Goldstein, G. et al. Isolation of a polypeptide that has lymphocyte-differentiating properties and is probably represented universally in living cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 72, 11–15 (1975).

Dikic, I. & Schulman, B. A. An expanded lexicon for the ubiquitin code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 273–287 (2023).

Otten, E. G. et al. Ubiquitylation of lipopolysaccharide by RNF213 during bacterial infection. Nature 594, 111–116 (2021). This study shows for the first time that a lipid molecule can be ubiquitinated and it identifies the E3 ligases that links detection of Gram-negative bacteria with its autophagic clearance.

Kelsall, I. R. et al. HOIL-1 ubiquitin ligase activity targets unbranched glucosaccharides and is required to prevent polyglucosan accumulation. EMBO J. 41, e109700 (2022).

Yang, C.-S. et al. Ubiquitin modification by the E3 ligase/ADP-ribosyltransferase Dtx3L/Parp9. Mol. Cell 66, 503–516.e5 (2017).

Tracz, M. & Bialek, W. Beyond K48 and K63: non-canonical protein ubiquitination. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 26, 1 (2021).

Clague, M. J., Urbé, S. & Komander, D. Breaking the chains: deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 338–352 (2019).

Ciechanover, A., Finley, D. & Varshavsky, A. Ubiquitin dependence of selective protein degradation demonstrated in the mammalian cell cycle mutant ts85. Cell 37, 57–66 (1984).

Bjørkøy, G. et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J. Cell Biol. 171, 603–614 (2005).

Lamark, T. & Johansen, T. Mechanisms of selective autophagy. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 37, 143–169 (2021).

Madiraju, C., Novack, J. P., Reed, J. C. & Matsuzawa, S. K63 ubiquitination in immune signaling. Trends Immunol. 43, 148–162 (2022).

Gao, L. et al. The mechanism of linear ubiquitination in regulating cell death and correlative diseases. Cell Death Dis. 14, 1–13 (2023).

Komander, D. et al. Molecular discrimination of structurally equivalent Lys 63-linked and linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO Rep. 10, 466–473 (2009).

Yang, Y., Fang, S., Jensen, J. P., Weissman, A. M. & Ashwell, J. D. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of IAPs and their degradation in proteasomes in response to apoptotic stimuli. Science 288, 874–877 (2000).

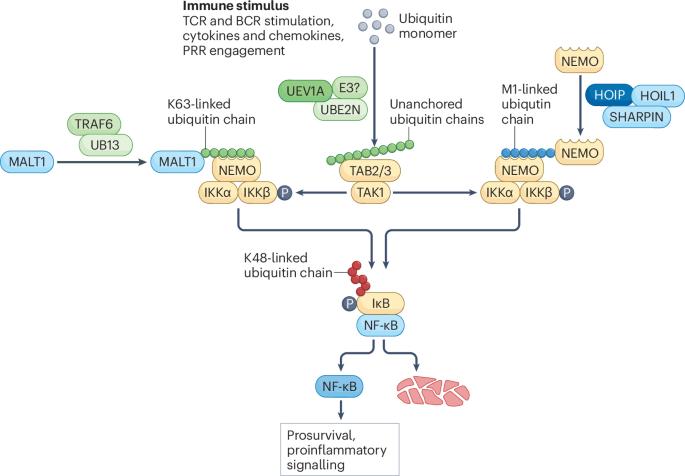

Deng, L. et al. Activation of the IκB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 103, 351–361 (2000).

Rahighi, S. et al. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by NEMO is important for NF-κB activation. Cell 136, 1098–1109 (2009).

Oeckinghaus, A. et al. Malt1 ubiquitination triggers NF-κB signaling upon T-cell activation. EMBO J. 26, 4634–4645 (2007).

Ni, X. et al. TRAF6 directs FOXP3 localization and facilitates regulatory T-cell function through K63-linked ubiquitination. EMBO J. 38, e99766 (2019).

Habelhah, H. et al. Ubiquitination and translocation of TRAF2 is required for activation of JNK but not of p38 or NF-κB. EMBO J. 23, 322–332 (2004).

Wang, X. et al. TRAF5-mediated Lys-63-linked polyubiquitination plays an essential role in positive regulation of RORγt in promoting IL-17A expression. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 29086–29094 (2015).

Hatakeyama, S. TRIM family proteins: roles in autophagy, immunity, and carcinogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 42, 297–311 (2017).

Versteeg, G. A. et al. The E3-ligase TRIM family of proteins regulates signaling pathways triggered by innate immune pattern-recognition receptors. Immunity 38, 384–398 (2013).

Gack, M. U. et al. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature 446, 916–920 (2007).

Sanchez, J. G. et al. TRIM25 binds RNA to modulate cellular anti-viral defense. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 5280–5293 (2018).

Tsuchida, T. et al. The ubiquitin ligase TRIM56 regulates innate immune responses to intracellular double-stranded DNA. Immunity 33, 765–776 (2010).

Liu, S. et al. MAVS recruits multiple ubiquitin E3 ligases to activate antiviral signaling cascades. eLife 2, e00785 (2013).

Ni, G., Konno, H. & Barber, G. N. Ubiquitination of STING at lysine 224 controls IRF3 activation. Sci. Immunol. 2, eaah7119 (2017).

Fukushima, T. et al. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13 is a critical component of TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-mediated inflammatory responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 6371–6376 (2007).

Jahan, A. S., Elbæk, C. R. & Damgaard, R. B. Met1-linked ubiquitin signalling in health and disease: inflammation, immunity, cancer, and beyond. Cell Death Differ. 28, 473–492 (2021).

Fiil, B. K. & Gyrd-Hansen, M. The Met1-linked ubiquitin machinery in inflammation and infection. Cell Death Differ. 28, 557–569 (2021).

Kirisako, T. et al. A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J. 25, 4877–4887 (2006). This study identifies the LUBAC subunits HOIL1 and HOIP and the is the first study to describe M1-linked ubiquitination.

Keusekotten, K. et al. OTULIN antagonizes LUBAC signaling by specifically hydrolyzing Met1-linked polyubiquitin. Cell 153, 1312–1326 (2013).

Rivkin, E. et al. The linear ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinase gumby regulates angiogenesis. Nature 498, 318–324 (2013).

Gerlach, B. et al. Linear ubiquitination prevents inflammation and regulates immune signalling. Nature 471, 591–596 (2011).

Ikeda, F. et al. SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature 471, 637–641 (2011).

Tokunaga, F. et al. SHARPIN is a component of the NF-κB-activating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Nature 471, 633–636 (2011). Together with Gerlach et al. (2011) and Ikeda et al. (2011), this study identifes the final subunit of the LUBAC complex, SHARPIN, and the connection between M1-linked ubiquitination and NF-κB signalling.

Emmerich, C. H. et al. Activation of the canonical IKK complex by K63/M1-linked hybrid ubiquitin chains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15247–15252 (2013). This study shows that LUBAC produces M1-linked ubiquitin chains in response to K63-linked ubiquitin chains, both of which activate NF-κB signalling.

Gyrd-Hansen, M. et al. IAPs contain an evolutionarily conserved ubiquitin-binding domain that regulates NF-κB as well as cell survival and oncogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1309–1317 (2008).

Boisson, B. et al. Immunodeficiency, autoinflammation and amylopectinosis in humans with inherited HOIL-1 and LUBAC deficiency. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1178–1186 (2012).

Heger, K. et al. OTULIN limits cell death and inflammation by deubiquitinating LUBAC. Nature 559, 120–124 (2018).

Haas, T. L. et al. Recruitment of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex stabilizes the TNF-R1 signaling complex and is required for TNF-mediated gene induction. Mol. Cell 36, 831–844 (2009).

Peltzer, N. et al. LUBAC is essential for embryogenesis by preventing cell death and enabling haematopoiesis. Nature 557, 112–117 (2018).

Xia, Z.-P. et al. Direct activation of protein kinases by unanchored polyubiquitin chains. Nature 461, 114–119 (2009).

Zeng, W. et al. Reconstitution of the RIG-I pathway reveals a signaling role of unanchored polyubiquitin chains in innate immunity. Cell 141, 315–330 (2010). Together with Xia et al. (2009), this study detects unanchored polyubiquitin chains synthesized by following IL-1β stimulation or infection and their role in immune activation.

Catici, D. A. M., Horne, J. E., Cooper, G. E. & Pudney, C. R. Polyubiquitin drives the molecular interactions of the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) by allosteric regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 14130–14139 (2015).

Skaug, B. et al. Direct, noncatalytic mechanism of IKK inhibition by A20. Mol. Cell 44, 559–571 (2011).

Rehwinkel, J. & Gack, M. U. RIG-I-like receptors: their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 537–551 (2020).

Song, B. et al. Ordered assembly of the cytosolic RNA-sensing MDA5-MAVS signaling complex via binding to unanchored K63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains. Immunity 54, 2218–2230.e5 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. MAVS-loaded unanchored Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains activate the RIG-I-MAVS signaling cascade. Cell Mol. Immunol. 20, 1186–1202 (2023).

Jiang, X. et al. Ubiquitin-induced oligomerization of the RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 activates antiviral innate immune response. Immunity 36, 959–973 (2012).

Rajsbaum, R. et al. Unanchored K48-linked polyubiquitin synthesized by the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM6 stimulates the interferon-IKKε kinase-mediated antiviral response. Immunity 40, 880–895 (2014).

Luo, H. Interplay between the virus and the ubiquitin–proteasome system: molecular mechanism of viral pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Virol. 17, 1–10 (2016).

Ko, A. et al. MKRN1 induces degradation of west nile virus capsid protein by functioning as an E3 ligase. J. Virol. 84, 426–436 (2010).

Shirakura, M. et al. E6AP ubiquitin ligase mediates ubiquitylation and degradation of hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Virol. 81, 1174–1185 (2007).

Apte, S. et al. An innate pathogen sensing strategy involving ubiquitination of bacterial surface proteins. Sci. Adv. 9, eade1851 (2023). This study identifies a bacterial degron, which is used by the human E3 ligase to recognize foreign protein.

Mallery, D. L. et al. Antibodies mediate intracellular immunity through tripartite motif-containing 21 (TRIM21). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19985–19990 (2010).

McEwan, W. A. et al. Intracellular antibody-bound pathogens stimulate immune signaling via the Fc receptor TRIM21. Nat. Immunol. 14, 327–336 (2013).

Rikihisa, Y. Glycogen autophagosomes in polymorphonuclear leukocytes induced by rickettsiae. Anat. Rec. 208, 319–327 (1984).

Mukherjee, R. & Dikic, I. Regulation of host–pathogen interactions via the ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 76, 211–233 (2022).

Noad, J. et al. LUBAC-synthesized linear ubiquitin chains restrict cytosol-invading bacteria by activating autophagy and NF-κB. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 1–10 (2017).

van Wijk, S. J. L. et al. Linear ubiquitination of cytosolic Salmonella Typhimurium activates NF-κB and restricts bacterial proliferation. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 1–10 (2017).

Huett, A. et al. The LRR and RING domain protein LRSAM1 Is an E3 ligase crucial for ubiquitin-dependent autophagy of intracellular Salmonella Typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe 12, 778–790 (2012).

Manzanillo, P. S. et al. The ubiquitin ligase parkin mediates resistance to intracellular pathogens. Nature 501, 512–516 (2013).

Zheng, Y. T. et al. The adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 targets invading bacteria to the autophagy pathway1. J. Immunol. 183, 5909–5916 (2009).

Wild, P. et al. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts salmonella growth. Science 333, 228–233 (2011).

Thurston, T. L. M., Ryzhakov, G., Bloor, S., von Muhlinen, N. & Randow, F. The TBK1 adaptor and autophagy receptor NDP52 restricts the proliferation of ubiquitin-coated bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1215–1221 (2009).

Dikic, I. & Elazar, Z. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 349–364 (2018).

Scheidel, J., Amstein, L., Ackermann, J., Dikic, I. & Koch, I. In silico knockout studies of xenophagic capturing of salmonella. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1005200 (2016).

Mostowy, S. et al. p62 and NDP52 proteins target intracytosolic shigella and listeria to different autophagy pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26987–26995 (2011).

Py, B. F., Lipinski, M. M. & Yuan, J. Autophagy limits listeria monocytogenes intracellular growth in the early phase of primary infection. Autophagy 3, 117–125 (2007).

Birmingham, C. L. et al. Listeria monocytogenes evades killing by autophagy during colonization of host cells. Autophagy 3, 442–451 (2007).

Gutierrez, M. G. et al. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119, 753–766 (2004).

Watson, R. O., Manzanillo, P. S. & Cox, J. S. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway. Cell 150, 803–815 (2012).

Pilli, M. et al. TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity 37, 223–234 (2012).

Casassa, A. F., Vanrell, M. C., Colombo, M. I., Gottlieb, R. A. & Romano, P. S. Autophagy plays a protective role against Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Virulence 10, 151–165 (2019).

Ling, Y. M. et al. Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2063–2071 (2006).

Paludan, C. et al. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science 307, 593–596 (2005).

Kim, N. et al. Interferon-inducible protein SCOTIN interferes with HCV replication through the autolysosomal degradation of NS5A. Nat. Commun. 7, 10631 (2016).

Sagnier, S. et al. Autophagy restricts HIV-1 infection by selectively degrading tat in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 89, 615–625 (2014).

Valera, M.-S. et al. The HDAC6/APOBEC3G complex regulates HIV-1 infectiveness by inducing Vif autophagic degradation. Retrovirology 12, 53 (2015).

Choi, Y., Bowman, J. W. & Jung, J. U. Autophagy during viral infection — a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 341–354 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Control of infection by LC3-associated phagocytosis, CASM, and detection of raised vacuolar pH by the V-ATPase-ATG16L1 axis. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn3298 (2022).

Sanjuan, M. A. et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature 450, 1253–1257 (2007).

Prado, M. et al. Long-term live imaging reveals cytosolic immune responses of host hepatocytes against plasmodium infection and parasite escape mechanisms. Autophagy 11, 1561–1579 (2015).

Murata, S., Takahama, Y., Kasahara, M. & Tanaka, K. The immunoproteasome and thymoproteasome: functions, evolution and human disease. Nat. Immunol. 19, 923–931 (2018).

Kroemer, G., Galassi, C., Zitvogel, L. & Galluzzi, L. Immunogenic cell stress and death. Nat. Immunol. 23, 487–500 (2022).

Lopez-Castejon, G. Control of the inflammasome by the ubiquitin system. FEBS J. 287, 11–26 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. USP18 antagonizes pyroptosis by facilitating selective autophagic degradation of gasdermin D. Research 7, 0380 (2024).

Humphries, F. et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase pellino2 mediates priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat. Commun. 9, 1560 (2018).

Guan, K. et al. MAVS promotes inflammasome activation by targeting ASC for K63-linked ubiquitination via the E3 ligase TRAF3. J. Immunol. 194, 4880–4890 (2015).

Duong, B. H. et al. A20 restricts ubiquitination of pro-interleukin-1β protein complexes and suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activity. Immunity 42, 55–67 (2015).

Shi, Y. et al. E3 ubiquitin ligase SYVN1 is a key positive regulator for GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 13, 1–14 (2022).

Roberts, J. Z., Crawford, N. & Longley, D. B. The role of ubiquitination in apoptosis and necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 29, 272–284 (2022).

de Almagro, M. C. et al. Coordinated ubiquitination and phosphorylation of RIP1 regulates necroptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 24, 26–37 (2017).

Onizawa, M. et al. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 restricts ubiquitination of the kinase RIPK3 and protects cells from necroptosis. Nat. Immunol. 16, 618–627 (2015).

Douglas, T. & Saleh, M. Post-translational modification of OTULIN regulates ubiquitin dynamics and cell death. Cell Rep. 29, 3652–3663.e5 (2019).

Tang, Y. et al. K63-linked ubiquitination regulates RIPK1 kinase activity to prevent cell death during embryogenesis and inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10, 4157 (2019).

Li, H., Kobayashi, M., Blonska, M., You, Y. & Lin, X. Ubiquitination of RIP is required for tumor necrosis factor α-induced NF-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13636–13643 (2006).

Liccardi, G. & Annibaldi, A. MLKL post-translational modifications: road signs to infection, inflammation and unknown destinations. Cell Death Differ. 30, 269–278 (2023).

Garcia, L. R. et al. Ubiquitylation of MLKL at lysine 219 positively regulates necroptosis-induced tissue injury and pathogen clearance. Nat. Commun. 12, 3364 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Oligomerization-driven MLKL ubiquitylation antagonizes necroptosis. EMBO J. 40, e103718 (2021).

Yoon, S., Bogdanov, K. & Wallach, D. Site-specific ubiquitination of MLKL targets it to endosomes and targets listeria and yersinia to the lysosomes. Cell Death Differ. 29, 306–322 (2022). Together with Garcia et al. (2021) and Liu et al. (2021), this study describes the complex regulation of MLKL by ubiquitination, suggesting several checkpoints before necroptotic cell death.

Dupont, N. et al. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J. 30, 4701–4711 (2011).

Nakahira, K. et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 12, 222–230 (2011).

Harris, J. et al. Autophagy controls IL-1β secretion by targeting pro-IL-1β for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9587–9597 (2011).

Piletic, K., Alsaleh, G. & Simon, A. K. Autophagy orchestrates the crosstalk between cells and organs. EMBO Rep. 24, e57289 (2023).

Wang, L.-J. et al. The microtubule-associated protein EB1 links AIM2 inflammasomes with autophagy-dependent secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 29322–29333 (2014).

Zhang, M., Kenny, S. J., Ge, L., Xu, K. & Schekman, R. Translocation of interleukin-1β into a vesicle intermediate in autophagy-mediated secretion. eLife 4, e11205 (2015).

Zhang, M. et al. A translocation pathway for vesicle-mediated unconventional protein secretion. Cell 181, 637–652.e15 (2020).

Kimura, T. et al. Dedicated SNAREs and specialized TRIM cargo receptors mediate secretory autophagy. EMBO J. 36, 42–60 (2017).

Roberts, C. G., Franklin, T. G. & Pruneda, J. N. Ubiquitin-targeted bacterial effectors: rule breakers of the ubiquitin system. EMBO J. 42, e114318 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. Glutamine deamidation and dysfunction of ubiquitin/NEDD8 induced by a bacterial effector family. Science 329, 1215–1218 (2010).

Jubelin, G. et al. Pathogenic bacteria target NEDD8-conjugated Cullins to hijack host–cell signaling pathways. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001128 (2010).

Morikawa, H. et al. The bacterial effector Cif interferes with SCF ubiquitin ligase function by inhibiting deneddylation of Cullin1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 401, 268–274 (2010).

Gan, N., Nakayasu, E. S., Hollenbeck, P. J. & Luo, Z.-Q. Legionella pneumophila inhibits immune signalling via MavC-mediated transglutaminase-induced ubiquitination of UBE2N. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 134–143 (2019).

Valleau, D. et al. Discovery of ubiquitin deamidases in the pathogenic arsenal of Legionella pneumophila. Cell Rep. 23, 568–583 (2018).

Sanada, T. et al. The shigella flexneri effector OspI deamidates UBC13 to dampen the inflammatory response. Nature 483, 623–626 (2012).

Toro, T. B., Toth, J. I. & Petroski, M. D. The cyclomodulin cycle inhibiting factor (CIF) alters Cullin neddylation dynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14716–14726 (2013).

Ashida, H., Kim, M. & Sasakawa, C. Exploitation of the host ubiquitin system by human bacterial pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 399–413 (2014).

Bailey-Elkin, B. A., Knaap, R. C. M., Kikkert, M. & Mark, B. L. Structure and function of viral deubiquitinating enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 3441–3470 (2017).

Sánchez-Alba, L., Borràs-Gas, H., Huang, G., Varejão, N. & Reverter, D. Structural diversity of the CE-clan proteases in bacteria to disarm host ubiquitin defenses. Trends Biochem. Sci. 49, 1111–1123 (2024).

Balakirev, M. Y., Jaquinod, M., Haas, A. L. & Chroboczek, J. Deubiquitinating function of adenovirus proteinase. J. Virol. 76, 6323–6331 (2002).

Inn, K.-S. et al. Inhibition of RIG-I-mediated signaling by kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded deubiquitinase ORF64. J. Virol. 85, 10899–10904 (2011).

Sun, L. et al. Coronavirus papain-like proteases negatively regulate antiviral innate immune response through disruption of STING-mediated signaling. PLoS ONE 7, e30802 (2012).

Xing, Y. et al. The papain-like protease of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus negatively regulates type I interferon pathway by acting as a viral deubiquitinase. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 1554–1567 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. SARS coronavirus papain-like protease inhibits the type I interferon signaling pathway through interaction with the STING–TRAF3–TBK1 complex. Protein Cell 5, 369–381 (2014).

Wang, D. et al. The leader proteinase of foot-and-mouth disease virus negatively regulates the type I interferon pathway by acting as a viral deubiquitinase. J. Virol. 85, 3758–3766 (2011).

van Kasteren, P. B. et al. Arterivirus and nairovirus ovarian tumor domain-containing deubiquitinases target activated RIG-I to control innate immune signaling. J. Virol. 86, 773–785 (2012).

Gastaldello, S. et al. A deneddylase encoded by epstein–barr virus promotes viral DNA replication by regulating the activity of Cullin-RING ligases. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 351–361 (2010).

Békés, M. et al. SARS hCoV papain-like protease is a unique Lys48 linkage-specific di-distributive deubiquitinating enzyme. Biochem. J. 468, 215–226 (2015).

Misaghi, S. et al. Chlamydia trachomatis-derived deubiquitinating enzymes in mammalian cells during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 142–150 (2006).

Pruneda, J. N. et al. The molecular basis for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like specificities in bacterial effector proteases. Mol. Cell 63, 261–276 (2016).

Hermanns, T. & Hofmann, K. Bacterial DUBs: deubiquitination beyond the seven classes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 47, 1857–1866 (2019).

Tan, K. S. et al. Suppression of host innate immune response by burkholderia pseudomallei through the virulence factor TssM. J. Immunol. 184, 5160–5171 (2010).

Le Negrate, G. et al. Salmonella secreted factor L deubiquitinase of Salmonella typhimurium inhibits NF-κB, suppresses IκBα ubiquitination and modulates innate immune responses. J. Immunol. 180, 5045–5056 (2008).

Huang, J. & Brumell, J. H. Bacteria–autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 101–114 (2014).

Aguilera, M. O., Delgui, L. R., Reggiori, F., Romano, P. S. & Colombo, M. I. Autophagy as an innate immunity response against pathogens: a Tango dance. FEBS Lett. 598, 140–166 (2024).

Tattoli, I. et al. Amino acid starvation induced by invasive bacterial pathogens triggers an innate host defense program. Cell Host Microbe 11, 563–575 (2012). This study describes the complex interplay between metabolism, autophagy and cell-autonomous immune response to different intracellular bacteria.

Ganesan, R. et al. Salmonella Typhimurium disrupts Sirt1/AMPK checkpoint control of mTOR to impair autophagy. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006227 (2017).

Orvedahl, A. et al. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe 1, 23–35 (2007).

Chaumorcel, M. et al. The human cytomegalovirus protein TRS1 inhibits autophagy via its interaction with beclin 1. J. Virol. 86, 2571–2584 (2012).

Mouna, L. et al. Analysis of the role of autophagy inhibition by two complementary human cytomegalovirus BECN1/Beclin 1-binding proteins. Autophagy 12, 327–342 (2016).

Dong, N. et al. Structurally distinct bacterial TBC-like GAPs link Arf GTPase to Rab1 inactivation to counteract host defenses. Cell 150, 1029–1041 (2012).

Feng, Z.-Z. et al. The Salmonella effectors SseF and SseG inhibit Rab1A-mediated autophagy to facilitate intracellular bacterial survival and replication. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 9662–9673 (2018).

Barnett, T. C. et al. The globally disseminated M1T1 clone of group A Streptococcus evades autophagy for intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe 14, 675–682 (2013).

Choy, A. et al. The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science 338, 1072–1076 (2012).

Real, E. et al. Plasmodium UIS3 sequesters host LC3 to avoid elimination by autophagy in hepatocytes. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 17–25 (2018).

Lennemann, N. J. & Coyne, C. B. Dengue and Zika viruses subvert reticulophagy by NS2B3-mediated cleavage of FAM134B. Autophagy 13, 322–332 (2017).

Yoshikawa, Y. et al. Listeria monocytogenes ActA-mediated escape from autophagic recognition. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1233–1240 (2009).

Niklaus, L. et al. Deciphering host lysosome-mediated elimination of plasmodium berghei liver stage parasites. Sci. Rep. 9, 7967 (2019).

Agop-Nersesian, C. et al. Shedding of host autophagic proteins from the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane of plasmodium berghei. Sci. Rep. 7, 2191 (2017).

Abramovitch, R. B., Janjusevic, R., Stebbins, C. E. & Martin, G. B. Type III effector AvrPtoB requires intrinsic E3 ubiquitin ligase activity to suppress plant cell death and immunity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2851–2856 (2006).

Janjusevic, R., Abramovitch, R. B., Martin, G. B. & Stebbins, C. E. A bacterial inhibitor of host programmed cell death defenses is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science 311, 222–226 (2006). This study is the first E3 ligase of bacterial origin to be described.

Rosebrock, T. R. et al. A bacterial E3 ubiquitin ligase targets a host protein kinase to disrupt plant immunity. Nature 448, 370–374 (2007).

Gimenez-Ibanez, S. et al. AvrPtoB targets the LysM receptor kinase CERK1 to promote bacterial virulence on plants. Curr. Biol. 19, 423–429 (2009).

Abramovitch, R. B., Kim, Y., Chen, S., Dickman, M. B. & Martin, G. B. Pseudomonas type III effector AvrPtoB induces plant disease susceptibility by inhibition of host programmed cell death. EMBO J. 22, 60–69 (2003).

Wu, B. et al. NleG type 3 effectors from enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli are U-box E3 ubiquitin ligases. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000960 (2010).

Kubori, T., Hyakutake, A. & Nagai, H. Legionella translocates an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has multiple U-boxes with distinct functions. Mol. Microbiol. 67, 1307–1319 (2008).

Lin, Y.-H. et al. Host Cell-catalyzed S-palmitoylation mediates golgi targeting of the Legionella ubiquitin ligase GobX. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 25766–25781 (2015).

Lin, Y.-H. et al. RavN is a member of a previously unrecognized group of Legionella pneumophila E3 ubiquitin ligases. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006897 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Higashide, W. M., McCormick, B. A., Chen, J. & Zhou, D. The inflammation-associated Salmonella SopA is a HECT-like E3 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 786–793 (2006).

Lin, D. Y., Diao, J., Zhou, D. & Chen, J. Biochemical and structural studies of a HECT-like ubiquitin ligase from Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 441–449 (2011).

Singer, A. U. et al. A pathogen type III effector with a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase architecture. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003121 (2013).

Rohde, J. R., Breitkreutz, A., Chenal, A., Sansonetti, P. J. & Parsot, C. Type III secretion effectors of the IpaH family are E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell Host Microbe 1, 77–83 (2007).

Singer, A. U. et al. Structure of the shigella T3SS effector IpaH defines a new class of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1293–1301 (2008).

Zhu, Y. et al. Structure of a shigella effector reveals a new class of ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1302–1308 (2008). This study, together with Rohde et al. (2007) and Singer et al. (2008), describes the identification and structural characterization of new bacterial E3 ligases.

Sandstrom, A. et al. Functional degradation: a mechanism of NLRP1 inflammasome activation by diverse pathogen enzymes. Science 364, eaau1330 (2019).

Ashida, H. et al. A bacterial E3 ubiquitin ligase IpaH9.8 targets NEMO/IKKγ to dampen the host NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 66–73 (2010).

de Jong, M. F., Liu, Z., Chen, D. & Alto, N. M. Shigella flexneri suppresses NF-κB activation by inhibiting linear ubiquitin chain ligation. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 1–11 (2016).

Suzuki, S. et al. Shigella IpaH7.8 E3 ubiquitin ligase targets glomulin and activates inflammasomes to demolish macrophages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E4254–E4263 (2014).

Hansen, J. M. et al. Pathogenic ubiquitination of GSDMB inhibits NK cell bactericidal functions. Cell 184, 3178–3191.e18 (2021).

Luchetti, G. et al. Shigella ubiquitin ligase IpaH7.8 targets gasdermin D for degradation to prevent pyroptosis and enable infection. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1521–1530.e10 (2021).

Haraga, A. & Miller, S. I. A Salmonella type III secretion effector interacts with the mammalian serine/threonine protein kinase PKN1. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 837–846 (2006).

Bernal-Bayard, J. & Ramos-Morales, F. Salmonella type III secretion effector SlrP is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for mammalian thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27587–27595 (2009).

Quezada, C. M., Hicks, S. W., Galán, J. E. & Stebbins, C. E. A family of Salmonella virulence factors functions as a distinct class of autoregulated E3 ubiquitin ligases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4864–4869 (2009).

Herod, A. et al. Genomic and phenotypic analysis of SspH1 identifies a new Salmonella effector, SspH3. Mol. Microbiol. 117, 770–789 (2022).

Chou, Y.-C., Keszei, A. F. A., Rohde, J. R., Tyers, M. & Sicheri, F. Conserved structural mechanisms for autoinhibition in IpaH ubiquitin ligases. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 268–275 (2012).

Keszei, A. F. A. et al. Structure of an SspH1–PKN1 complex reveals the basis for host substrate recognition and mechanism of activation for a bacterial E3 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 362–373 (2014).

Xu, C.-C., Zhang, D., Hann, D. R., Xie, Z.-P. & Staehelin, C. Biochemical properties and in planta effects of NopM, a rhizobial E3 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 15304–15315 (2018).

Nakano, M., Oda, K. & Mukaihara, T. Ralstonia solanacearum novel E3 ubiquitin ligase (NEL) effectors RipAW and RipAR suppress pattern-triggered immunity in plants. Microbiology 163, 992–1002 (2017).

Cheng, D. et al. Ralstonia solanacearum type III effector RipV2 encoding a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase (NEL) is required for full virulence by suppressing plant PAMP-triggered immunity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 550, 120–126 (2021).

Hsu, F. et al. The Legionella effector SidC defines a unique family of ubiquitin ligases important for bacterial phagosomal remodeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10538–10543 (2014).

Horenkamp, F. A. et al. Legionella pneumophila subversion of host vesicular transport by SidC effector proteins. Traffic 15, 488–499 (2014).

Kubori, T., Arasaki, K., Kitao, T. & Nagai, H. Multi-tiered actions of Legionella effectors to modulate host Rab10 dynamics. eLife 12, RP89002 (2023).

Boname, J. M. & Stevenson, P. G. MHC class I ubiquitination by a Viral PHD/LAP finger protein. Immunity 15, 627–636 (2001).

Cadwell, K. & Coscoy, L. Ubiquitination on nonlysine residues by a Viral E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science 309, 127–130 (2005).

Hagglund, R., Van Sant, C., Lopez, P. & Roizman, B. Herpes simplex virus 1-infected cell protein 0 contains two E3 ubiquitin ligase sites specific for different E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 631–636 (2002).

Lilley, C. E. et al. A viral E3 ligase targets RNF8 and RNF168 to control histone ubiquitination and DNA damage responses. EMBO J. 29, 943–955 (2010).

Shahnazaryan, D. et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 targets IRF7 via ICP0 to limit type I IFN induction. Sci. Rep. 10, 22216 (2020).

Parameswaran, P., Payne, L., Powers, J., Rashighi, M. & Orzalli, M. H. A viral E3 ubiquitin ligase produced by herpes simplex virus 1 inhibits the NLRP1 inflammasome. J. Exp. Med. 221, e20231518 (2024).

Cai, Q.-L., Knight, J. S., Verma, S. C., Zald, P. & Robertson, E. S. EC5S ubiquitin complex is recruited by KSHV latent antigen LANA for degradation of the VHL and p53 tumor suppressors. PLoS Pathog. 2, e116 (2006).

Odon, V., Georgana, I., Holley, J., Morata, J. & Maluquer de Motes, C. Novel class of viral ankyrin proteins targeting the host E3 ubiquitin ligase Cullin-2. J. Virol. 92, e01374-18 (2018).

Bratke, K. A., McLysaght, A. & Rothenburg, S. A survey of host range genes in poxvirus genomes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 14, 406–425 (2013).

Qiu, J. et al. Ubiquitination independent of E1 and E2 enzymes by bacterial effectors. Nature 533, 120–124 (2016). This study describes the identification of the SidE family of proteins in Legionella, which ubiquitinates substrates using only one enzyme.

Bhogaraju, S. et al. Phosphoribosylation of ubiquitin promotes serine ubiquitination and impairs conventional ubiquitination. Cell 167, 1636–1649.e13 (2016). This paper describes the mechanism of phosphoribosyl-ubiquitination, with the key first step: the ADP-ribosylation of ubiquitin.

Kalayil, S. et al. Insights into catalysis and function of phosphoribosyl-linked serine ubiquitination. Nature 557, 734–738 (2018).

Dong, Y. et al. Structural basis of ubiquitin modification by the Legionella effector SdeA. Nature 557, 674–678 (2018).

Akturk, A. et al. Mechanism of phosphoribosyl-ubiquitination mediated by a single Legionella effector. Nature 557, 729–733 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. Members of the Legionella pneumophila Sde family target tyrosine residues for phosphoribosyl-linked ubiquitination. RSC Chem. Biol. 2, 1509–1519 (2021).

Kim, R. Q. et al. Development of ADPribosyl ubiquitin analogues to study enzymes involved in Legionella infection. Chem. A 27, 2506–2512 (2021).

Shin, D. et al. Regulation of phosphoribosyl-linked serine ubiquitination by deubiquitinases DupA and DupB. Mol. Cell 77, 164–179.e6 (2020).

Wan, M. et al. Deubiquitination of phosphoribosyl-ubiquitin conjugates by phosphodiesterase-domain–containing Legionella effectors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 23518–23526 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. Legionella effector LnaB is a phosphoryl-AMPylase that impairs phosphosignalling. Nature 631, 393–401 (2024).

Fu, J. et al. Legionella maintains host cell ubiquitin homeostasis by effectors with unique catalytic mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 15, 5953 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Legionella metaeffector MavL reverses ubiquitin ADP-ribosylation via a conserved arginine-specific macrodomain. Nat. Commun. 15, 2452 (2024).

Kotewicz, K. M. et al. A single Legionella effector catalyzes a multistep ubiquitination pathway to rearrange tubular endoplasmic reticulum for replication. Cell Host Microbe 21, 169–181 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Serine-ubiquitination regulates Golgi morphology and the secretory pathway upon Legionella infection. Cell Death Differ. 28, 2957–2969 (2021).

Mukherjee, R. et al. Serine ubiquitination of SQSTM1 regulates NFE2L2-dependent redox homeostasis. Autophagy 21, 407–423 (2024).

Ge, J. et al. Phosphoribosyl-linked serine ubiquitination of USP14 by the SidE family effectors of Legionella excludes p62 from the bacterial phagosome. Cell Rep. 42, 112817 (2023).

Kotewicz, K. M. et al. Sde proteins coordinate ubiquitin utilization and phosphoribosylation to establish and maintain the Legionella replication vacuole. Nat. Commun. 15, 7479 (2024).

Wan, M. et al. Phosphoribosyl modification of poly-ubiquitin chains at the Legionella-containing vacuole prohibiting autophagy adaptor recognition. Nat. Commun. 15, 7481 (2024).

Mukherjee, R. et al. Phosphoribosyl ubiquitination of SNARE proteins regulates autophagy during Legionella infection. EMBO J. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44318-025-00483-4 (2025).

Bhogaraju, S. et al. Inhibition of bacterial ubiquitin ligases by SidJ-calmodulin catalysed glutamylation. Nature 572, 382–386 (2019).

Gan, N. et al. Regulation of phosphoribosyl ubiquitination by a calmodulin-dependent glutamylase. Nature 572, 387–391 (2019).

Black, M. H. et al. Bacterial pseudokinase catalyzes protein polyglutamylation to inhibit the SidE-family ubiquitin ligases. Science 364, 787–792 (2019).

Sulpizio, A. et al. Protein polyglutamylation catalyzed by the bacterial calmodulin-dependent pseudokinase SidJ. eLife 8, e51162 (2019).

Adams, M. et al. Structural basis for protein glutamylation by the Legionella pseudokinase SidJ. Nat. Commun. 12, 6174 (2021).

Song, L. et al. The Legionella effector SdjA is a bifunctional enzyme that distinctly regulates phosphoribosyl ubiquitination. mBio 12, e0231621 (2021).

Jeong, K. C., Sexton, J. A. & Vogel, J. P. Spatiotemporal regulation of a Legionella pneumophila T4SS substrate by the metaeffector SidJ. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004695 (2015).

Jackson, W. T. et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 3, e156 (2005).

Prentice, E., Jerome, W. G., Yoshimori, T., Mizushima, N. & Denison, M. R. Coronavirus replication complex formation utilizes components of cellular autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10136–10141 (2004).

Wang, L., Tian, Y. & Ou, J. J. HCV induces the expression of rubicon and UVRAG to temporally regulate the maturation of autophagosomes and viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004764 (2015).

Moreau, K. et al. Autophagosomes can support Yersinia pseudotuberculosis replication in macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 1108–1123 (2010).

Schnaith, A. et al. Staphylococcus aureus subvert autophagy for induction of caspase-independent host cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2695–2706 (2007).

Gutierrez, M. G. et al. Autophagy induction favours the generation and maturation of the coxiella-replicative vacuoles. Cell. Microbiol. 7, 981–993 (2005).

Romano, P. S., Gutierrez, M. G., Berón, W., Rabinovitch, M. & Colombo, M. I. The autophagic pathway is actively modulated by phase II Coxiella burnetii to efficiently replicate in the host cell. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 891–909 (2007).

Vázquez, C. L. & Colombo, M. I. Coxiella burnetii modulates Beclin 1 and Bcl-2, preventing host cell apoptosis to generate a persistent bacterial infection. Cell Death Differ. 17, 421–438 (2010).

Winchell, C. G. et al. Coxiella burnetii subverts p62/sequestosome 1 and activates Nrf2 signaling in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 86, e00608-17 (2018).

Kreibich, S. et al. Autophagy proteins promote repair of endosomal membranes damaged by the salmonella type three secretion system 1. Cell Host Microbe 18, 527–537 (2015). This study describes host cell autophagy used by Salmonella for repairing damage in its vacuole.

Thieleke-Matos, C. et al. Host cell autophagy contributes to plasmodium liver development. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 437–450 (2016).

Harrigan, J. A., Jacq, X., Martin, N. M. & Jackson, S. P. Deubiquitylating enzymes and drug discovery: emerging opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 17, 57–78 (2018).

Nanduri, B., Suvarnapunya, A. E., Venkatesan, M. & Edelmann, M. J. Deubiquitinating enzymes as promising drug targets for infectious diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 3234–3247 (2013).

Kennedy, C. R. et al. Covalent fragment screening to inhibit the E3 ligase activity of bacterial NEL enzymes SspH1 and SspH2. RSC Chem. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1039/d5cb00177c (2025).

Kimmey, J. M. & Stallings, C. L. Bacterial pathogens versus autophagy: implications for therapeutic interventions. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 1060–1076 (2016).

Andersson, A.-M. et al. Autophagy induction targeting mTORC1 enhances Mycobacterium tuberculosis replication in HIV co-infected human macrophages. Sci. Rep. 6, 28171 (2016).

Lee, Y. J. et al. Chemical modulation of SQSTM1/p62-mediated xenophagy that targets a broad range of pathogenic bacteria. Autophagy 18, 2926–2945 (2022).

Setua, S. et al. Disrupting plasmodium UIS3–host LC3 interaction with a small molecule causes parasite elimination from host cells. Commun. Biol. 3, 1–10 (2020).

Espinoza-Chávez, R. M. et al. Targeted protein degradation for infectious diseases: from basic biology to drug discovery. ACS Bio Med. Chem. Au 3, 32–45 (2023).

Takahashi, D. et al. AUTACs: cargo-specific degraders using selective autophagy. Mol. Cell 76, 797–810.e10 (2019).

de Wispelaere, M. et al. Small molecule degraders of the hepatitis C virus protease reduce susceptibility to resistance mutations. Nat. Commun. 10, 3468 (2019).

Xu, Z. et al. Discovery of oseltamivir-based novel PROTACs as degraders targeting neuraminidase to combat H1N1 influenza virus. Cell Insight 1, 100030 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Discovery of pentacyclic triterpenoid PROTACs as a class of effective hemagglutinin protein degraders. J. Med. Chem. 65, 7154–7169 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. An anti-influenza A virus microbial metabolite acts by degrading viral endonuclease PA. Nat. Commun. 13, 2079 (2022).

Desantis, J. et al. Indomethacin-based PROTACs as pan-coronavirus antiviral agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 226, 113814 (2021).

Hahn, F. et al. Development of a PROTAC-based targeting strategy provides a mechanistically unique mode of anti-cytomegalovirus activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12858 (2021).

Li, H. et al. PROTAC targeting cyclophilin A controls virus-induced cytokine storm. iScience 26, 107535 (2023).

Morreale, F. E. et al. BacPROTACs mediate targeted protein degradation in bacteria. Cell 185, 2338–2353.e18 (2022).

Ishii, M. & Akiyoshi, B. Targeted protein degradation using deGradFP in Trypanosoma brucei. Wellcome Open. Res. 7, 175 (2022).

Mangano, K. et al. VIPER-TACs leverage viral E3 ligases for disease-specific targeted protein degradation. Cell Chem. Biol. 32, 423–433.e9 (2025).

Si, L. et al. Generation of a live attenuated influenza A vaccine by proteolysis targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1370–1377 (2022). This study describes leveraging the proteasome to produce attenuated viruses that can be used for vaccination.

Zhong, G., Chang, X., Xie, W. & Zhou, X. Targeted protein degradation: advances in drug discovery and clinical practice. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 308 (2024).

Mello-Vieira, J., Bopp, T. & Dikic, I. Ubiquitination and cell-autonomous immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 84, 102368 (2023).

Goncharov, T. et al. Simultaneous substrate and ubiquitin modification recognition by bispecific antibodies enables detection of ubiquitinated RIP1 and RIP2. Sci. Signal. 17, eabn1101 (2024).

Słabicki, M. et al. The CDK inhibitor CR8 acts as a molecular glue degrader that depletes cyclin K. Nature 585, 293–297 (2020).

Huang, H.-T. et al. Ubiquitin-specific proximity labeling for the identification of E3 ligase substrates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1227–1236 (2024).

Mukhopadhyay, U. et al. A ubiquitin-specific, proximity-based labeling approach for the identification of ubiquitin ligase substrates. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp3000 (2024). Together with Huang et al. (2024), this study describes a proximity-labelling method to detect substrates of E3 ligases.

Xu, G. et al. Multiomics approach reveals the ubiquitination-specific processes hijacked by SARS-CoV-2. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 312 (2022).

Amstein, L. K. et al. Mathematical modeling of the molecular switch of TNFR1-mediated signaling pathways applying Petri net formalism and in silico knockout analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010383 (2022).

Hochstrasser, M. Origin and function of ubiquitin-like proteins. Nature 458, 422–429 (2009).

Shin, D. et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature 587, 657–662 (2020).

Dzimianski, J. V., Scholte, F. E. M., Bergeron, É & Pegan, S. D. ISG15: it’s complicated. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 4203–4216 (2019).

Ma, X., Zhao, C., Xu, Y. & Zhang, H. Roles of host SUMOylation in bacterial pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 91, e00283–23 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. SUMOylation in viral replication and antiviral defense. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104126 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. UFMylation: a ubiquitin-like modification. Trends Biochem. Sci. 49, 52–67 (2024).

Zhang, S., Yu, Q., Li, Z., Zhao, Y. & Sun, Y. Protein neddylation and its role in health and diseases. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 1–36 (2024).

Macek, B. et al. Protein post-translational modifications in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 651–664 (2019).

Pearce, M. J., Mintseris, J., Ferreyra, J., Gygi, S. P. & Darwin, K. H. Ubiquitin-like protein involved in the proteasome pathway of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 322, 1104–1107 (2008).

Cerda-Maira, F. A. et al. Molecular analysis of the prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) conjugation pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 1123–1135 (2010).

Imkamp, F. et al. Dop functions as a depupylase in the prokaryotic ubiquitin-like modification pathway. EMBO Rep. 11, 791–797 (2010).

Millman, A., Melamed, S., Amitai, G. & Sorek, R. Diversity and classification of cyclic-oligonucleotide-based anti-phage signalling systems. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1608–1615 (2020).

Jenson, J. M., Li, T., Du, F., Ea, C.-K. & Chen, Z. J. Ubiquitin-like conjugation by bacterial cGAS enhances anti-phage defence. Nature 616, 326–331 (2023).

Ledvina, H. E. et al. An E1–E2 fusion protein primes antiviral immune signalling in bacteria. Nature 616, 319–325 (2023).

Millman, A. et al. An expanded arsenal of immune systems that protect bacteria from phages. Cell Host Microbe 30, 1556–1569.e5 (2022).

Hör, J., Wolf, S. G. & Sorek, R. Bacteria conjugate ubiquitin-like proteins to interfere with phage assembly. Nature 631, 850–856 (2024).

Chambers, L. R. et al. A eukaryotic-like ubiquitination system in bacterial antiviral defence. Nature 631, 843–849 (2024).

Cury, J. et al. Conservation of antiviral systems across domains of life reveals immune genes in humans. Cell Host Microbe 32, 1594–1607.e5 (2024). This study describes an exploration of bacterial immunity systems in human genome yields novel pathways of cell-autonomous immunity.