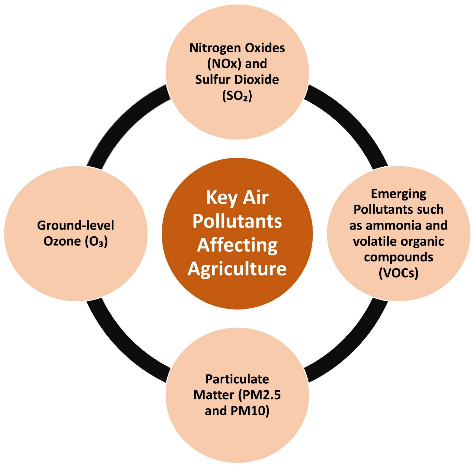

Air pollution has been conventionally framed as a public health crisis with evident links to respiratory and cardiovascular mortality. Moreover, its effects on agriculture and nutrition are increasingly being recognised as equally consequential. Pollutants such as ground-level ozone (O₃), fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) adversely affect plant physiology, crop yields, and nutrient composition, linking atmospheric degradation directly to food security and nutrition outcomes (fig 1). As global stressors intensify, especially with seasonal peaks such as the winter smog in northern India, understanding the hidden impacts on crop nutrition has become urgent.

Figure 1: Key pollutants impacting Agriculture & Food Security

Source: Bonface O. Monono et al., Air 2025, Vol 3

Air Pollution, Plant Physiology, and Crop Productivity

Air pollution affects plants through multiple interlinked pathways. Ground-level ozone, a powerful oxidant formed through photochemical reactions involving NOₓ and VOCs, infiltrates leaves and induces oxidative stress that damages chloroplasts, inhibits photosynthesis, and disrupts carbon assimilation pathways. Fine particles, particularly PM₂.₅, further reduce photosynthetically active radiation by scattering and absorbing sunlight, compounding the stress on crop growth.

Ground-level ozone, a powerful oxidant formed through photochemical reactions involving NOₓ and VOCs, infiltrates leaves and induces oxidative stress that damages chloroplasts, inhibits photosynthesis, and disrupts carbon assimilation pathways.

In a 2025 study utilising future climate scenarios, it was found that ozone pollution exacerbated by wildfires significantly reduces staple crop yields worldwide. This finding reinforces concerns that both episodic and background ozone levels will increasingly undermine agricultural output as global temperatures rise. The model suggests that, beyond chronic emissions from urban and agricultural sources, climate-driven fire events will exacerbate ozone exposure levels that impact crops. According to research conducted by the Centre for Ocean, River, Atmosphere and Land Sciences (CORAL) at IIT Kharagpur, surface ozone could reduce wheat yields by up to 20 percent by mid-century under high-emission scenarios, with rice and maize also experiencing significant declines. These projections reflect a growing consensus that ozone is a critical but under-recognised threat to staple crop productivity and thus to food security trajectories.

Nutritional Quality: Beyond Yield Loss to Nutrient Reduction

Yield reductions, while significant, only capture part of the impact of poor air quality on food systems. Emerging evidence indicates that exposure to pollutants, including O₃ and elevated CO₂, alters nutrient composition in crops, leading to nutritional dilution, which is the decrease in the concentration of nutritional elements in plant tissue. Elevated CO₂, a co-occurring pollutant in many agro-industrial regions, increases carbohydrate accumulation while diluting concentrations of protein, micronutrients such as zinc and iron, and essential phytochemicals. A large-scale synthesis of nearly 60,000 crop nutrient observations found that rising atmospheric CO₂ (already at ~425 ppm) is associated with measurable declines in micronutrient density and increased caloric content, thus raising hidden hunger risks even where caloric sufficiency persists.

Reviews of global air quality impacts note that pollutants interfere with enzymatic processes and soil microbial communities that are critical to nutrient availability and uptake.

Although systematic experimental data on ozone’s direct effects on nutrient profiles remain sparser, high ozone levels disrupt nitrogen metabolism in plant tissues, a key determinant of protein synthesis. It can also alter the allocation of micronutrients and secondary metabolites. Reviews of global air quality impacts note that pollutants interfere with enzymatic processes and soil microbial communities that are critical to nutrient availability and uptake. Field observations from studies on particulate deposition reveal that affected crops such as wheat and cotton exhibit a 20-40 percent reduction in chlorophyll content. This suggests broader metabolic disruptions that could lead to shifts in nutrient availability.

Crop residue burning, a practice prevalent in North India and elsewhere, exemplifies how agricultural activities both emit pollutants and suffer from their consequences. A recent World Health Organization (WHO) report indicates that agricultural air pollution from ammonia and stubble burning contributes to over 500,000 premature deaths globally each year, with 68,000 in India alone, highlighting the risks of agricultural emissions for both human health and crop environments. Beyond air quality, the practice degrades soil microbial biodiversity, increases pest pressures, and accelerates nutrient losses from farm ecosystems, reinforcing feedback loops that degrade crop quality and resilience.

Contextualising India’s Air Quality and Agricultural Risks

The Indian context illustrates the compounding nature of smog impacts on food systems. Northern India regularly experiences severe pollution episodes in winter; recent data show PM₂.₅ and Air Quality Index (AQI) peaking well above hazardous thresholds across Delhi and the National Capital Region, even after the typical farm fire season has ended, a pattern driven by transport emissions, household fuels, industrial sources, and ongoing agricultural residue burning. Despite some regional reductions in stubble burning reported in parts of Punjab and Haryana, spikes in emissions continue to elevate pollutant burdens in agricultural landscapes. Many policy interventions target urban air quality without sufficiently addressing rural and peri-urban emissions directly linked to food production, leaving a significant portion of pollutant exposure unmitigated.

Despite some regional reductions in stubble burning reported in parts of Punjab and Haryana, spikes in emissions continue to elevate pollutant burdens in agricultural landscapes.

While India’s experience is acute, analogous evidence emerges globally. Studies modelling the impact of air quality improvements in China suggest that reductions in ozone and PM₂.₅ could increase staple crop yields significantly, resulting in higher calorie production and stronger food security outcomes. Similarly, research in the United States indicates that rising background ozone levels have already caused around US$2.6 billion in annual agricultural losses across crops such as wheat, maize, and soybeans, reflecting a near-universal vulnerability of productive landscapes to air pollution.

Conclusion

The evidence underscores that air quality must be integrated into food and nutrition policy frameworks. Agricultural policy can also play a constructive role; for example, promoting zero-tillage and residue management technologies shows promise in reducing emissions from crop burning and thereby improving air quality while maintaining soil health and productivity. “Smog on our plates” is not metaphorical; it is an empirically grounded phenomenon with direct implications for crop yield, nutritional quality, and food safety. Recent evidence from atmospheric science, agronomy, and global synthesis studies affirms that poor air quality undermines both the quantity and quality of food supplies. As persistent smog events and chronic pollutant exposure become more common, especially in densely populated agrarian regions like India, systemic policy responses that integrate air quality, agriculture, and nutrition are essential to safeguard health and food security in an increasingly polluted world.

Shoba Suri is a Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.