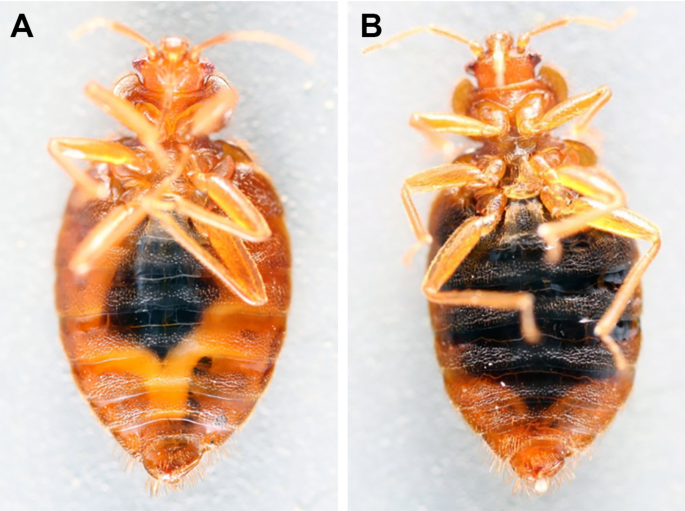

Insect colony maintenance

The C. lectularius used in this study was the Harold Harlan strain, also known as the Ft. Dix strain, originally collected at Fort Dix, New Jersey (USA) in 1973. This strain was maintained on a human host until December 2008, after which it was transitioned to an artificial feeder and defibrinated rabbit blood until July 2021, and finally to reconstituted human blood. In 2020, we generated a wCle-free lineage of the Harlan strain by treating bed bugs with rifampicin to eliminate wCle endosymbionts and then discontinued the use of the antibiotic5. This colony has remained wCle-free for many generations, as confirmed by digital droplet PCR43. By eliminating antibiotics as a confounding factor, we ensured that any observed effects in the wCle-free bed bugs could be attributed specifically to the absence of wCle rather than to antibiotic-related interference, including pharmacological side effects that can negatively impact physiological processes44,45.

In this study, bed bugs with their wCle endosymbionts are referred to as wCle-present (also +wCle), while aposymbiotic bed bugs are termed wCle-free (also –wCle). Unless otherwise stated, all bed bugs were maintained in 20 ml vials containing file folder paper as a substrate for sheltering and egg laying and capped with plankton netting that allowed air exchange and enabled feeding. Rearing conditions were consistent across experiments, with a temperature of 27 ± 0.5 °C, 35–45% relative humidity (RH), and a 12 h:12 h light: dark cycle. Colonies and experimental insects were fed reconstituted human blood (obtained from the American Red Cross under IRB #00000288 and protocol #2018-026) using an artificial feeding system, as previously described46. To prevent erythrocyte settling, we agitated the blood with a pipette every 5 min during feeding. In all experiments, the blood was supplemented with 1 mM ATP to stimulate feeding47, and the hematocrit of the blood was set to 40% using a microhematocrit centrifuge (XC-3012, C&A Scientific, Sterling, VA), well within the normal human range of 35–50%48. For colony maintenance, the wCle-free bed bugs received B-vitamin supplementation using the Kao and Michayluk (K&M) vitamin mix49 (Millipore Sigma, Cat#K3129), while the wCle-present bed bugs were not given any additional vitamins5,41. For dissections or insect homogenization, insects were anesthetized on ice for approximately 10 min.

B-vitamin solutions

Although the K&M vitamin mix was used for colony maintenance, for all recovery experiments involving the supplementation of B-vitamins to wCle-free bed bugs, we used vitamins in concentrations consistent with the Lake and Friend (L&F) vitamin mix50. Both the K&M and L&F vitamin mixes have been shown to recover nymphal development and reproduction when added to the blood meal of wCle-free bed bugs5,6. However, the L&F mix contains higher concentrations of B-vitamins, and in preliminary experiments, we observed that bed bugs fed this mix recovered blood digestion more effectively than on the K&M mix. Combinations of only five B-vitamins (all from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) – riboflavin (A14545), biotin (230095000), thiamine (148990100), pyridoxine (A12041), and folic acid (J62937) – were used for recovery experiments because these are the only B-vitamins which have complete or partial biosynthetic pathways within the genome of wCle11. Vitamin treatments used in recovery experiments are shown in Table 1. For colony maintenance and recovery experiments, 10 µl of a 100X vitamin stock solution was added to each 1 ml of blood just before feeding.

Table 1 Final concentrations of B-vitamins in the blood meal in recovery experiments with wCle-free bed bugs.Diuresis assays

After feeding colonies of wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs using the colony rearing practices described above, we selected replete (fully engorged) 5th instar bed bugs and placed them in separate 5.5 cm D × 4.8 cm H jars. Ten d later (3–5 d after adult emergence), we selected newly emerged males within a body mass range of 2.5–4.5 mg to minimize variability associated with blood meal size. There was no significant difference in the pre-feeding weights between wCle-present and wCle-free cohorts. These bed bugs were fed blood without B-vitamin supplementation and immediately weighed on an analytical balance. Bed bugs that fed to repletion were transferred individually into 7 ml glass vials containing file folder paper for sheltering. Vials were placed in an incubator at 27 ± 0.5 °C and 35–45% RH, and each bed bug was re-weighed hourly until 4 h post-feeding, and again at 24 h. To reduce the effect of variation in blood meal size in our analysis, we normalized the body mass measurements of each individual bed bug as proportions of the same individual’s body mass immediately after feeding (time 0) (Fig. 3). The non-normalized data are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S1. To evaluate the effects of B-vitamin supplementation, we repeated this experiment at 0 and 2 h post-feeding, with an additional treatment consisting of wCle-free bed bugs that received the full B-vitamin mix, as detailed in Table 1.

Erythrocyte lysis assays

We collected adult male wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs of mixed ages from their respective colony jars and starved them for 7–10 d prior to feeding on blood without B-vitamin supplementation. At designated time-points immediately after feeding (0 h), and at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 36 h post-feeding, we destructively sampled the anterior midgut (AMG) contents. We pierced the cuticle just below the elytra using a dissection pin and placed a calibrated 10 µl microcapillary pipette onto the resulting fluid droplet, allowing AMG contents to be drawn up by capillary action. The volume of AMG fluid collected was recorded, and each sample was brought to a final volume of 10 µl using cold 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1X protease inhibitor cocktail III (Millipore Sigma, Cat#539134) to limit premature erythrocyte lysis. We diluted each sample as necessary, and loaded 10 µl aliquots of each sample into a hemocytometer to obtain erythrocyte counts. Erythrocyte counts were used to calculate the original erythrocyte concentration in the AMG. Due to individual variation in the size of the blood meal and the rate of diuresis, we normalized erythrocyte concentrations to the average erythrocyte concentration at 4 h post-feeding (Fig. 4). This time-point corresponded to the peak erythrocyte concentration prior to significant cell lysis, as diuresis causes a transient increase in erythrocyte concentration (Supplementary Information Fig. S2).

Hemoglobin and albumin digestion assays

To evaluate hemoglobin and albumin digestion, we collected freshly fed adult male wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs of mixed ages from their respective colonies and starved them for 20 d before feeding on blood with no B-vitamin supplementation. At time-0 (immediately after feeding), whole wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs were homogenized in 100 µl of PBS using a disposable pestle; these samples were used to determine baseline amount of hemoglobin and albumin in the blood meal. We used whole insects at this time point due to the difficulty of dissecting midguts from fully engorged bed bugs without rupturing them. Preliminary results confirmed no significant difference in hemoglobin content between whole-insect homogenates and dissected midguts within the first 2 d post-feeding (Supplementary Information Fig. S5). At 2, 4, 6, and 8 d post-feeding, midguts were dissected following a protocol modified from51, homogenized as above, and stored at -20 °C until analysis. The initial sample size was 10 bed bugs per group per time point; however, midguts damaged during dissection were excluded from analysis, resulting in n = 6–10 (Fig. 5). We quantified hemoglobin content using a high-sensitivity colorimetric hemoglobin assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat#EIAHGBC), and albumin content using a BCG albumin assay (Millipore Sigma, Cat# MAK124), following the manufacturers’ protocols. The raw data was corrected for the dilution in PBS to obtain hemoglobin or albumin content per insect or per insect midgut. One data point was identified as an outlier, and subsequently removed from the analysis.

To assess the effect of B-vitamin supplementation, we collected 125 adult male wCle-free bed bugs as described above and randomly assigned them to five treatment groups (n = 25 per group): (1) no vitamins (control), (2) full vitamin mix (B2, B7, B1, B6, and B9), (3) B2 only, (4) B7 only, and (5) B1, B6 and B9 mix. Vitamin stock solutions were added (10 µl of 100X solution per 1 ml) to reconstituted blood, yielding the concentrations listed in Table 1. Immediately post-feeding (0 d), five whole bed bugs per treatment were individually homogenized to quantify initial hemoglobin and albumin content in the blood meal. At 4 and 8 d post-feeding, midguts from 10 individual bed bugs per treatment were dissected and analyzed using hemoglobin and albumin assays, as described previously.

Of note, during the vitamin rescue experiments (Figs. 6 and 7), there was a signifcant difference in the initial hemoglobin content in wCle-free bed bugs by vitamin treatment, with the B2 only and B1, B6, and B9 mix treatments resulting in signifcantly higher hemoglobin content in bed bug midguts when compared to the no vitamin treatment. A similar pattern was observed for albumin, but the affect was not statistically significant. Thus, individual data points at 4- and 8-days post feeding were normalized to the mean of that treatment at 0-days post feeding. The non-normalized data for hemoglobin and albumin are shown in Supplementary Information Figs. S3 and S4, respectively.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 17 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), except for the Friedman test, which was conducted in R version 4.2.3 (R Core Team). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of all data sets. Data from diuresis and erythrocyte lysis experiments were not normally distributed, so nonparametric tests were employed. It is important to note that erythrocyte lysis and protein digestion experiments involved destructive sampling, with different individuals measured at each time point. In contrast, the diuresis experiments used non-destructive methods, allowing repeated measurements of the same individuals over time. Diuresis data were assessed using the Friedman test, the non-parametric equivalent of a repeated measures ANOVA. Two wCle-present samples were excluded from the Friedman test (n = 13) because there was no data collected at 24 h post feeding, and this analysis required continuity for all samples across each time point. These two samples were retained for Wilcoxon tests and visualization (n = 13–15) shown in Fig. 3. A one-way ANCOVA was used to compare slopes of the hemoglobin and albumin digestion data, with the P-value reported as the interaction term of Wolbachia-status * days post feeding. The albumin data were linearized using a log-transformation prior to the ANCOVA. Unless otherwise stated, we used an α-level of 0.05 for all analyses. We present summary data as box plots, showing all the replicates. The box represents the interquartile interval (middle 50% of the replicates) and the black horizontal line within the box is the median. Whiskers indicate all data points to the furthest points within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and potential outliers shown as individual points. In cases where outlier analyses were conducted, we used the Robust Fit Outliers approach in JMP, using the quartile method and a K sigma value of 4.