Genetic mutations aren’t as scary as they sound. With RNA viruses, like the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19, they’re happening constantly — basically every time it replicates. But not all mutations stick, and not all the ones that stick are bad. In fact, mutations are actually necessary for tracking and containing COVID-19. Here’s how viruses mutate and why you shouldn’t be worried when you hear about them.

MORE CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE:

What Could Be The Fastest Way To End The Coronavirus Crisis?

Will Warm Weather Stop COVID-19?

Why COVID-19 Death Predictions Will Always Be Wrong

——————————————————

#Coronavirus #Mutation #ScienceInsider

Science Insider tells you all you need to know about science: space, medicine, biotech, physiology, and more.

Visit us at: https://www.businessinsider.com

Science Insider on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BusinessInsiderScience/

Science Insider on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/science_insider/

Business Insider on Twitter: https://twitter.com/businessinsider

Tech Insider on Twitter: https://twitter.com/techinsider

Business Insider/Tech Insider on Amazon Prime: http://read.bi/PrimeVideo

——————————————————

How Viruses Like The Coronavirus Mutate

Mutation has become a

sort of genetic boogeyman. It’s a common trope in horror. In people, mutations cause disfigurement, aggression, even cannibalism. So it’s not surprising that the

conversation around mutation and the virus that causes

COVID-19 feels scary. But genetic mutations in real life aren’t like the ones we see in movies. And on a viral level, they could actually help us track and manage COVID-19. So, let’s break down what

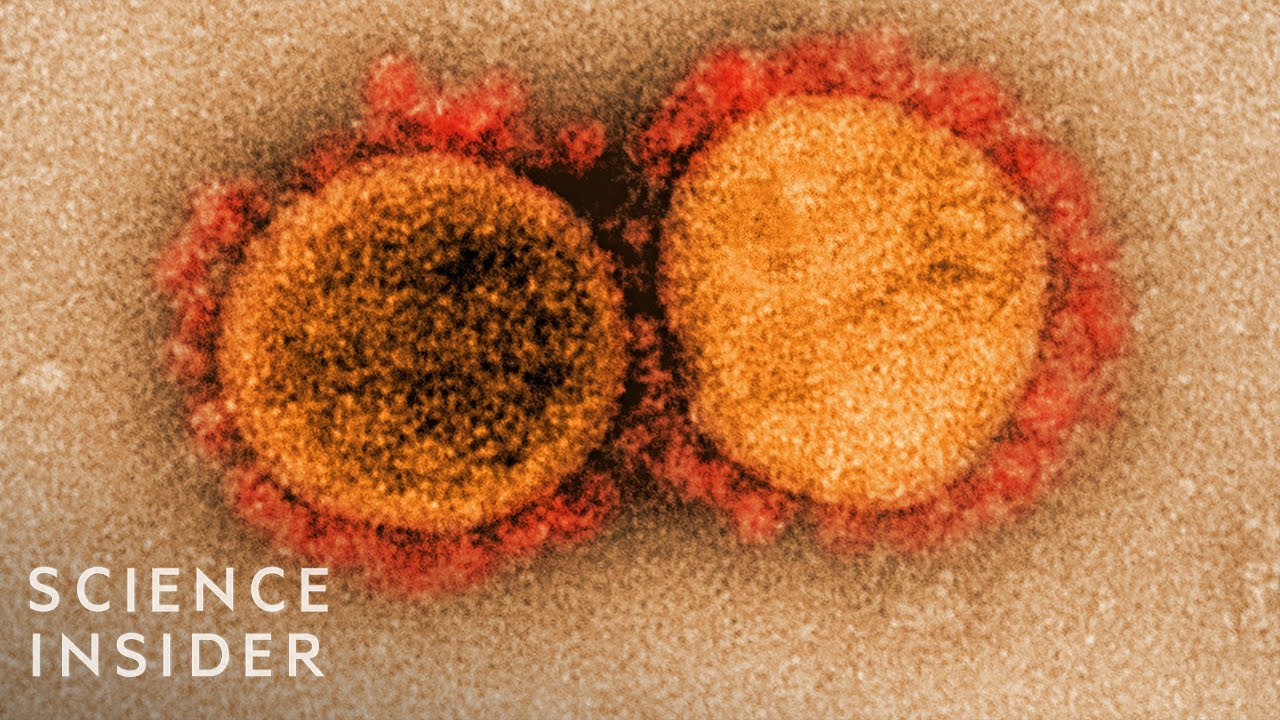

mutations actually are and what they could mean for the virus we’re facing right now. This is SARS-CoV-2, the

virus that causes COVID-19. It’s a type of RNA virus, some of which mutate practically

every time they replicate. SARS-CoV-2 is actually one

of the rare RNA viruses that has a proofreading mechanism that slows down its mutation rate some. Despite that, it has mutated, and it will continue to mutate. But that’s not as scary as it sounds. Mary Petrone: It’s basically a typo, or a mistake that occurs, like if you were writing an essay. Narrator: SARS-CoV-2’s RNA is basically a blueprint for making more SARS-CoV-2s, but viruses can’t replicate themselves. They have to hack into

another organism’s cells and use their machinery

to make new copies. Here’s how that process works. Petrone: The virus will,

like, let its genetic material free into the cytoplasm of the cell, and then when that genetic

material encounters what’s called a ribosome… Narrator: The ribosome

reads the virus’ blueprint and starts building a new virus. Petrone: Then it’ll read it

three nucleic acids at a time, so we’d call that a

codon, and they’re always three nucleic acids. And a combination of three nucleic acids corresponds to a single amino acid. Narrator: String those

amino acids together… Petrone: And that’s what

creates the protein. Narrator: But occasionally,

the wrong nucleic acid will get added to the chain. This can sometimes, but not always, lead to changes down the line, making that offspring virus slightly different from its parent. Each amino acid or

combination of amino acids is responsible for defining some characteristic of the virus. Things like its shape,

how infectious it is, what kind of organism it infects, and the types of cells it targets. So a mutation, or, more

likely, multiple mutations, has the potential to

change any of those things. Petrone: Theoretically,

everything is fair game because these, you know, mutations are totally random events. Narrator: But a mutation in a single virus only affects that one virus. For a mutation to stick, it has to be able to be passed on to new

generations and new hosts. So something that messes

with vital functions, like the virus’ ability to

replicate, means a dead end. In terms of the virus’ fitness, the probability of beneficial, neutral, and harmful mutations shifts based on the environment it’s in. Let’s say a virus is perfectly

suited to its environment. The virus doesn’t stop mutating, but it would be impossible for a mutation to make it even more perfect, so the likelihood of

mutations that are neutral or harmful for the virus are very high. It’s impossible to say SARS-CoV-2 is perfectly suited for infecting humans. But since it can move from person to person so efficiently, experts don’t think it’s facing

a lot of pressure to adapt. Plus, its two most

concerning characteristics, how contagious it is and

how harmful it can be, are controlled by multiple genes. So in order to become more

contagious or more harmful, the virus would need to undergo multiple beneficial mutations at

exactly the right time. That’s just not very likely. But Mary points out that

even talking about mutations in terms of “dangerous” or

“worse” can be subjective. Petrone: In my mind,

what makes this outbreak or this epidemic especially

concerning is that so many people who get

infected with the virus don’t really show symptoms, and that’s why it’s been

able to spread so far. But if there were to be

a change that, you know, made the virus, the infection,

much worse in people, in some ways, it’d be easier to control. So there are all of these

different trade-offs we need to think about. Narrator: Mutations

can actually be pivotal when it comes to fighting COVID-19. Since we know what

SARS-CoV-2’s genome looked like at the beginning of the outbreak, we can track when and where it changes. Petrone: We actually saw that

patients that we identified in Connecticut in the early

stages of the outbreak here, their virus was more closely related to viruses that were collected and sequenced in Washington state compared to in China or in Europe, for example. So, that actually tells us that we have domestic

transmission going on, and we are getting all this

information based off of mutations that have arisen in the virus. Narrator: There are a couple initiatives that are tracking this

data globally right now. One being Nextstrain, an open-source project

that tracks the spread and evolution of infectious

diseases in real time. Right now, it’s focused on COVID-19. Researchers can use that information to answer questions like: How fast is it mutating? Not very. Is it spreading by air travel? Definitely, especially early on. Will it mutate in a way that makes a potential vaccine

ineffective, like the flu? Petrone: People who design

the vaccines think about this. Like, this is something that’s

factored into vaccine design. So, typically, vaccines, they use these highly conserved targets. So, they’ll pick some

part of the virus that is not tolerant to a lot of change or to really any change. It can’t really mutate

away from the vaccine without, you know, compromising some other really crucial element of its life cycle. Narrator: Plus, the flu is unique in the way its genetic

material is structured. It’s an RNA virus too, but

its genome is segmented. The coronavirus genome is not. The segments translate to a

bunch of different proteins. So every time the body sees a new protein, it has to make an entirely different set of antibodies specifically

designed to fight it. We don’t know exactly

how often a new vaccine for COVID-19 will be necessary, but we do know the virus

doesn’t have the same flexibility when it comes to proteins. And experts have been looking

at another coronavirus, the one that causes

SARS, to get an idea of how we might handle this one. Immunity to that virus lasts

roughly two to three years. Since it and the new coronavirus share a significant amount

of genetic material, this could be a good estimate. If that’s the case, then a

vaccine should last just as long since the virus is mutating so slowly. And that’s really the point. The viral ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 did have to mutate in order to

jump from animals to people, but it most likely

happened very gradually, with a series of mutations over the course of many, many years. Petrone: The timescale is

really what matters here. At the end of the day, we

need to be thinking about how best we can control this outbreak in the US and also around the world, because if there’s no

ongoing transmission, there’s no mutations, and then we really won’t have to worry.