemic where extensive use was made of NPIs in schools for example guidance given about the um system of controls um face masks handwashing bubbles that sort of thing. So am I right in thinking that still now we don’t have we don’t really know which measures from that selection actually worked to prevent the spread of the virus. Um we probably don’t know with huge certainty. So if I took um for example a comparison with um a clinical measure like vaccination and um where you can thoroughly test out through a clinical trial and what we might call a randomized control trial where you can correct for bias and uh other issues. A lot of our evidence is based on what we call more observational studies in in the real world. So studying what’s happening in populations. But it means we’re less good at accounting for things that might actually be influencing the effectiveness or an outcome. Um because we don’t always know how to control for them or identify them. Um we sometimes use modeling studies as well to inform the evidence base. Um but again that that models are only as good as the assumptions that we put in and they also rely on having some basic data around for example the biological behavior of a particular pathogen. Um so if I compare it to the gold standard of RCTs and and sort of more clinical interventions RCTs are sorry randomized control trials where you can control more successfully for those unknown variables that might be the cause of why something is more or less effective which you can’t do in an observational study in the real population um uh as easily which means you can sometimes get a result and make an associ ation that that’s some that could be really effective but actually it might be due to something else that you haven’t been able to account for. I see in your statement I think you also mentioned that it’s it would have been unethical to create a sort of control group during the pandemic and withhold interventions from that group that might have given you a better idea of what interventions were working but the ethical boundaries meant that wasn’t possible. Yes. And that’s and and all research and trials do have to go through an ethical process. Um but if if there’s something that you think would genuinely help and save lives sufficiently that would stop you denying people from that or population from that and that’s the situation we were very much in. Okay. You mentioned a moment ago a rapid review uh and I’d just like to take you to that um quickly. The reference is INQ0651524. Thank you very much. And we can see here this is just the front page. Um so it’s the effectiveness of non-farmaceutical interventions as implemented in the UK during the COVID pandemic. A rapid review. Just before we move to the conclusions, can you just tell us what what a rapid review is exactly? Um so it it is a a review of existing evidence and studies and trials carried out usually more rapidly. So so to actually do this properly can usually take months and months to to go through. So obviously we don’t have time in in a pandemic situation um or even in an outbreak situation of uh and something relatively new like EMPOX. So we have uh an approach that that uses particular techniques that allow you to still produce something of reasonable high quality to define the scope sufficiently, specifically and narrowly enough of the review, but also then to search sufficiently to gather um a range of materials. And those are then uh brought together and synthesized to try and establish whether or not you can conclude of the direction of travel in favor of a particular intervention or group of interventions or otherwise or in particular settings. Okay. Or otherwise. So you’re doing a sort of scan of the evidence that’s available and working out roughly what the state of play is, whether there’s good evidence to support something or not. Yeah. Okay. And this particular rapid review, this wasn’t conducted during the pandemic. This is evidence up to, I think you told us, 2024. Is that right? Okay. So, if we can turn then to page uh 28, please. And uh thank you very much. The conclusions that we’re interested in are consistently with other reviews, we found that the validity and reliability of the available evidence to support the effectiveness of individual NPIs to con to control the spread of COVID to be weak and not to provide robust evidence to inform future pandemic preparedness. And so that we’re clear, the NBI that were reviewed um those included ventilation and air filtration. Is that right? Um I need to check in detail on that one. It’ll be in one of the tables. Um but I I know I’ve also looked we’ve referenced the McMaster living and that’s also looked at ventilation in uh and um they they looked in a number of community settings and their latest living evidence review. uh I identified studies in just two educational settings that arranged. So we will come on to in a moment evidence specific to ventilation air filtration. Um but focusing now on this sort of rapid review. Um, it says to continue, “The main lesson from this review is the need to improve evidence generation to support future pandemic decision-making, including building rapid evaluation into the response to the pandemic and other public health emergencies. This includes the development of sleeper study platforms and protocols which can be activated during an epidemic or a pandemic. Um another approach is the delivery of rapid adaptive trials for the simultaneous testing of various NPIs. Um can you help us in sort of plain language um what is needed in um future pandemic planning to help us plug this gap in knowledge? You can take that down now. Thank you. Okay. So I think what we’re what the initial opening sentence said was what we’ve discussed which is um the quality of the evidence is not as strong to give us as much confidence as we would like where one way we could address that looking forward. It takes time to set up studies um which will inform the evidence and uh we can work on trying to design the frameworks for those studies and develop protocols that we wouldn’t activate now but would be on the stocks um and use peace time to more thoroughly test out the methodologies that we might use because obviously in a pandemic if you’re starting from scratch then um designing something from scratch you’re more likely to not thought through where biases might be and how you might correct for them. So, so that’s the idea behind that. The other approach is to have something um uh the other approach referred to is something that as you go through the trial, you you bring in different elements and and you create a more agile approach to looking at at what you’re trying to do sequentially. Is that something that UKHSA is undertaking at the moment? um it’s something we amongst others are are are looking at and part of the research uh community. So through the National Institute for Health Research and the UK research and innovation um approach and through the DHSC uh research framework for pandemics um is is something that’s being developed through the current pandemic preparedness work stream. Okay, I’m going to move on now to a different topic, which is whether plans to make schools safer in the future ought to focus on airborne pathogens. Um, you’ve dealt with this in your statement um at paragraphs 5.2 to 5.7. Um but can I just ask you generally whether plans to make schools safer should focus on pathogens which are transmitted through the air as opposed to pathogens which are transmitted via other roots of infection. Um so overall our pandemic preparedness framework for the UK focuses on five roots of transmission of which respiratory is one. Um it’s fair to say that five out of the six pandemics that have occurred since the 20th century have been respiratory and airborne. Uh and uh on I think our national risk register also signals that’s still the highest risk. So it would certainly make sense to start with um prioritizing that. However um there are potentially still other roots of transmission that could cause a pandemic. So we do need to be mindful of that and be thinking about those routes as well and not not be completely focused but as a priority to start with that would would be one that is probably the most likely. Okay. I’m going to take you now to um the witness statement prepared by professor sir Chris Witty um which deals with this topic and just see if you agree with his conclusions. So his reference is for his statement is triple0588046 and we’re looking here at paragraphs 7.5 to 7.6. The statement is the root of transmission is also important. Touch and fico oral transmission may be more likely in children and especially younger children than young adults. CO 19 was a respiratory pandemic but other routes of transmission would have different implications for the relative safety of and proportion of the transmission to and from children. Respiratory transmission remains the most likely route of pandemics because of the ease of spread and in practice four of the last five pandemics that affected the UK three influenza and CO 19 were respiratory with only one by other roots and that was the HIV epidemic. It is therefore sensible to concentrate on respiratory roots of transmission. Children are as susceptible to respiratory roots as adults. So, it sounds like you’re on the same page there that it’s the most likely, but certainly you can’t rule the others out, I think. And if we move on then, please to paragraph 7.6. Um, historically, other roots have caused major pandemics affecting children, and there’s no reason why they cannot again. Sexual roots of transmission are much less likely to affect children. Um, and that is why the last pandemic HIV was predominantly a disease of young adults. Vertical bloodborne and breastfeeding transmission of HIV between mothers and babies shows that the transmission between mothers and children is critical there. Hepatitis B which is a sexual and bloodborne virus is transmitted mother to child and is readily transmitted between children in normal play. Young children are more susceptible to touch diseases than adults. A recent example being some um clades of epox in central Africa. Adults touch children in normal caring roles and ch children touch one another much more readily than non-related adults touch one another and preventing touch diseases requires different measures than were used for CO 19 and children are generally less careful in hygiene than adults. So fecal oral diseases such as cholera are often more common in children and again the measures taken to reduce transmission would be different requiring measures related to hygiene and safe food and water. And finally vectorbor diseases are also important in childhood globally such as malaria um with different counter measures but they are unlikely to affect the UK as pandemics in the foreseeable future. So, Professor Sir Chris Witty there is giving us a bit of a rundown of the different roots of transmission, how children can be implicated in them, explaining that even uh illnesses that are not airborne um still will have implications for children and some such as touch diseases would be perhaps more risky for children. Um and so overall other roots of transmission certainly can’t be discounted. I think we can draw that conclusion from his evidence and you would agree with that? Yes. Is that right? Okay. Yes. Thank you. We can take that down. Um you mentioned uh in your evidence um the National Risk Register. Mhm. Can you just tell us briefly what that is? Uh so the National Risk Register is I think owned by the Cabinet Office and it’s our it is what it says on the tin. It’s an assessment of a whole range of risks facing the UK. It’s a publicfacing document. Um, and it sets out risks uh on all sorts of dimensions, not just health. So, for example, cyber security is is is another one. um and attempts to uh rank the not rank but but score the risks based on likelihood and and impact to give some indication of how serious they might be and and which ones are are likely to be the most common. Um and there is a section on health risks in there which includes risk of a future pandemic. And in that planning it is a respiratory pandemic. That’s the predominant risk. Okay. I’m going to move on now to the evidence um regarding ventilation and filtration systems and their effectiveness in reducing the transmission of disease in schools. Um you deal with that in your witness statement of paragraphs 516 to 518 and also 6.8 to 6.12. Um, Professor uh, Katherine Nos has provided a statement to the inquiry and she will give evidence next week touching on this issue, specifically on this issue. Um, and I understand you’ve had a chance to read her statement. Is that right? If we could just pull up paragraph 6.8 of her statement, which is inquiry 0588180. These are her conclusions about the state of the evidence. So she says evidence that demonstrates ventilation or air cleaning reduces transmission of infection or illness is very limited. And she says that is primarily because such data is challenging to obtain for two reasons and these will sound a bit familiar to us after your evidence regarding other NPIs. it. Firstly, she says there is not necessarily a linear relationship between the reduction in the concentration of a pathogen in the air and the reduction in the likelihood of infection. And then if we could just scroll down please um to her second point. Thank you. And she says also direct evidence from intervention studies is difficult to measure. Unlike medical trials where different treatments can be given to individuals and the treatment only affects that person. Ventilation is an environmental measure which affects a building and everyone in the space. As such it may have different effects over a day or season depending on things such as the weather and occupant behaviors. And it’s hard to conduct studies which compare directly between spaces which have different levels of ventilation. And where ventilation is applied in one setting, for example, a school, the same people can be exposed through interactions in other spaces, for example, homes, transport, and social settings, which can reduce or even negate any effects in the intervention. So we can I think readily see that if we had for example a trial in a school providing air cleaning technology but those children travel to the school via bus and are exposed to pathogens in that way it would be difficult perhaps for the scientists to work out exactly how much um benefit the children were getting from air cleaning. Um would you agree with her firstly with Professor No about the evidence that’s currently available to support those ventilation and air cleaning technologies? Um yes around these two paragraphs around Yes. I think that’s a very fair assessment. Yes. Okay. Um and would you agree with her about the reasons for the posity of evidence and that that being that direct evidence is difficult to obtain for the reasons she states and also that the absence of a linear relationship between the reduction in pathogens in the year and infection rates in individuals. Yes, that can be taken down now. But bearing in mind that posity of evidence, um, Professor Nos’s view is that there is growing evidence that indicates that enabling better ventilation and indoor air quality does have a positive effect uh on the health of children. And that’s for reasons um she sets out in her statement of reducing air pollution, for example, or mold in classrooms. Um so bearing that in mind, in your view, should more be done to improve the ventilation and air quality in education settings to reduce um well actually I’ll just stop there. Should more be done to improve ventilation and air quality in education settings in your view? Um so obviously that isn’t a decision for UK to say to make but um I think we’ve heard the narrative that and even from the McMaster living review there is emerging evidence notwithstanding the fact that it’s really hard to get high quality evidence um that indoor air quality matters for a whole range of of issues not just for infectious disease transition uh uh transmission but um for concentration or other matters of of well-being and that includes what’s described as thermal quality. So basically whether you feel too hot or too cold. Um there’s I I think there’s definitely room for extending this evidence base further and I believe there is um a new UKRI funded study called Chile which is for ch children and adolescence health effects in learning environments um that’s been established um led by University College London and UKA will be participating in that as well um and and helping with one element of that and that I think will give us stronger focus on school settings in particular. Um so I think definitely the need to strengthen the evidence base and that’s because I think when you’re applying a universal measure like that it’s obviously there’s a there’s a cost implication. You want to make sure you’re doing the right thing and you want to understand also some of the complexities around some of the interventions. So I think again professor notes refers to um uh sort of anything mechanical needs to be maintained. Um there’s often you know there’s the risk of false reassurance. There are tradeoffs particularly in a classroom environment between noise and uh getting this right. So I think we definitely need to start building that evidence base particularly around some of those specifics so that a decisions can be made and informed by that more appropriately across uh the education sector. Okay. So if I understood you correctly, we need to build that evidence base prior to decisions being made about improving ventilation and air quality and education. Is that what your advice would be as a UKHSA? I mean there is there is existing evidence. Um there is a tradeoff I suppose on what other requests are made on on limited resources. The schools estate is very mixed. Um I think there I think the point that’s also made is making sure that that we have good building standards in place for partic and I think that’s much easier to do with new builds. Um I think some of the challenges is around retrofitting but I think we just need to be careful that we are making sure that any investment is really going to produce the outcomes uh that are needed. While we’re still on the subject of ventilation in schools and um building standards, in your statement you confirm that during the pandemic, now we’re going back now to 2020. Um uh during the pandemic, guidance on ventilation specific to schools wasn’t provided by PHE. Schools were referred to general guidance on ventilation which covered um businesses I think in non-domemestic settings. Professor No in her evidence makes clear that schools have certain unique features which are relevant to the transmission of pathogens. So for example um schools are unlikely to have mechanical ventilation as businesses might have or offices might have and schools are obviously used by adults and children together. Uh and some non-farmaceutical interventions like maskearing might be difficult for children to comply with to use appropriately. Um would you agree that ventilation guidance specific to schools ought to have been given uh by pH during the pandemic? So I think this is quite a difficult one. And I think if we go back to the start of the pandemic and what we knew about um the virus at the time, uh there was a stronger focus on droplet spread and less less so on um aerosol spread um and therefore a stronger focus on uh the measures that you would normally apply in in that case. Um I think the other thing is we were we knew there was guidance being produced by DFE for schools and that I think that that would have been the appropriate place to address that as the evidence base emerged. Um so I think we as PHE were providing much wider principles that could be used. Um there was also advice again more general and not specific to schools through the health and safety executive. Um but I think in the early stages when we didn’t really know the role of ventilation that it might play. I think um it it was difficult to have specific guidance at that point on ventilation and later on I think it was picked up through the guidance produced by DFE. But if PHE was referring schools to generic guidance, um, appreciate not as much was known at the time about transmission rates, but come at a certain point it was clear that airborne transmission was a factor and PH did refer schools to ventilation guidance. Um there’s no good reason is there for referring them to guidance which is applicable to offices as opposed to specific guidance relevant to schools. I I think at the time that reflected what we knew in terms of the evidence base which was um slightly stronger on a on multiple other settings as I’ve said the evidence base around school settings um was quite thin and and is has improved because the pandemic has provided some opportunity to do that and um again I think what we would see our role doing is then supporting sectors uh to produce produc specific guidance for those sectors that reflected the evidence base but could then be more tailored to the sector understanding of of and sector context. But you would have had input in in DFE guidance touching on um health measures. That’s right, isn’t it? Okay. But if I’ve understood you correctly, what you’ve also said is that there wasn’t enough uh there wasn’t an evidence base at the time to enable you to to develop guidance specific to a school setting. Have I understood that correctly? Certainly at the beginning. Yes. Okay. Um I’d like to move on now um to uh the measures um to pardon me to the recommendations made by Professor Nos which touch on areas of uh UKHSA’s responsibility. So one of the um recommendations that Professor Nos makes is that there should be more effective monitoring with long-term data collection. So she cites an example of um schools in the United States which had CO2 monitors and they were able to feed back information in real time um to a central data collection um point um so that uh there could be a long-term monitoring of the effectiveness of measures put in place. Um and Professor Nos u makes the recommendation that we have that long-term data collection across public buildings supporting building the evidence base for environmental impacts on health. Um is that something that um would sit within UK HSA’s purview um spearheading that the development of that long-term data collection? Um, I think it wouldn’t necessarily be us to spearhead. I think we we’d certainly be there to support and I’ve alluded to our role in the the Chile hub um to support. Again, DFE I think are taking um a leadership role and have provided schools with carbon dioxide monitors um and are looking at that. And there is another study that we’re awaiting the publication of which will also help to inform approaches. Um it’s now called the Bradford class study. Uh which again DFE have been very instrumental in. So I think we would potentially have a supporting role um alongside other academic institutions and other bodies um with engineering and building expertise. uh but for the school sector I think DF are absolutely critical in this. Um just taking a step back it seems that there’s various um government departments and academic organizations that could be involved in in um managing the school environment. You mentioned environmental expertise. Um we know also that the department for education issues guidance for example on building design. Yes. Um UKHSA is responsible for guidance on health protection measures within schools. So one gets the impression that there is a sort of group of actors um that have shared responsibility in this sphere. Where would you say or would where would UKHSA say in government lies the overall responsibility to consider future NPI measures in schools? So I think the responsibility has to sit with the government department responsible for that sector because um there’s obviously schools but there’s businesses there’s there’s all sorts of other sectors um I think our role in UKSA is to support with advice bas evidence-based advice um carrying out evidence-based reviews contributing to the research where we can using uh our data and surveillance to identify issues that might be coming up to provide an input into where we think the gaps are in research and evidence and in appropriate interventions. So if we’re talking about schools in particular, I take it from your answer. You would say that it’s DFE who hold the overall responsibility for um considering future NPI measures in schools. And UKHSA’s role would be to support with advice, but perhaps from what you’ve said, UKHSA would also be responsible for prioritizing the kind of studies that are needed to plug the gaps in knowledge. And again, I don’t think we would do that alone. I think we’d be one of uh a number of of contributors uh with expertise in this field through the academic roots and the academic uh structures and governance that exist to support this. I see. I’m going to move on now to another topic and that is the guidance given to clinically vulnerable and clinically extremely vulnerable children and young people. Um we’re focusing here in this module on children. So I’m I’m really going to focus on the guidance that touched on school attendance. Um, just to set the background, in March of 2020, PHE issued guidance on shielding. Um, we don’t have to pull that up, but that guidance advised those with certain specific conditions who were clinically extremely vulnerable to shield for 12 weeks from the receipt of of a letter. um the guidance in that first iteration it didn’t distinguish between adults and children but it said at the end that the guidance applies to clinically extremely vulnerable children. So that was the beginning. If we move forward then to May of 2020 the department for education issued guidance concerning clinically vulnerable and immunompromised children and young people. And we know just before we go to it um Julia Kinnibberg from the Department for Education uh in her statement she says that that guidance was completed with PH’s assistance but we know from what you said earlier that PHE would have had input on that public facing guidance in any event um under the triple lock procedure if I’ve understood your evidence correctly. Um so if we move to that guidance now it’s INQ0542889. Um so it it was termed supporting vulnerable children and young people during the corona virus outbreak actions for education providers and other partners. And then if we scroll through please um particularly to page five. Yes, the summary of attendance expectations for vulnerable children and young people. So, this was May 2020. Um, the lockdown had been in place um for over a month approaching two months. This is uh attendance expectations for vulnerable children. Now, so that we’re not confused, this is talking about vulnerable children under the sort of Department for Education’s definition. So, not That’s not about clinically vulnerable children, but about children who were um required to attend school because they had, for example, a social worker or an EHCP plan or were classed as otherwise vulnerable. And so this guidance is setting out attendance expectations for them. And it says that their attendance is expected. And if we go to the first bullet point there, it says for vulnerable children and young people who have a social worker, attendance is expected unless the child or household is shielding or clinically vulnerable. And so the shielding reference there would be to children who are clinically extremely vulnerable, I would imagine. But there’s also the separate category of children who are clinically vulnerable. Do you see that? Yes. Okay. Um and then if we turn over the page uh to page six under the first bullet point there’s further guidance which says for all these groups of children education providers local authorities social workers parents and carers and other relevant professionals um should work together closely to consider factors such as the balance of risk including health vulnerabilities, family circumstances, and risks outside the home. Um, and the child or young person’s assessed special special educational needs were relevant. Um, so it’s giving parents and also other adults with responsibility for that child. um is giving them permission if you like to weigh competing interests including their health vulnerabilities in deciding whether attendance is appropriate for those children. We can take that down. Now in your witness statement um you explain that the category of clinically vulnerable as opposed to clinically extremely vulnerable was rem removed as regarding children in May of 2020. So we can go to your witness statement um inq00588110 paragraph 3.94 deals with this and it says while a cohort of children was considered on a precautionary basis to potentially fall within the CEV group when it was originally defined the guidance in relation to CV children was reviewed by the RCPCH that’s the Royal College of Pediatric and Child health and the NHS clinical director for children in early May of 2020. The conclusion they reached was that the middle ground category of CV was not meaningful as applied to children who were either clinically extremely vulnerable or not at materially increased risk from contracting the virus. And it was agreed by the UK CMOS that only those children with significant neurodedevelopmental and other specific conditions needed to be advised to shield. Um and I just can you help us with why the DFE guidance issued in May referred to clinically vulnerable children um whereas it seems we don’t have the exact date but here it says in early May that category was made obsolete as regards children. Um, so I think it was uh it’s hard I I wasn’t part of these discussions at the at the time. The clinically vulnerable clinically extremely vulnerable program was led from the department uh because it did require significant input from clinicians in the NHS. Yeah. Um I think probably it was a matter of timing um because I think it was June before that evidence uh which I’ll sort of talk about later on at 3.95 from the RC PHC came uh was perhaps more strongly uh made available. Yeah. Um so I think sorry we can just we thank you very much. Uh we’ve got it up here. We can just have a look. Okay. This is on the 12 10th of June, pardon me, of 2020. The RCPCH announced updated advice for clinicians on shielding children and young people. And that advice emphasized that according to the new guidance, the majority of children with conditions including asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, and kidney disease do not need to continue to shield and can, for example, return to school as it opens. uh and this includes many children with conditions such as cerebral palsy and scoliosis for whom the benefits of school in terms of access to therapies and developmental support outweigh the risk of infection. So I think what this is showing is this is a an illness that we haven’t had much of a chance to know much about. It’s moving quite quickly as clinical evidence of im severity was emerging. um uh that evidence was being used to assess what was appropriate um for different groups of children and young people. Um but uh we’re talking about sort of May 2020, June 2020. So I think that just illustrates particularly at the beginning how fast moving things were and again coming back to initially the the at the beginning I think the thought was to be a bit more precautionary which was why there was a wider net cast but clearly the implications of shielding and particularly for children and young people are huge. So being able to limit that to the ones who are really going to where the benefits really are going to outweigh any harms was really important which is why I think um the sort of work being done by the RCPCH and through uh the NHS and and the CMO was was really important and being done at pace whilst at the same time we’ve got you know from March to May the the the still taking a bit of a more precautionary approach. Okay, we can take that down now. Thank you. Um, and can you tell us did Public Health England agree with the RCPCH and NHSC that the clinically vulnerable category was not meaningful as applied to children who were either CEV or not at materially increased risk? So in in the context if I can just step back and and look at how the clinically vulnerable cohort and and program was dealt with. It was as I say led by the CMO office. Um and it pulled in advice from public health England but more around the epidemiology and and those aspects. the decisions around clinical categorization really uh needed to be led from the right areas. Uh so NHS England and clinical directors which is not PH’s area of expertise. Um so I think uh we would have accepted particular it was more important that the CMOs were happy with uh the evidence that they were being presented with through uh their the clinical community. I see. Well, we will be hearing from uh Professor Sir Chris Witty next week. Uh we can ask him about that. Um there’s one other matter of clarification I’d like to ask on this point before we move on. Um CVF families a core participant have asked for clarification. um their understanding is that children who had been clinically extremely vulnerable were sort of downgraded to being clinically vulnerable in September of 2021. And so their um understanding is that the clinically vulnerable category was not removed for children, but it was now the category that all the previously clinically extremely vulnerable children moved to. And before I ask you to to answer that to give us your thoughts on that, I I’d like to move to the guidance if we could pull that up. um which is INQ0348076. So this is guidance from both the department for health and social care and PHE from September 2021 and it it’s the guidance which um indicated that children should no longer be classed as clinically extremely vulnerable. And if we can move to page three of that, it says here, what has changed? Recent um clinical studies have shown that children and young people are at very low risk of serious illness if they catch CO 19. As a result, children and young people under the age of 18 are no longer considered to be clinically extremely vulnerable and should continue to follow the same guidance as everyone else. A small number of children and young people will have been advised to isolate or reduce their special social social contacts for short periods of time by the specialist due to their general risk of infection rather than because of the pandemic. um if this is the case for your child, they should continue to follow the advice of their specialist. With that guidance in mind, can you tell us is it correct that children who had been clinically extremely vulnerable were downgraded into the category of clinically vulnerable? Uh I don’t that’s not my reading of this particular guidance. Um I think what I think there’s beginning to be a move away generally from overuse of clinically extremely vulnerable um as you know vaccine programs came on stream we had better treatments um and uh I think what this was beginning to do is trying to return to a bit of a a new normal. So, so there will always be a small group of children who because they’re very immunosuppressed or um are undergoing chemotherapy or something like that will be at risk of any infectious disease. And I I think what this was beginning to say in the context of the what we understood to be the overall impact and severity of uh COVID 19 in children um those children uh their susceptibility should be ma to co should be managed in the same way that you would manage them in terms of their risk of any infectious disease uh which they could equally well be um very prone to. So that’s uh I think what it’s acknowledging that there are always going to be a small cohort of children who are very vulnerable to uh infectious disease either acquiring it or or suffering more severe consequences. Um but that’s true of other infectious diseases and not just COVID. So I I don’t think it was about downgrading from CV. I think it was trying to assist in how we manage a return to integrating COVID into how we manage other infectious diseases as we start coming out of the the more serious waves of the pandemic. Thank you. Um one final uh question on this point. Um we’ve had evidence uh from um Miss Lara Wong from uh co um clinically vulnerable families um and their organization uses a part of the green book which is a UKHSA publication um which provides guidance in relation to immunizations and it contains certain criteria for children who are classed as clinically vulnerable to COVID. Um, and I think there’s some confusion here about children being classed as clinically vulnerable when it comes to vaccines but not for example when it comes to schools. Um, can you help us why might there be a categorization of vulnerability in relation to vaccines and not not in relation to schools? Um it I I think I guess it depends on the the answer to that is it’s the questions being posed are different. So, so vaccine prioritization is determined by uh or recommended by the joint committee on vaccination and immunizations of which uh PHE and now UK catch are are a member and provide support um but consists of a range of other experts and um they will be looking at the evidence of how effective vaccines a vaccine would be in uh either reducing transmission or preventing a severe outcome. Um, and that might be different from uh in a school setting, the question you’re asking is how safe is it for this child to be in school in the round? What are the tradeoffs by them not being in school? What harms are they experiencing uh by being taken out of that setting? Um and uh what are the mitigations if they are in school to keep them safe and and protected? Also as I remember the policy for vaccination um the committee chose the clinical route basically priority was decided the on clinical you may have all sorts of but that was the way they decided and it was based on some pretty sound evidence that yes uh so JCBI tend to base their decisions very much on a very clinical clinic you know what is the biology behind this what is someone’s immune status how are they likely to react to the vaccine the question you’re asking in the context of a school is what is the the best thing we can do for this young person or child to give them the best possible health outcomes and keep them safe in all sorts of ways and protect their development. Thank you. Um PHE issued guidance on the 4th of August indicating that children who were clinically extremely vulnerable could stop shielding and could attend schools when they reopened. um and we don’t need it to move uh to that guidance now. But the position when schools did reopen in September was that all children were required to attend. So shielding was still active but it had been paused at that stage for children. Um and what I’d like to explore with you is whether um the advice on school attendance for children struck the right balance between protecting health but also promoting education. So you’ve told us about this this sort of tradeoffs for young people. Can you uh summarize for us what the evidence shows about the effect of school openings on transmission rates? So again, I think it’s it’s not as straightforward as we would like it to be. There is some evidence uh that says if you open schools you’re likely to see um an an uptick tick in in number of cases. But what the overarching message I would give is that school transmission in schools and and the role of schools in COVID 19 is very much linked to background transmission and rates in the community and and prevalence in the community. So if you’ve got high rates of COVID circulating in the community, um schools are part of that and it’s a dynamic two-way. So if you’ve got low prevalence in the community, schools actually have very little negative impact like they they don’t contribute to transmission going up marketkedly. C can you and this is a slightly different question but can you tell us whether children who attend who attended schools in the autumn of 2020 were more likely to catch the virus than children who did not. So in August 2020 overall community prevalence was relatively low and I think at that stage my recollection was that they were not there was no evidence to suggest that they were more likely to so obviously pre alpha wave but at that point when schools reopened and overall community rates were low transmission rates in school would have been low as well. Okay. And I think you might have misheard me. I said autumn 2020, not August. Does that hold true for September, October? So again, we were just beginning to see the uh emergence of the alpha variant then and so community transmission was beginning to go up but that was across the community and uh not not particularly in schools. Okay. But then again, the sort of slightly separate question of whether children who went to school as opposed to those that stayed home, would they have been more likely, do you think, to catch COVID or or can you not tell us? I think I I couldn’t completely tell you that though. I don’t think there was any evidence that looked at that answering that particular question. And I suppose it depends what you mean by staying at home. If you mean shielding, um, probably because shielding is such a a in any context if there’s any virus circulating and you’re really really isolated. But staying at home doesn’t if if you’re not in that extreme setting doesn’t necessarily mean you’re not going to be exposed to the virus if you’re out in other uh settings or environments and that you’re equally likely to um acquire uh COVID from those. Okay. We know that um tragically there were some deaths of children and young people in England from with each wave of the pandemic. Yes. And um we um can see in your evidence um a study which is at um INQ0413 012 a study which looks at the deaths in children and young people in England after infection. It’s actually very difficult to make out, but the summary at the top tells us um that uh we can see a total of of 99.995% of children and young people with a positive uh test survived. But there were 25 deaths of children and young people due to COVID infection. Um you can see that just above. um it’s not dealt with in this study but we know that children young people were also of course at risk of developing long COVID as a result of infection. I want to ask you overall given the risks of infection to young people and the risk of death. Do you think that the advice on school attendance um struck the right balance between protecting young people um their health and um their access to education? So I think that’s a really it’s difficult to answer because with hindsight and it and also not being there at the time but I think what I would say is it’s often quite you’re balancing a lot of complex issues in the messaging that you’re you’re giving out and you also want to give sufficient clarity about what on balance you think in terms of overall risk um you’re you’re you should be steering members of the public towards. So I think it’s always difficult to get that balance right. Um and particularly at any one point because again in as I said in August things felt very different from November uh of of that year um as well and certainly in December and January. So I think at the time I think it was trying to send a clear signal that uh the data and the evidence that we had on the behavior of that the virus at that stage uh was that um children did experience less severe disease than adults. uh mortality was much lower in children and young people and keeping them away from school uh and uh imposing or not imposing but asking them to shield uh was perhaps you know again it’s that risk of a balance of risk and benefit. Okay, thank you. That that can come down now. I’m going to move on um to one more topic before the break and that is long co. Can you help us? When did um public health England become aware of the susceptibility of children and young people to long CO? So I think like uh the rest of the scientific community fairly early on around I think May May time there was uh a sense there might be be something. I mean the other thing is and it was mentioned in the previous exhibit you showed there was also an awareness of um PIMS of pediatric inflammatory um multi- system syndrome uh which also was of great concern uh but I think there was the beginning of an awareness that there may be something else as well not just in children obviously but in in adults um around long co it was very illdefined mind and uh I think continued to be so. Uh but as as the pandemic went on, I think again there’s a uh more evidence emerging about it. Do you think was there a lag between the appreciation of long co in adults as opposed to children? I’m not sure there was. I personally haven’t looked at the evidence to see whether there there was I think there’ll be naturally more of a focus on adults because adults were experiencing more severe illness generally speaking and um I think a reasonable hypo and there would have simply been more of them um and more hospitalizations and more followup. though um it may have been picked up and I think the other thing that seems to be emerging is that it it may manifest itself slightly differently in children and young people and particularly um it’s you you probably expect to see people who’ve been seriously ill or been on ITU or been in hospital might be more likely to have longerterm squeli and of course that there were much fewer children in that situation. Okay. Um, I’d like to ask you now about views expressed by a consultant pediatrician um, employed by PHE England uh, in a stakeholder meeting chaired by the Department for Education in June of 2021. If we could pull up the meet the minutes from that meeting, it’s inq00542824. So we can see the meeting took place on the 9th of June. um and that’s 2021 took place via teams. We can see the list of attendees in the stakeholder meeting. It’s hosted um by DFE but there are attendees from PHE Dr. Shamse Ladhi. He’s the consultant pediatrician. Um, and there are attendees from trade unions, local government associations, um, and and from schools as well. And if we scroll to page three of these minutes, Dr. um, Leadani says, “Long COVID could occur under a variety of scenarios.” And Dr. Dr. Ladani highlighted um the fact that any instances of fatigue or prolonged sense of feeling unwell with COVID-like symptoms in the last year would likely be blamed on CO 19. Um cases in children do not give us an indication of the general population. The pandemic has taken a huge toll on children and families irrespective of whether they have had the virus or if it is due to lockdowns or school closures. Dr. Adidani was clear that children should not be labeled with long COVID, which is a medical condition, as this has the potential to cause long-term psychological harm. It’s not entirely clear whether Dr. Leani is saying that no children should be labeled with long CO because it doesn’t exist or whether he’s saying that it’s being misreported or confused with other illnesses. But if Dr. Dr. Ladani is saying that no child should ever be labeled with long co because it’s not doesn’t exist. Is that a view which was widely held at PHE? I should also say before you answer give you time to think. Um it is not also clear that the minutes are necessarily accurate. Accurate. Yeah, that’s correct. Yes. So I I think that was my first and would I see um sorry to interrupt there. Thank you. And of course none of us were in the room. Um and um and I think I don’t think anybody at the time was denying the existence of long COVID in children. Um I think the issue that um clinicians and public health experts not just in the UK but globally were grappling with was what is this thing and how do we define it? Um because there were a long list of symptoms and particularly at the beginning at an early stage when you’ve got a complex syndrome emerging and you’re you can’t spot an obvious there’s not you know just one really specific set of symptoms. So I think uh the issue was about mislabeling um if you like and understanding making sure that you’ve got a sufficient case definition that is sufficiently specific. That also means you can advise children and parents and carers and clinicians can take appropriate action and not conflate it with other things that might require a different response. So I think that was that was the gen genuine issue that was being grappled with at the time. Um and I think it’s only fairly recently actually that WH have and the UK have come up with tighter case definitions based on um the clock study and some of the work that that the UK has done subsequently. Um so I don’t think it was an attempt in any way to dismiss or deny the existence. I think it was uh in the context of and that’s why I think the the minute may not necessarily completely reflect the complexity here um but the complexity of the issue that was being grappled with um and how how you identify exactly what this phenomenon is in a way that is appropriate and in particularly in children and young people um and then how you can respond to that. And just finally before the break, we’ve heard evidence um the inquiries heard evidence already um from an organization core participant longco kids um about the real damage that a dismissal and denial of longco and children did to families and young people. Um is it public health England’s well and now UKHSA um position that um long co and children is a pediatric illness and one that um families and and the sufferers the children themselves uh ought to have support um from the government and including UKHSA and that a denial or dismissal um is wrong. So I think as I said earlier, I I don’t think it’s ever been denied or dismissed. I think the difficulty is identifying something specifically enough that can then lead to an appropriate treatment and management pathway of support. Um and it it is now something that that element I think increasingly will sits very much with uh the NHS and with clinicians um and and requires really further research and understanding to understand what interventions and what support needs to be put in place to um really help children and young people who are suffering from some really severe and and long-standing symptoms. Okay. Thank you very much. Uh, I think now is an appropriate time for a break, my lady. It is, M. Thank you very much. You’ll probably warned that we take breaks, but I promise you we shall finish you by midday. Thank you. So, I shall return at 11:30. All right. Dr. Aurora, a last topic um from me this morning is about Public Health England’s advice provided to the Ministry of Justice concerning the detention of children in in the youth estate. A former colleague of yours uh Dr. Eman Omore was primarily responsible for this work and he provided a witness statement to the inquiry and the for the record the reference for that is INQ0649899. A criticism has been made by Offstead that PH’s guidance was not sufficiently focused on the distinct needs of children as opposed to adults who were held in the secure state. And I’d like to take you through some of the guidance now to explore that issue. Um firstly, we have a briefing which was prepared by Dr. more considering um population management in response to the COVID 19 epidemic and that briefing is from the 24th of March and it was shar relied upon as a basis for restrictions to the regime for prisoners both for adults and children and the reference for the briefing is INQ05911 and it’s summarized at the head. It says, “Prisons are high-risisk settings for large outbreaks of CO 19. Many people in prisons are in clinically vulnerable groups. The risks include excess death rates, the needs for specialist NHS care. Um, a specific objective should be to reduce as far as possible all forms of shared accommodation and single cell accommodation has distinct advantages in supporting the shielding of vulnerable prisoners. And if we scroll down the page please, Dr. Omore explains why prisons would be um more at risk of high infection rates. says um prisons concentrate individuals who are susceptible to infection um with those of a higher risk of complications. Um COVID has an increased mortality rate in older people and those with chronic diseases and multimorbidity is normative among people in prison. Um and then towards the bottom of the page that the penultimate sentence it says however HMPPS modeling undertaken with PHE has indicated the possibility of high numbers of deaths in custody and suggests in the region of 10 times the number that we would normally see two and a half to three and a half thousand based on the reasonable worst case scenario potentially half of those deaths could occur over three weeks at the height of the pandemic. And Dr. Dr. Aurora, what I want to explore with you is whether this advice is appropriate to children as opposed to adults. So would you agree with me that it is not appropriate to children because it is focused on adults in prison who might have multimorbidity who are older um and who are at higher risk of COVID of a serious health deterioration from COVID as opposed to children who don’t have those higher risks. So, I think it’s fair to say this focuses predominantly on the adult prisoner population, but it also focuses on prisons as a particular setting and the closed nature of that environment and also the particular issues of dealing with outbreaks in a closed setting. um which I think could be applicable and I think bearing in mind when this was written at the very early stages of the pandemic at that time we also didn’t really know how severe it was in children and young people versus older people. Um so and it so I think it is more focused on adults like there’s no denying that. Um and but I think it’s also worth bearing in mind that it’s not just the population, it’s the setting that contributes uh to to this and we also had at that point very limited knowledge about how COVID 19 was going to affect different age groups. Um I’m going to move on now quickly to the guidance which was in place later on in the pandemic. the 21st of July of 2021. Um, and this is the preventing and controlling outbreaks of CO 19 in prisons and places of detention. This is guidance which is issued by both the MOJ but also public health England. It’s known as the PPD guidance. Um so this is quite a late iteration on um more than a year from the onset of the pandemic and we can see um we don’t need to move to it but on page three it it clarifies that it applies to young offender institutions secure training centers and secure children’s homes and on page thank you so quick on page 10 it says that uh all new and transferred prisoners or detainees should be isolated in a reverse pardon me reverse cohorting unit for up to 14 days and tested for uh co 19 and it’s clear that um we don’t need to go to it but on page 12 it makes clear that that those arrangements applied equally to young offenders institutions and secure training centers. And this reverse cohorting meant in practice that children held in young offenders institutions and secure training centers when they returned to the prison from a court appointment for example or when they entered the prison for the first time or if they were transferred there that they would be held separately um from other prisoners for 14 days. And in some cases, as we’ll hear this afternoon, um were not able to leave their cells um sometimes for days at a time, sometimes for only half an hour. And what I want to ask is this is some 15 months into the pandemic. By this stage, there were few restrictions in the community and children, even clinically vulnerable children, had returned to school almost a year before. Was it appropriate at that stage to have this le level of severe restriction on children in custody bearing in mind it was known by that point that the risks to their health were very low. So I can understand why basic infection prevention control principles would still want to apply and there were still outbreaks occurring in adult prisons. Um I think there there was some associated more operational guidance uh that was provided I think by the youth offending service and NHS England to try and uh make it more specific to the settings where children and young people were being held. I think it’s fair to say this this is very focused on managing um CO 19 that was still quite a serious issue in prisons at the time for adults. Uh if I could just pause you there there was specific guidance but this the PPD guidance continued to apply. Yeah. And while there were still outbreaks in adult prisons this guidance applied to young offenders institutions and secure training centers. So there could have been separate PPD guidance for for children, but there wasn’t. And my question is whether this guidance was appropriate to be applied in institutions that held children. Again, I think it’s quite difficult to comment and I think um you’d probably have to ask Dr. Omore as as to the rationale as to why. Um I think one of my reflections is um if I go back precoid um children and young people’s uh secure estate was always included in um how uh in the multi- agency approach to outbreak management and I I think there’s there was probably been a a bit of a continuation of that’s what we did before so we’ll carry on doing that. CO was obviously different from you know outbreaks do happen but they’re usually more limited um and I think one of the learning that we’ve really taken away from this is that we need to understand more about the diversity both of the population and the nature of the settings within the children and young people secure estate and the reasons why children are there. So I think um the offstead uh points were actually have been helpful to us in creating a slightly different paradigm about how we go forward. Okay. Well, just before we end then I’ll just show you the Offstead criticism as it set out. So you can tell us if there’s anything you don’t agree with. That is INQ0588111 um paragraphs 722 of the statement and 724 says, “One of the most significant problems faced by young offenders institutions and children’s homes and training centers was that public health guidance was focused on adult settings rather than children. This was regularly raised in joint partnership meetings. Um the response was not consistent and the guidance contained many mixed messages. It exhibited a lack of understanding of the operation and needs of children secure settings and I think you would agree with that. You said that was a learning point for you that it was necessary to have that greater understanding. If we can just scroll down, pardon me, to page is that it is. So you asked me if I disagree with this particular statement and I I I do it’s slightly more nuanced than that. Um if you don’t mind putting it. Yes, let’s go back. So um I think uh the the joint partnership is really important and it’s something that um we try and work with our partners because what we are experts at in public health England and UKHSA is um infectious disease and environmental threats and how they might play out at general population level. We do rely on working really closely with other government departments and sector specialists who understand how to operationalize good infection control um and prevention evidence into their setting and we cannot possibly understand all the nuances and how things are working and the partnership is between NHS England PH at the time now AXA Mojmpps and DF Um, so I think I think there’s a question here about what guidance can really achieve and then how we need to work uh with other government departments nationally but also locally um every uh uh public sector organiz well a whole range of organizations have access to our regional health protection teams who will give specific advice based on uh anything going on at the time. So I think I I I can see I def as I said I think it it has made us really sit back and think about this but I think it’s it’s partly how we work in partnership and get the right uh information and intelligence and work together to make sure that we have guidance that both really does do what it’s there to do and protect people um from infectious disease but also we’re making appropriate um interventions to to balance any risks that implementation might produce. And although um this is an account of uh of issues being raised with PHE um from our records, I’ve not really been able to find an audit trail. So, it’s a little bit difficult for me to particularly answer that one one way or another. Um, but I appreciate things were moving fast and rapidly, but I know the health and justice team were present at a lot of outbreak meetings and really keen to work in partnership. I see. Um, thank you very much, uh, Dr. Aurora. That’s the end of my questions for you. There are some additional questions for you from, uh, some core participants. There are, Mr. Anga goes first and she’s just there. Dr. for Aurora. I ask questions on behalf of Longco Kids and Longco Kids Scotland. I have some short questions on PhD and’s response to Longco. You told us this morning that PHE along with the rest of the scientific community became aware of longco in children from May 2020 and of course you’ve explained that PHE provided scientific advice to DOV. When did PHE share that understanding with DOV? I’m afraid I’ I’d have to go back and and look at the the detailed timeline for that. Um would you be able to give us a sort of time period whether that was in late 2020 or whether it was at some point in 2021? I asked because your statement doesn’t touch on longcoid. So we’re trying to fill some uh some knowledge holes if I might put it that way. Um I would re partly as I say because I’m I’m relying on uh sort of the evidence and paper trail myself. I I would struggle to kind of uh answer that without being able to factually check that. Um but so if we could speak in broader terms in that sense the inquiries heard evidence of teachers frequently dismissing pupil symptoms, pupil’s longco symptoms out of a lack of understanding of the disease, not knowing that the disease existed. Would you agree that teachers, parents, and schools would be helped by timely basic information that longco exists in children that it causes debilitating disabling symptoms and that that inevitably has an impact on educational attainment and educational attendance? And I think that was certainly an issue in 2021, wasn’t it, about what information should be provided and could be provided. Um I think again it I’m always in favor of sharing as much as we know about something um with the public even if it’s to say this is what we don’t know as well. Um but I think they are they it was clearly a complex area throughout 2020 2020 was just beginning to emerge but 2021 um even then I think there were a lot of complexities around it. Um but I do as a principle think that it is always good to share as much as you possibly can with professionals and the and the public. Um you said it’s a complex area but but the question is really a very simple one on whether the existence of longco something that PH was aware of from May 2020 should have been shared in a timely way with teachers and schools so that that dismissal of pupils didn’t endure so they pupils could access education. Would you agree with that principle? I think there was general understanding again across DHSC CMOs um and uh widely that that long co was a phenomenon but I think it’s the level of detail of what we understand about it how you diagnose it uh specifically enough and what you should what you can then respond to and do about that. I I think for me there’s something about any child or young person who was experiencing difficulties in being at school or returning to school whether it’s long COVID or anything else needs to be supported appropriately but I think there was some understanding of the possibilities of long co at the time but even in PH we didn’t have we have been aware of it but we really do did not have a very good understanding of it even in 2021 and Even today, I think it’s still a complex area to define, diagnose, and then decide what you need to do about it, but um certainly I think there was awareness at the time that it it could be an explanation. You said that it’s a complex area and more needs to be done. What is AXA doing to build that evidence base on pediatric longco now 5 years after the onset of the virus? So um Axa at this stage I think a lot of this now is about understanding the more clinical nature of the illness and also what interventions can be put in place to assist recovery to help identify whether there’s a a groups of children, young people who may be more prone to longer time periods of suffering. And a lot of that is now much more in the realm of what I would call more clinical research and academic research. And with with the NHS, we’re obviously keen to continue as an organization to review the evidence. Um we supported WH in helping to come up with a case definition because you need a case definition to do research as well. Um which which we now have. But is Oxford currently doing anything on pediatric longco? So aside from the clinicians, aside from NHSSE, um not I would need to go back and confirm that, but I’m not aware that we’re doing any active research, but we will be reviewing the evidence base regularly because obviously it is part of our understanding of uh the longerterm consequences of COVID and its impact on population health. And my my final question which is one that looks forward you’ve said in your witness statement that it’s critical to have good data to inform advice to have evidence-based data um uh to develop guidance and effective systems of surveillance. The UK in relation to pediatric longco is is flying blind in relation to the surveillance and monitoring of longco in children young people. There’s no national monitoring of prevalence or the impact. Would you agree that it would be helpful if DOV required schools to use specific codes to monitor longcoid absences that that might assist policym for example? I good data collection and granular data collection is always helpful. Um so I think it’s an area to explore but also again through the NHS now that we have a case definition and and codes I think quite often a lot of research will be based on uh what’s picked up both through primary care and uh hospital coding as well. Dr. Thank you. Thank you my lady. Thank you uh Miss Peacock who’s done the end there. Thank you my lady. Good morning. I ask questions on behalf of the trades union congress. The topic is air filtration devices in schools, which you’ve already addressed to some extent in your evidence. Taking into account the lack of mechanical ventilation in many school buildings, and the practical difficulties faced by schools in terms of improving manual ventilation such as windows which do not open, thermal uh comfort issues. Did the provision of air cleaning devices in schools mainly taking place in 2022 and 2023 come too late? So again, um this links back to our understanding of the evidence base and uh understanding how effective air cleaning devices could be in those settings, what what the constraints might be, whether some devices were better than others, how many devices you might need in a given classroom, and any consequences of those devices that might also adversely impact such as noise or safety issues with young children around. So, um I think what we’ve what we’ve tried to present is that the evidence through the pandemic um has provided us with an opportunity to to improve the evidence base. Um but certainly it’s something and so it’s something that we can certainly build on for the future. on that point and just by way of followup, your statement says that since ventilation and filtration are generally accepted to be effective interventions to reduce the transmission of respiratory infections in all indoor spaces, this evidence is equally relevant to school settings. And just for the record, that’s at paragraph 5.16. On reflection, couldn’t the guidance have reflected that point of general principle from an earlier stage in the pandemic given it was a novel pandemic quickly evolving and perfect evidence on interventions in schools as you’ve outlined today is very difficult if not impossible to obtain. So I I think this links back to what was understood and and the approach um taken at the start of the pandemic when very little was known about um SARS KV2 and uh the earlier hypothesis about mo method of spread if you like was more around droplets and fomite spread and it was only as I think it it became obvious that um aerosol had a bigger role than had first been identified. Uh that um the issues around ventilation then became more salient given though that aerosol transmission was recognized uh perhaps in in 2020. Was not that then lag in uh these devices not reaching schools until 2022 and 2023 not quite significant? I mean again we don’t have a hugely strong evidence base for saying you know this is absolutely going to make a huge impact and we need to do this really early and it’s going going to make a big difference to the risk here. So I think there’s also some logistics and and that logistics and and operational side is is not really um for user to to comment on but um clearly I think for me it’s more about what we do to make all our public buildings and and schools sort of more resilient to uh sort of external threats whether that’s infectious disease or uh climate change challenges. I think that’s my time. Thank you. Thank you, Mr. Pop. Um, Douglas, who’s just there? I’m afraid to say it’s me. Oh, Mr. Wagner, I’m so sorry. No, no, it’s fine. It’s just disappointment for everyone. Um, good good morning. Um, my name’s Adam Wagner and I act on behalf of clinically vulnerable families. Um, I want to ask you, um, first, Dr. Aurora about the DFE’s system of controls um which you refer to in your statement. I want to ask you about the first the sorry the guidance in July 2020. Um it it’s a INQ 0000648028 please. Now you you just referred to it with with with Miss Peacock and you said earlier in your evidence that if you go back to the start of the pandemic, what we knew about the virus at the time, there was a stronger focus on droplet spread and less so on air um aerosol spread and therefore a strong focus on the measures that you would normally apply in that case. Um ju just going to page six of this document please. I’m sorry, page five. And and you can see there if we can just um get that box at the on the second half of the page that says system of controls. Um I’m sure you’re familiar with these, but you can see there these are the prevention actions which the school must take. So the the mandatory actions says there minimize contact with individuals who are unwell. Clean hands thoroughly. Ensure good respiratory hygiene and promoting catch it bin at killer approach. Introduce enhanced cleaning including cleaning frequently. Touch surfaces often using standard products such as detergents and bleach. Minimize contact between individuals. Maintain social distancing and where necessary wear appropriate PPE. So those are the mand mandatory controls. Would you accept that in July 2020 those that that system of controls was unlikely to be have significant effect against an airborne virus like CO 19. So obviously at the time that was based on the evidence available at the time. Some of that would have had some impact on an airborne virus. And I I wouldn’t say we wouldn’t do any of those even if it was an airborne virus. In fact, we we would do them as well as part of that package of interventions, but they wouldn’t be what those measures aren’t the measures you would prescribe for an air if you had thought the virus was air airborne. You would have other measures as well. I think um I think quite Yes. And I think that that appeared in in as the guidance evolved when we saw um different measures being promoted and and brought into guidance. Yeah. But but looking back in and and and in retrospect those measures were insufficient for an airborne virus. I think they weren’t completely effective, but I think it’s always going to be hard to be completely effective. But yes, there I think there there could be other measures under consideration if you if your primary focus is aerosol. Sorry, obviously it’s always going to be hard to be completely effective, but isn’t that a bit of a copout? Isn’t isn’t it the reality that if you had known if we had known there was an airborne virus, those measures definitely wouldn’t have been sufficient to control it. I think um if we had known we obviously would have uh been thinking about what else we knew about transmission and there was a lot of work going on at the time to try and establish um how it did spread um to to see what else we should be considering. I want to ask you now please about um reopening schools in March 2021. Um and at paragraph 3.72 of your statement, you summarized the analysis that supported those that reopening and that included testing and isolation measures implemented to detect COVID positive students and at that point the isolation period for children was reduced to 3 days. Um do you agree that by reducing that isolation period as well as restricting testing unless advised by a health care professional that meant infectious children were likely to be returning to classrooms? Um I think by then we also knew much more about the infectious period um and viral shedding and um so again I think it’s a judgment here about balance of risk versus benefit and minimizing school absence whilst at the same time taking adequate precautions that reduce the level of risk of further infections and transmission. So again, that would have been based on the best evidence available at the time. Well, I mean, it’s always going to balancing risk is always important, but don’t you agree that by reducing the period to 3 days and reducing the the need for testing, you’re going to be making it more likely that infectious children are going to be in the classrooms. I think the other thing to bear in mind is there was the higher levels of population immunity. um we were beginning the vaccines program as well. So I think there are other factors that would have influenced why it felt reasonable to move to um a less burdensome testing regime and reducing uh the period for isolation. So sorry I if I wasn’t clear that wasn’t the question I asked. They asked, “Do you agree that that reduction in time period and the reduction in testing would make it more likely infectious children would be in the classroom?” Um, I mean, I can’t really comment on that because I haven’t seen the the detailed data and evidence that led to that conclusion, but the process would have been that that would have been based on the data and evidence available at the time and gone through uh proper processes and scrutiny. and was any assessment made of the disproportionate impact that that shortened isolation period and restricted testing would have on clinically vulnerable children and children who had clinically vulnerable family members. Um I’m not aware of any specific assessment made. If anything had been picked up for example through uh presentations at hospital I think um that would have been detected through data um and concerns provided through the NHS. Thank you Dr. Aurora. Thank you Mr. Wagner. Um I’ve just checked that completes um the questions for you today and also the demands that the inquiries been making upon the UK HSA. Um please thank you personally for what you’ve done to try and help us today. U but thank your colleagues too for all the help they provided over the course of the inquiry. Thank you. Thank you. Right. Is it Mr. arena. My lady, may I please call Miss Caroline Willow. Thank you. Just like to repeat after me, please. I do solemnly, sincerely, and truly I do solemnly, sincerely, and truly declare and affirm declare and affirm that the evidence I shall give that the evidence I shall give shall be the truth shall be the truth the whole truth the whole truth and nothing but the truth. and nothing but the truth. Thank you for taking hope. We haven’t kept you waiting. I think you’ve been following proceedings anyway. Thank you, Miss Willow. You have provided a witness statement to this inquiry dated the 11th of August, 2025, and the reference we have for that is INQ0000588071. Can you confirm please that the contents of that statement are true to the best of your knowledge and belief? That’s correct. Miss Widow to to start with article 39 and your professional background. You explain in your witness statement that article 39 is a small independent charity which which fights for the rights of children living in state and privately run institutions in England. You founded Article 39 in 2015 and served as its director from that time up until 2024. Um, however, prior to founding article 39, you had a career in social work which started in 1988. Is that correct? That’s correct. And you became a children’s rights officer for children in care and carelevers in the early 1990s. And you’ve held specialist posts at the National Children’s Bureau and you led the Child’s Rights Alliance for England between 20 and 2012. And finally, in addition to that experience, you’ve served on many different advisory groups that had a specific focus on children and their care. Would that be a fair reflection of your experience? That’s fair. And Miss W, can you help us with with how you define um state and privately run institutions? What what type of institutions would that include? They are institutions where children live in group based settings. So they’re not in a family environment. They include children’s homes, supported accommodation for children in care age 16 and 17, mental health units, and prisons. And Miss Willow, prior to the pandemic, just to touch upon the day-to-day and the practical workings of article 39, um it’s right, isn’t it, that uh article 39 would raise awareness of the rights, the views, and the experiences of children. You would provide legal education and tailored advice to independent advocates for children and young people. you would run national campaigns and you where you deem necessary would pursue strategic litigation that would challenge um what you would define as serious and or systematic children’s right breaches. Is is that correct? That’s correct. Did did the pandemic have any impact on the delivery or the focus of article 39’s work? We continued all of that work. And if I may say that the name of the charity comes from article 39 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which grants children who have been abused, chronically neglected or exploited or suffered other rights violations the right to recover in environments where their health, self-respect and dignity are nurtured. And that’s a really important starting point uh for the charity because the whole ethos of the charity is children’s recovery, children being known, understood, their perspective, their perception of their needs and what will make life better for them must prevail. And you say, Miss Willow, in your statement that article 39 has a rare insight into the challenges facing looked after children across the country as communicated by them. Can you help us with how practically that information gets from them to you taking into consider taking into consideration many of these children live in secure institutions. So a core part of the charity as you’ve said is um emboldening informing equipping independent advocates who stand right next to the child whether they live in a children’s home a prison or mental health impatient unit to understand to know and to be able to apply the law and the rights of that child in that given situation. And the uniqueness of independent advocates is that they are there for the child and no one else. Um, we were called children’s rights officers back in the day, which is how I got into children’s rights. And all of our work with advocates is working on what children and young people have brought and and expressed and shared with their advocates. So we have a direct route um about the concerns and the experiences and views of children. Miss will that include independent advocates going into secure institutions speaking to children maybe over the phone or would it be a a variety of different ways you would actually communicate with those children? Yes, it does. Um being a small children’s rights charity and very visibly there for children also means that we regularly hear from parents, from carers, from loved ones including of children in prison um who tell us what life is like for children. And we also run uh groups and activities and events for children and young people. Miss Will, the inquiry has heard evidence from Mr. Charlie Taylor, his majesty’s chief inspector of prisons for England and Wales uh and how um the inspector gains that information from a different perspective. Um he summarized that at times children were spending up to 23 and a half hours in their cells. Face-to-face education stopped and was replaced with worksheets and work packs and prison visits were suspended, meaning that children were going many months without face-toface contact with their families and friends. Were these findings consistent with what you were hearing on the ground from parents, carers, and from the children inside these institutions? absolutely consistent and the description of the injury, the psychological and emotional injury uh to children um is also what we were hearing and aware of. And of course, when you’ve been in social work and children’s rights for an awful long time, um, previous research, investigations, inquiries, proclamations as to how things will be different for children in the future, they’re always there. They’re always in your head whenever you read or hear from uh, children, read about children, or hear directly from them. Miss Willow, um, on the topic of oversight, you’ve mentioned how you have an independent children’s advocate network. We’ve the quir the inquiries heard evidence from Mr. Charlie Taylor. You explained in your witness statement that article 39 feared the loss of external oversight for children. Um, the inquiry knows that his majesty’s inspectorate of prison suspended inspections of young offender institutions on the 17th of March 2020 and introduced short scrutiny visits from April 2020. And in a similar fashion, Offstead um who inspect or who lead inspections of secure training centers also suspended inspections in March 2020 um but didn’t introduce assurance visits until September 2020. Um the inquiry heard evidence that the the main reason for that was on the back of public health advice. And of course there’s a balance between inspectors getting into prisons but inspectors trying to stop bringing COVID 19 into prisons where children are. So so in one sight it could be counterproductive. Um where does that balance lie and is there any solution as to how in the event of a future pandemic the inspectorates can function whilst maintaining the safety of children in prison and complying with future public health advice. The public health advice needs to take the whole child needs to take in their physical, their psychological, their emotional health and to seriously consider the impact of advice and decision making on children as whole people. And the literature, the body of knowledge that is known about the risks for children of closed institutions goes all the way, my knowledge of inquiries goes all the way back to the 1960s. And as well, I’m sorry to pose you there. I think we I think the point you’re making is that independent inspections are still needed in the event of a pandemic. Can you help us with practically if if inspectorates can’t get into the particular institutions h how can people achieve that level of oversight? Well, one aspect of the prisons inspectorate process is surveys of children um which they have been doing for over 20 years. So of course that can continue um to be able to have when they are prevented due to um lack of knowledge the initial weeks of panic and and and having to to work out um responding to the virus. they can um connect into the prisons through uh remote means and also critically to have contact with children’s loved ones because children’s loved ones, parents, carers and others that are um by the child will know about the child, the individual child. they will know what they were already suffering and dealing with before and they would be able to pass that uh to the inspectors. However, it has to be an imperative that the inspectors get in there and that has to be the headline task for those given advice to government because of the knowledge of the risk of closed institutions developing punitive coercive cultures. Um there is decades of evidence of the risk and the injury caused to children when there isn’t an external oversight. And it’s not just that an external oversight exists. It’s also that it is seen to exist. I as well just just so I’m clear before we move on to the next topic. Is your evidence that the balance between managing the risk of potentially bringing the virus into the prisons but then not inspectors not getting into the prisons because of the potential risk of regimes and what what’s happening. Is your evidence that balance would fall in favor of inspe inspectors getting into prisons? Absolutely. Children have taken their own lives because of abuse in prisons. Children have suffered horrendously from self harm because of abuse in prisons. And that information is known and that has to be part of the reckoning as to what are we going to do in this scenario to make sure that we can do our absolute best to prevent uh harms to children. Um, Miss Willow, remaining in the the pandemic times of the the prison system and the youth um, justice system, I want to now ask you about the process by which the changes were made to the regimes. Um, the the inquiry has also heard evidence that the temporary regime restrictions were applied across the adult and the youth estate from the 24th of March 2020. Um, but we then know that amendments were made in May and July of that year to the prison and young offender institution rules 2000 and the secure training center rules 1998. And the purpose of that was to reflect in legislation the current operational situation of the temporary restricted regime that had already been implemented as we know within the different children’s prisons. And and I want to ask you about your views as to the process those changes were made because you explained in your statement that in July 2020, Article 39 made a freedom of information request for the child rights and equality impact assessments undertaken before the government made the amendments. Um Could you outline your headline concerns as to as to why you wanted that and why you felt it was important? These were very substantial and serious changes to legal protections for extremely vulnerable children. Over half of children who were in prison and were in prison at March 2020 uh had been in care. A third were disabled and many had health conditions and needs um that required uh the the best of protection and care during the pandemic. So the context is that these are highly vulnerable children. If you are going to take away legal protections that are there because we know children um can just about survive prison um by seeing their mom or their grandma or their dad. that children can just about uh survive prison by having something to do and not being stuck in a cell the size of a small bathroom for 20 22 23 hours a day. Then if you are going to take that away then you have to follow a robust rigorous process. Otherwise all the child protection legislation we have in place all of the procedures all of these systems we have in place count for very little and that freedom of information request was systematically going through. Did you seek advice from the children’s commissioner? Did you carry out a children’s rights impact assessment? Did you inform children? Did you inform their parents and loved ones and so on? Um, and that was to hold the Ministry of Justice to account. This is what you are meant to be doing. if what you say in paper and there’s an awful lot of paper surrounding child prisons uh is correct and is to believe to be believed. Um, Miss Will, I I was going to move on to ask you a question that what the Ministry of Justice or the government may say is that given the situation they found themselves to be in, which we’ll hear more about this afternoon, that irrespective of a child rights impact assessment, the amendments would have needed to change in any event. Um, and I was going to ask you, well, what purpose would the child rights impact assessment have served? But is your evidence that it was simply hold the government to account to make sure that they were considering impact much more than that. C could you expand on that please? If those processes had been followed, hopefully they would get uh a series of responses which in Technicol remind them that these are highly vulnerable children and you cannot amend the law which will legitimize uh treatment and arrangements that will cause great injury, psychological, emotional, physical injury to children. Um, Miss and I want to move on to government understanding and if we can have on screen please InQ0000588042. Um, this is a witness statement from Lucy Fraser King’s Council the former Minister of State for Justice responsible for prisons and probation. We can see at paragraph 271 that the statement says as throughout the pandemic operational decisions were taken which considered the needs of children and the particular impact of restrictions on them. Did you feel from what you know and what you were hearing on the ground that the government did in fact give sufficient consideration and weight to children’s rights in decision-m during the pandemic? There was no evidence of that. And if if we focus specifically on the pandemic um and what was happening in prisons during the pandemic, what was Article 39 doing to try to help to promote and protect the rights of children? You you’ve given us one example where you were writing to the Ministry of Justice asking for um impact assessments. Was was there anything else you you were doing with government to say this this has to change? We coordinated a joint letter uh which was sent to government on the 18th of March 2020 to call for uh children who could be safely re released into the community for that to happen. Well, just on that point, I think it’s right, isn’t it, that um whilst that process would have started in March during the pandemic, uh and I’ll be corrected if I’m wrong, that actually no children were released under the early release provisions. Uh can can you just pro provide us with your opinion as to why that might have been the case when we know many many adults were released? Uh that’s correct. Um fundamentally I think it comes down to the low status and the low priority given to children. Um the narrative that children were not at risk of dying from the virus. um rather than looking at the whole child and and what the virus could do to them in terms of how prisons would uh then um make children uh spend prolonged periods in their cells uh stop education, stop the family contact. So there wasn’t a full um understanding of of children and their needs and the calls for the safe release of children uh continued throughout including from many other organizations and bodies. Um, I have to say that having reviewed evidence and and disclosure that I I hadn’t previously seen, uh, to read, for example, that children who, uh, didn’t have a home, children who were in care couldn’t be released to a bed and breakfast or released to homelessness. Um, well, that’s not good enough. if there are children in care, they should have homes to go to. Miss, well, we’re going to cover that topic later this afternoon. But just on the point of um the government understanding the needs of children, if we can turn please to um His Majesty’s prison and probation service operational guidance. Um we know that following the rest restrictions on the 24th of March 2020 that around 3 weeks later the Ministry of Justice and HMPPS issued as we can see on screen amended guidance dated the 15th of April 2020. Um and this guidance set out how prisons would ensure that inmates had access to the essential services including meals, showers, telephone contact with loved ones, uh access to legal advisers and access to health services. Um this is a 42page document that we we’ve simply not got time to go through uh today. Um but we know that that there’s around two pages that are dedicated specifically to the youth custody estate. And if we can move please to the second document INQ 0000575485. Um we can see that this is another piece of key guidance. Uh this time the coid9 national framework for prisons and regimes published in June 2020. And it’s correct, isn’t it, that it was this document that provided a conditional roadmap to how prisons would ease out of the restrictions. Um, and some may suggest that this document also provides limited reference to children on the children’s secure estate. Um, but to be fair and to be clear that this isn’t all of the guidance, but if I understand it right, you you did read the guidance at the time and you you read it subsequently, correct? Um it’s been suggested Miss Willow and we’ve we’ve heard the off offcom criticism sorry the offstead criticism about the guidance um this morning. Uh but in your overall view, did the guidance issued during the pandemic by HMPPS or the Ministry of Justice recognize and promote the distinct needs of children or was it the case as suggested by others adult guidance was simply shoehorned into the EU state? The guidance is completely inadequate uh for children. So the answer is no. Children uh are invisible in these documents apart from the words youth custody service and and children. There’s no tangible practical stand alone. And why are children in the same documents in any case when there is meant to be a separate secure estate for children? Miss if we can now turn to secure children’s homes please. Uh if we can have on screen INQ 000000588111 um we can see paragraph 724. This is a witness statement from Mr. Matthew Coffee provided on behalf of Offstead. Um and we can see in his statement that he says that children in secure children’s homes received a much better offer. Although the initial period of lockdown was crisis management, in a very short time, secure children’s homes generally got to grips with the restriction requirements. They applied a child center approach, resulting in children for the most part having a normal routine, including attending education. Is this something that article 39 recognized during the pandemic from speaking to children? Absolutely. Secure children’s homes are part of local authority children’s services. They follow the same law, standards, regulations as children’s homes in the community. They are child uh establishments. They are staffed by multiddisciplinary teams that are there for children. They are in every respect possible different from prisons. And just because we say child prisons because it has child in front of it, make no mistake, uh child prisons are prisons. They are uh adapted in some ways, but fundamentally the child’s experience is the same as uh an adult experience. Um as well if we could now turn to um residential children’s home generally um can you help us please with how many people in March 20 sorry how many children in March 2020 were living in children’s homes just under 7,000 children and we we will return to residential children’s homes but I want now to to move on to the amendments to social care regulations to to ask about the context behind those before we we return to the particular impact those amendments had on residential children’s homes. Um we know that one of the main changes to the provision of social care was introduced via the adoption and children coronavirus amendment regulations 2020. Um at a very high level c can you please just explain what what the government was proposing to change in March and April 2020? Well, in April 2020, it actually did change radically change the children’s statutory scheme. Um, so overnight between the 23rd and the 24th of April 2020, over a 100 changes were made to 10 separate statutory instruments. And of those over 100 changes, uh, 65 safeguards for children were deleted or diluted. Did any of the changes increase legal protections or was it simply they were they were diluted? There was not a single increase. And if I may um, share some examples of the changes, the deletions and the dilutions. M miss we’re going to come back on to the specifics but I just want to ask you before we get there please that the inquiry heard from Baroness and Longfield as you know the former children’s commissioner for England and she described feeling horrified about the changes when she found out about them on the 16th of April 2020 and the inquiries already heard about the consultation and the background to that with Baroness Longfield but I want to ask when you first became aware of the proposed changes. I became aware when they were published and somebody emailed me. We were expecting a statutory instrument relating to children’s homes. We were not expecting what was published. And so then I sat at my desk for several hours until after 10 p.m. that evening working out exactly what this statutory instrument did and took away from children. What was your understanding as to as to to why the government was seeking those changes which we know changes were? The explanatory memorandum which was published at the same time um depicted these changes as changes to administrative burdens to procedural matters and that this was to ensure that children’s social care could continue to operate so that core safeguarding could continue to operate. Now that was a fallacy because the changes that were included in the statutory instrument included core substantial safeguards for children. They they are and were safeguard duties. So for example, social worker visits. I started my career as a local authority social worker visiting children in care. I know how critical they are uh to children’s protection, well-being, sense of belonging and being wanted and also what you can see when you go and visit the child. Now, not only did the regulations uh define a visit as having a phone call or a video call, it also took away the very clear statutory requirement to visit a child at minimum every six weeks. Um, so here we had the Department for Education saying children in care, the most vulnerable children in society, local authorities, you do not have to even call them once every six weeks because that was taken away from the statutory scheme. Another example, the temporary approval of what was in law before of connected people uh to children in care. So that would be say a teacher or a grandma or an auntie or uncle. There was provision already in the law that a full assessment of those people didn’t have to happen. um for 16 weeks. If um the local authority was satisfied that broadly speaking, it was suitable for connected people. It’s obvious why it would be ch uh people that the child already knew that already knew the child. So another of the changes was to extend that to 24 weeks and to say the connected person aspect does not apply. So this can be anyone and there was already provision in the law to uh for a nominated officer to increase that to another 8 weeks. So here you had 32 weeks where a child could be placed with somebody that doesn’t know them, that they don’t know for 32 weeks. And another removal was to dispense with the uh nominated officer’s approval if a child was sent out of their area. Now all of these safeguards are in law because things have gone wrong and things are known to have gone wrong for children. That is why um the out of area approval for example because social work knows that children who are sent out of area are much more vulnerable than children who are in their local authority. Miss Ju just on that point um the inquiry heard um that Baroness Longfield concluded in her evidence that there wasn’t an understanding about the level of risk to some children some children were living with dayto-day in your view was there a disconnect between policy makers and what was actually happening on the ground I don’t believe they had any understanding um and actually the court of appeal and the high court uh share that maybe not in the the the same short assessment that I’m given um as to the magnitude of the statutory scheme taken together and the individual safeguards. Remember the characterization of these individual safeguards and what the minister Vicky Ford was told in her briefing is that these are minor burdens procedural. Now if you are a minister who’s been imposed for about a month and you get a briefing from civil servants that tell you these are minor these are burdens these are procedural and minister we have to do this in order to save children’s social care generally then unless you come with a whole load of experience of children in care with a professional background then you’re likely to give your approval which of course she Miss, can you can you help help us with with this please? We know the amendment regulations came into force on the 24th of April 2020. Um were they timelmited until the 25th of September 2020? They they that was what the statutory instrument said, but there had been government statements elsewhere that um they may be used as a uh testing ground to see whether these minor burdens could be done without in the longer term. Also, it was tied to the Corona virus act. So it was very probable from our perspective and many other um children’s rights advocates that these uh changes could continue in the longer term. And we know that article 39 um started legal proceedings to challenge the amendment regulations soon after they came into force. Um, did you bring your concerns to the attention of the government before the legal action? Well, the pre-action protocol sets that out. Of course, uh, the letter that goes to government. Um the uh on the day the statutory instrument was published, um our website set out in detail that evening the consequences for children of this statutory the change to the statutory scheme and we also uh made any noise we could in the media. Um article 39 is a charity that is known by the department for education. um they watch and would have been well aware even before that pre-action protocol letter and it was published in the sector press also and there was lots of social media coverage including of course uh from the association of directors of children’s services local government association the network of principal social workers who uh confirmed uh that They were not aware of the full magnitude of what the Department for Education had pushed through. Miss Willow, we know that the government’s position certainly at that time was that the changes were needed because as you’ve already alluded to um they were described as administrative burdens and minor changes and you’ve also alluded to the fact of fears of staffing issues and that the danger of the pandemic would have led if the changes weren’t made to children and their care almost being nonexistent. Is it your evidence that in terms of the government’s bal balancing act between uh staffing issues and risk, the issue was that the government didn’t actually or properly understand the risk and the practical consequences of what the amendments were about to achieve? They didn’t properly understand what they were doing. This also came after several years of other attempts by government including through legislation uh to uh relax inverted commas uh safeguards and to give local authorities more flexibility inverted commas. Um so they didn’t understand these safeguards. They were in a mindset of deregulation that local authorities are overburdened. Their words not mine. Uh overburdened with duties towards highly vulnerable children and they needed to have leeway and and freedom uh to to uh change their practice. So that was precoid. Um from my perspective that mindset uh carried over to the COVID times had there been a real understanding as to the importance of social worker visits as to the importance of statutory re reviews of children in care as to the importance of having oversight when children are put into babies largely put into foster and for adoption placements as to the importance of having an independent monthly check in children’s homes. Had they understood all of that and actually if they didn’t understand any of that then they could have come to children’s rights organizations uh who stand next to children and ask us. M Miss Willow, I need to just cover two topics very quickly if I may please because we’re about to run out of time. But in terms of whether the changes were used um a statement has been provided by or on behalf of the department for education by Miss Francis Orum and to summarize what it says in those statements we can see at paragraph 21 that the DFE has not subsequently specifically or distinctly measured the impact if any of the regulations of any of the regulations partly because reported use of the expect except exceptions sorry was And at paragraph 4.9 again it re reiterates the point that after gathering regular feedback from a variety of sources including local authorities, social workers, charities, offstead and other key partners um that the engagement with those stakeholders indicated that the amendments had not been widely used overall. Um ju just very briefly was that your view? Who knows? The statutory instrument itself placed a statutory duty on the secretary of state for education to review the effectiveness of the regulations. uh as far as I can see uh from what has been published and released by the department for education that the one-sided consultation that happened in the um producing the statutory instrument continued um when they were uh seeking information as to their implementation and there is a fundamental fallacy at play if you look at some of the documentation from the department for education when they were sending out surveys to local authorities or ringing up uh their contacts in local authorities. Are you using the flexibilities, so-called flexibilities? Well, we did only have um one version of the statutory instruments from the 24th of April 2020. It wasn’t that all of the 10 statutory instruments that were previously in law uh were still there and then we had all these amendments. The statutory instrument had fundamentally changed the statutory scheme for children. So asking local authorities, are you still with the old law? Um bet betrays a a lack of understanding. And of course, it’s self it’s self-reporting. This is requiring expectant local authorities to report to central government that yes, we we’ve stopped having six weekly telephone contacts with children in care. We’ve stopped reviewing their uh welfare. We’ve let uh people who are not connected to children um look after them without a full assessment. Uh we’ve stopped placement plans uh which were very clear in law before. You are expecting local authority to say we’ve done that and and could you tell the minister that um this is the effect on children and of course they were never asked actually the the effect and impact on children. They were just asked are you using the flexibilities or not? Miss Willow, final question. Having time to reflect on what happened during the pandemic, what can be done to better protect the rights of children living in institutions and being part of decision- making in the event of a future pandemic. Could you maybe s simplify, clarify or provide us with your headline points? Two headline points. Firstly, we need a cabinet minister for children. Uh a cabinet minister who has the status and the department that is taken seriously across government and which is the overall uh cabinet position for matters relating to children. And secondly, um, in order to make sure that children are not put to the side, in order to make sure their needs, their perspectives, their rights are properly considered at all levels of government and are taken seriously, we need the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child to be made part fully part of our domestic public law. And that is because we need a fundamental cultural shift across government, but also children need the backup, the legal backup of having enforcable rights and entitlements that cannot be just removed at a whim. And if I may add a third uh a statutory duty on government departments to consult and then to give weight to the statutory children’s rights body which is the children’s commissioner for England. M Miss Willow, thank you for that. My lady, those are my questions. Do you have any questions? No, I don’t. Thank you very much indeed. I’m very grateful to you. Um you’re a very passionate and effective advocate. I think you’re trying to do Mr. Troy out of a job. Um but and I see you were called to the bar as well so he better watch his step. Anyway, thank you very much indeed for the help you’ve given and for the participation that you um article 39 have had in the inquiry. Thank you. Very well. I should return at quart to two. All right.