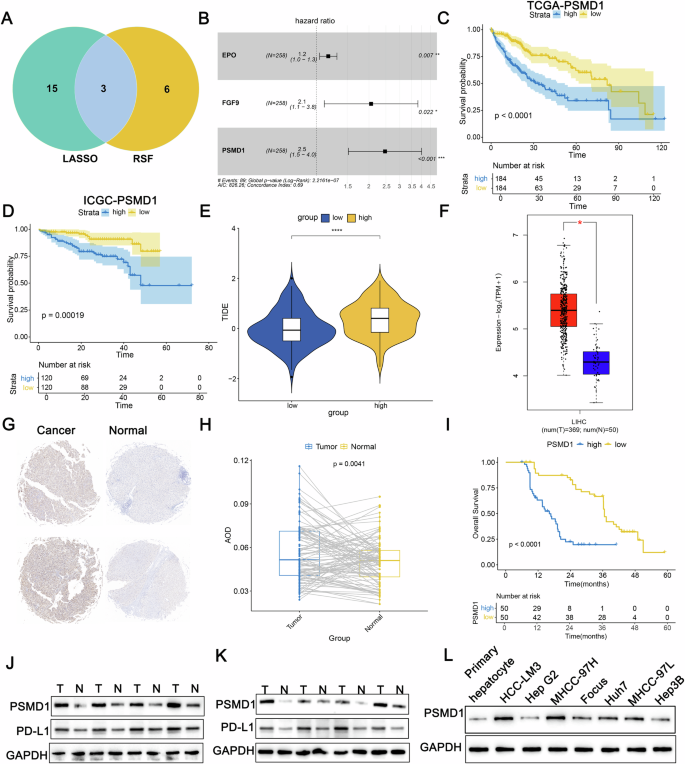

PSMD1 is an oncogene associated with HCC progression and clinical outcomes

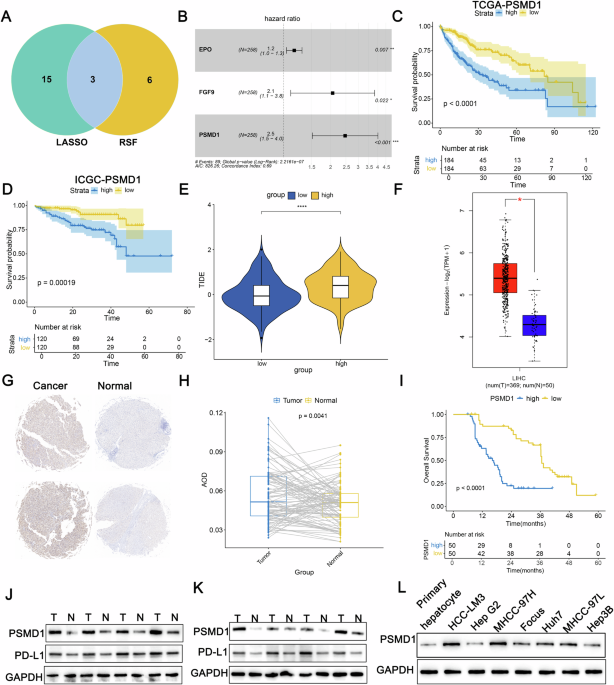

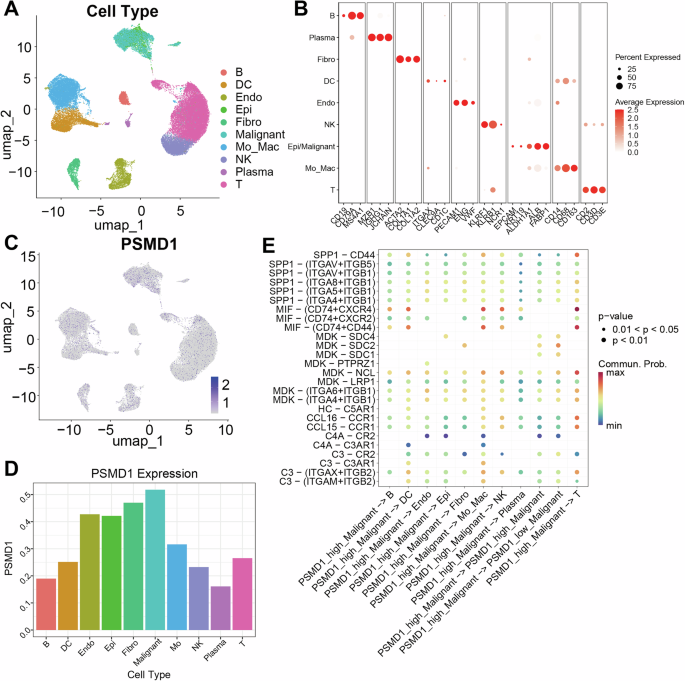

To explore the genetic factors underlying HCC progression and their influence on immune and targeted therapies, the TCGA dataset comprising 368 HCC cases was partitioned into two cohorts: 258 cases for training and 110 cases for validation, maintaining a 7:3 ratio. A univariate Cox regression analysis conducted on the training cohort identified 306 genes with prognostic significance. Subsequent LASSO regression narrowed this down to 18 pivotal genes (Fig. S1A, B). Additionally, random survival forest (RSF) analysis identified nine key genes (Fig. S1C). The overlap between these two methods highlighted three genes subjected to multivariate Cox regression analysis (Fig. 1A). Among these, PSMD1 presented the highest hazard ratio (HR = 2.50) (Fig. 1B). The cohorts were then stratified into high- and low-risk groups on the basis of their median risk scores. Survival analyses demonstrated that individuals in the high-risk group exhibited markedly reduced overall survival compared with their low-risk counterparts (Fig. 1C, D; Fig. S1D, E). The ESTIMATE algorithm revealed a greater degree of immune infiltration in the high-risk group (Fig. S1F–H). CIBERSORT analysis revealed an increased abundance of regulatory T cells and M0 macrophages in this group. In addition, TIDE analysis confirmed that the high-risk group exhibited elevated TIDE scores, indicating a poorer immunotherapeutic response (Fig. 1E). To further investigate the role of PSMD1 in HCC progression and its relationship with immunotherapy, a comprehensive analysis was conducted. Data from the TCGA database revealed significant overexpression of PSMD1 in HCC tissues (Fig. 1F). Immunohistochemical analysis of tissue microarrays from 100 patients, comprising both cancerous and adjacent noncancerous tissues, revealed elevated PSMD1 levels in HCC tissues (Fig. 1G, H). Patients exhibiting increased PSMD1 expression experienced notably reduced overall survival (Fig. 1I). Western blot validation confirmed the increased PSMD1 levels in the HCC samples (Fig. 1J, K). Previous studies have suggested that elevated PD-L1 expression on the cell surface can transform Th1 cells expressing T-box transcription factors into FOXP3+T regulatory cells in vivo, thereby amplifying immunosuppressive effects [12]. By integrating TIDE and CIBERSORT data, this study evaluated the expression patterns of PSMD1 and PD-L1 and revealed a concurrent increase in PD-L1 levels, which was consistent with PSMD1 upregulation in HCC tissues (Fig. 1J, K, S1J). Overall, PSMD1 overexpression in HCC tissues contrasted with its reduced expression in adjacent noncancer tissues. These findings prompted further analysis of PSMD1 expression in relation to the clinicopathological characteristics of 100 HCC patients. Higher PSMD1 expression levels were associated with larger tumor size (p = 0.005), advanced TNM stage (p = 0.015), and increased Edmondson grade (p = 0.005) (Table 1). As a biomarker highly expressed in HCC, PSMD1 holds promise for guiding therapeutic strategies and improving prognostic assessments in HCC patients.

Fig. 1: PSMD1 is an oncogene associated with HCC progression and clinical outcomes.

A Venn diagram showing overlapping genes identified by the LASSO and RSF methods. B A forest plot of OS was generated via multivariate Cox regression models. Kaplan–Meier curves of OS according to the risk score in TCGA-LIHC (C) and ICGC_LIRI_JP (D) cohorts. E Tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion (TIDE) scores for the prediction of immunotherapy response in the two groups. F Boxplot showing significant differences in PSMD1 mRNA levels between tumor and normal samples in the TCGA-LIHC cohort. G, H Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of PSMD1 protein levels in paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues. I The Kaplan–Meier survival curve for PSMD1 expression revealed that patients in the high-PSMD1 expression group had worse OS. J, K Protein expression levels of PSMD1 and PD-L1 in HCC tissues and corresponding adjacent tissues. L Protein expression levels of PSMD1 and PD-L1 in primary human hepatocytes and HCC cell lines. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

Table 1 Correlation between PSMD1 expression and clinicopathological features in HCC tissues (n = 100, χ2-test).Identification of the cellular localization and cell communication pathways associated with PSMD1

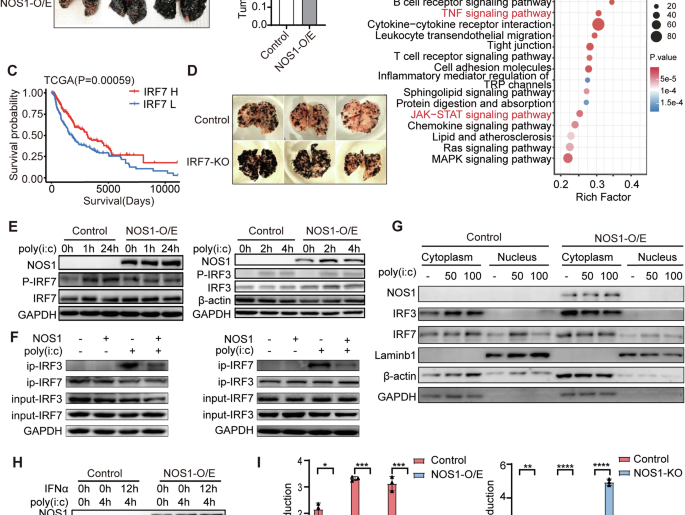

To further investigate the distribution and function of PSMD1 within the TME, we conducted a single-cell analysis. After performing quality control and filtering on the GSE149614 dataset, 49,431 cells were retained for subsequent analyses. Using classical cell markers, the cells were categorized into various types, including B cells, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, malignant tumor cells, monocytes/macrophages, NK cells, plasma cells, and T cells (Fig. 2A, B). PSMD1 expression was detected across all cell types, with the highest levels observed in HCC tumor cells (Fig. 2C, D). To explore the potential impact of PSMD1 expression in tumor cells on the tumor microenvironment, we conducted a cell communication analysis. We defined tumor cells exhibiting the top 10% of PSMD1 expression as PSMD1-high malignant cells, while the remaining tumor cells were classified as PSMD1-low malignant cells. Subsequent analysis utilizing the CellPhoneDB-secreted ligand‒receptor database revealed that tumor cells with high PSMD1 expression predominantly employ ligands such as MIF, MDK, and SPP1 as signaling molecules to communicate with immune cells within the microenvironment (Fig. 2E). In conclusion, PSMD1 plays an important role in the HCC microenvironment.

Fig. 2: Identification of the cellular localization and cell communication pathways associated with PSMD1.

A UMAP plots showing the identification of different clusters of cells in human HCC tumors. B Dot plots showing the specific cell markers for different cell types. UMAP plot (C) and bar plot (D) indicating PSMD1 expression across different cell clusters. E CellChat analysis revealed the probabilities of communication from high- and low-PSMD malignant cells to other cell clusters. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

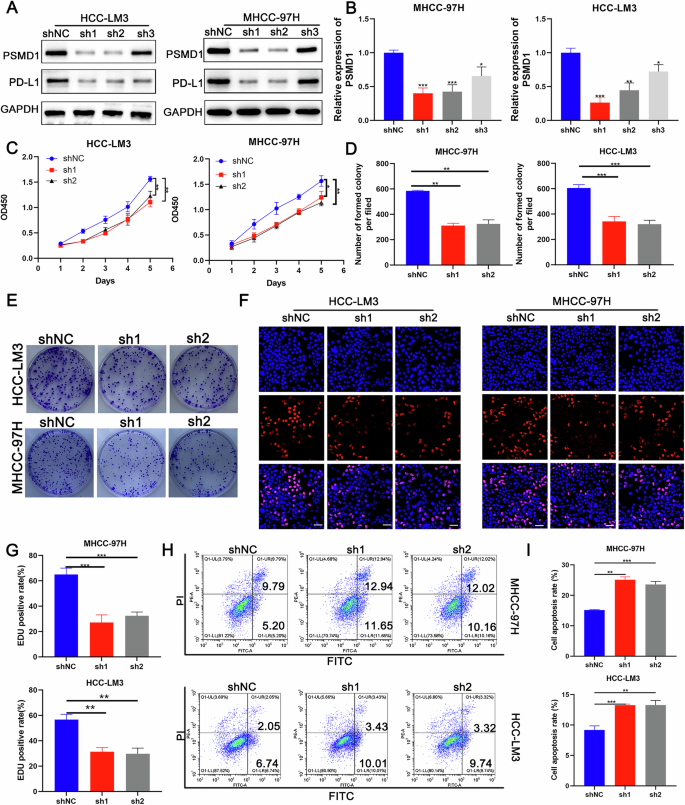

Inhibition of PSMD1 inhibits HCC proliferation and accelerates apoptosis in vitro

To investigate the role of PSMD1 in HCC progression, we conducted knockdown experiments in which PSMD1 was targeted in MHCC-97H and HCC-LM3 cell lines via shRNAs. Two specific shRNA sequences, referred to as sh1 and sh2, were employed to generate shPSMD1-1 and shPSMD1-2 constructs, respectively (Fig. 3A, B). The results from the CCK8 assays demonstrated that PSMD1 silencing resulted in a significant reduction in cell proliferation (Fig. 3C). Similarly, colony formation and EdU assays revealed a markedly lower average colony count in PSMD1-suppressed cells than in control cells (Fig. 3D, E). Furthermore, apoptosis assays revealed an increased apoptotic rate in HCC cells treated with PSMD1 shRNA (Fig. 3H, I). To further investigate apoptosis-associated proteins, their expression levels were analyzed via western blotting. BCL-2 expression was significantly lower in PSMD1-knockdown cells from both the HCC-LM3 and MHCC-97H lines than in control cells. Conversely, the expression of BAX was notably upregulated in these knockdown cells (Fig. S1K). Taken together, these results indicate that PSMD1 knockdown inhibits HCC cell proliferation while promoting apoptosis in vitro.

Fig. 3: PSMD1 inhibition inhibits HCC proliferation and accelerates apoptosis in vitro.

A Western blotting of PSMD1 and PD-L1 expression in HCC-LM3 and MHCC-97H cells transfected with shPSMD1. B MRNA expression of PSMD1 in HCC-LM3 and MHCC-97H cells transfected with shPSMD1. C A CCK-8 assay was used to determine the growth rate of PSMD1-knockdown HCC cells. D, E Colony formation assay for HCC cells. F, G An EdU assay was performed to evaluate the proliferation ability of HCC cells after PSMD1 was downregulated. Scale bar, 50 μm. H, I Cell apoptosis assays were performed in the PSMD1-knockdown groups. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

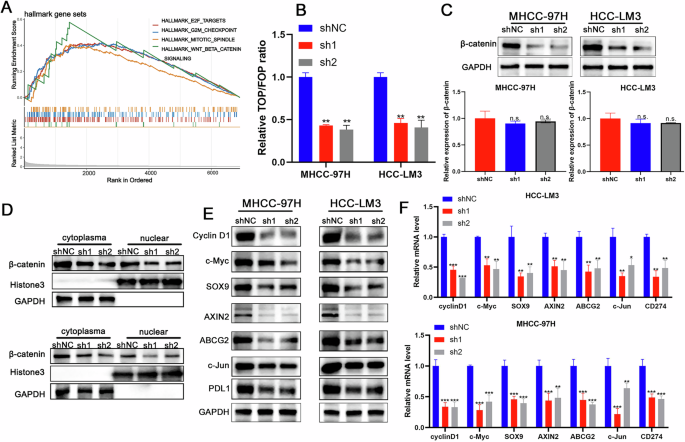

PSMD1 regulates the expression of PD-L1 through the β-catenin signaling pathway

To elucidate the signaling pathways associated with the biological function of PSMD1, GSEA was performed using data from single-cell databases. The analysis revealed a correlation between elevated PSMD1 expression and increased activity of the β-catenin signaling pathway (Fig. 4A). Prior studies have established that the WNT/β-catenin/TCF signaling cascade plays a pivotal role in regulating the development and progression of HCC [2]. Consistent with these observations, the β-catenin/Tcf4 transcriptional reporter (TOP/FOPFLASH) luciferase assay revealed a significant reduction in β-catenin transcriptional activity in HCC cells following PSMD1 knockdown (Fig. 4B). Further investigation into the effect of PSMD1 on β-catenin revealed no measurable changes at the mRNA level. However, PSMD1 knockdown markedly reduced the total β-catenin protein level (Fig. 4C). Fractionation experiments further confirmed notable alterations in the β-catenin protein distribution between the nucleus and cytoplasm upon PSMD1 silencing (Fig. 4D). These changes in β-catenin signaling were accompanied by reduced expression of β-catenin target genes, including CyclinD1, c-Myc, SOX9, AXIN2, ABCG2, and c-jun, in both MHCC-97H and HCC-LM3 cells (Fig. 4E, F). Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence that PSMD1 significantly regulates β-catenin protein expression, ultimately impacting PD-L1 expression. Taken together, these findings suggest that the aberrant expression of the PSMD1/β-catenin axis contributes substantially to HCC progression.

Fig. 4: PSMD1 regulates the expression of PD-L1 through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

A GSEA result showing the pathways enriched with PSMD1 expression in malignant cells. B The luciferase activity of β-catenin/Tcf4 transcriptional activity was measured in shPSMD1 and control HCC cells. C Protein and mRNA expression of β-catenin in HCC-LM3 and MHCC-97H cells transfected with shPSMD1. D Knockdown of PSMD1 decreased the protein levels of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin in HCC cells. E Knockdown of PSMD1 decreased the protein levels of CyclinD1, c-Myc, SOX9, AXIN2, ABCG2, c-jun, PD-L1 in HCC cells. F Knockdown of PSMD1 decreased the mRNA levels of CyclinD1, c-Myc, SOX9, AXIN2, ABCG2, c-jun, and PD-L1 in HCC cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

PSMD1 promotes tumor proliferation and inhibits apoptosis through the β-catenin pathway

On the basis of the hypothesis that β-catenin signaling operates downstream of PSMD1, a series of experiments was conducted to evaluate whether PSMD1 modulates β-catenin signaling during HCC progression. TOP/FOP reporter assays in HCC cells revealed that TOP/FOP luciferase activity was significantly reduced following sh1 transfection (Fig. S2A). However, this decrease in luciferase activity was reversed upon treatment with the Wnt/β-catenin agonist SKL2001 in MHCC-97H and HCC-LM3 cells (Fig. S2A). In addition, treatment of shPSMD1-transfected HCC cells with SKL2001 confirmed, via Western blot analysis, that β-catenin signaling was reactivated in the SKL2001-treated cells. This reactivation was accompanied by increased expression of β-catenin downstream targets, including Cyclin D1, c-Myc, SOX9, AXIN2, ABCG2, PDL1, and c-Jun (Fig. S2B). These findings suggest that PSMD1 knockdown significantly suppresses β-catenin signaling activity. In support of this hypothesis, SKL2001 effectively rescued the proliferative ability of HCC cells inhibited by PSMD1 knockdown, as demonstrated by CCK-8, colony formation, and EdU assays (Fig. S2C–G). Additionally, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that SKL2001 treatment attenuated apoptosis in HCC cells with shPSMD1 knockdown (Fig. S3A, B).

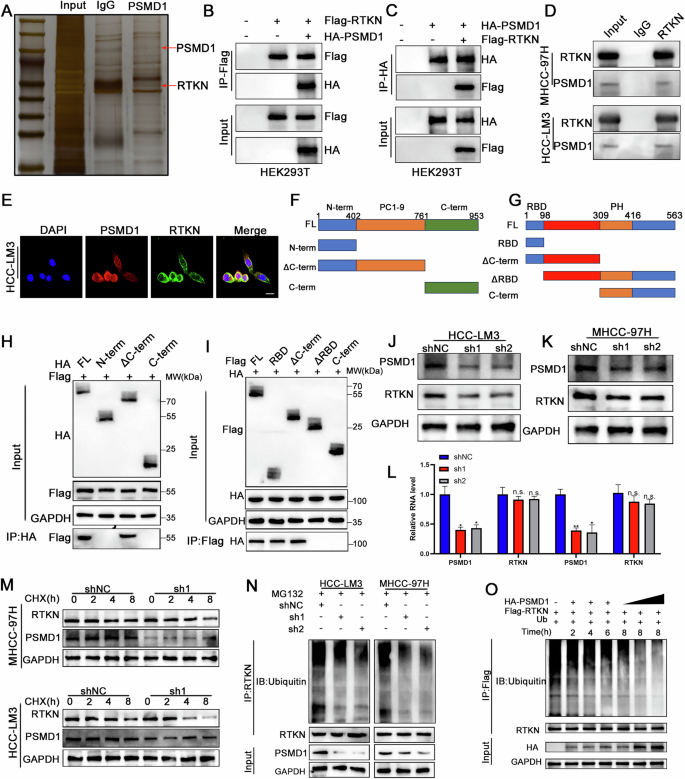

PSMD1 binds RTKN and inhibits its degradation in HCC cells

To investigate the specific mechanisms by which PSMD1 contributes to β-catenin, we performed coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) followed by mass spectrometry (IP–MS) to identify potential targets of PSMD1 (Fig. 5A). Using IP‒MS analysis, we identified 116 distinct proteins (Table S1) and found that PSMD1 interacts with RTKN rather than directly binding to β-catenin (Fig. S3C). Notably, RTKN has been previously reported to increase β-catenin transcription [13]. To verify the interaction between these proteins, HEK293T cells were transfected individually or together with Flag-RTKN or HA-PSMD1, followed by detection with specific antibodies (Fig. 5B, C). Similarly, we confirmed that these proteins physically interact within HCC cells (Fig. 5D; Fig. S3D). Immunofluorescence staining revealed that PSMD1 (red) and RTKN (green) colocalized in the cytoplasm of HCC cells (Fig 5E and S3E). Additionally, to identify the minimal essential region necessary for their interaction, various RTKN and PSMD1 deletion mutants were co-expressed in HEK293T cells. As shown in Fig. 5F–I, the direct interaction is facilitated by the RBD domain of RTKN (amino acids 1–98) and the PC1–9 domain of PSMD1 (amino acids 402–761), which are necessary and sufficient. Interestingly, PSMD1, a component of the UPS (proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase 1), has been shown to inhibit the ubiquitination of target proteins [10]. Knockdown of PSMD1 dramatically reduced RTKN protein expression (Fig. 5J, K). In addition, the mRNA expression level of RTKN did not significantly change with PSMD1 knockdown (Fig. 5L). Similarly, after treatment with cycloheximide (CHX), PSMD1 knockdown facilitated the degradation of endogenous RTKN, suggesting that PSMD1 prolongs the half-life of the RTKN protein (Fig. 5M). We found that the knockdown of PSMD1 significantly reduced RTKN ubiquitination in HCC cells (Fig. 5N). In vitro ubiquitylation assays revealed that PSMD1 inhibited the ubiquitination of RTKN in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5O). Taken together, these results indicate that PSMD1 is a regulator of RTKN and a prognostic marker.

Fig. 5: PSMD1 binds RTKN2 and inhibits its degradation in HCC cells.

A Silver-stained SDS‒PAGE gel containing proteins derived from IP by PSMD1 and IgG. B, C A co-IP assay was performed in HEK293T cells. D A co-IP assay was performed in HCC cells. E Immunofluorescence analysis revealed the colocalization of RTKN (green) and PSMD1 (red) in HCC-LM3 cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. F Schematic drawing of full-length PSMD1 and truncations. G Schematic drawing of full-length RTKN and truncations. H, I Co-IP assays were performed in HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-RTKN and HA-PSMD1 truncations. J, K Knockdown of PSMD1 decreased the protein level of RTKN. L Knockdown of PSMD1 does not decrease the mRNA level of RTKN. M Western blot analysis of RTKN in MHCC-97H and HCC-LM3 cells treated with CHX. N Ubiquitination of RTKN proteins in HCC cells was determined via co-IP and western blotting. O PSMD1 inhibits the ubiquitination of RTKN in a time- and dose-dependent manner. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

PSMD1 regulates the progression of HCC in an RTKN-dependent manner

Studies have reported that RTKN plays a role in promoting tumor progression in gastric cancer and HCC [14, 15]. Therefore, we hypothesize that PSMD1 may exert its biological functions through RTKN. To test this hypothesis, we further validated this observation using database analysis. Examination of RTKN expression in the TCGA database demonstrated significantly higher expression in HCC tissues compared to adjacent non-cancerous tissues. (Fig. S4A). Moreover, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the TCGA dataset revealed that elevated RTKN expression was associated with poorer overall survival (OS) in HCC patients, consistent with its elevated expression levels in tumor tissues (Fig. S4B). We next investigated whether PSMD1 regulates HCC progression through an RTKN-dependent mechanism. WB and RT-qPCR analyses confirmed the transfection efficiency of the RTKN plasmid, and we observed that RTKN does not affect the expression of PSMD1 (Fig. S3F, G). Consistent with our hypothesis, RTKN overexpression reversed the reduction in β-catenin caused by PSMD1 knockdown (Fig. S4C). Additionally, RTKN effectively rescued the suppression of HCC cell proliferation induced by PSMD1 knockdown, as evidenced by the results of the CCK-8, colony formation, EdU proliferation (Fig. S4D–H; Fig. S5A). Moreover, flow cytometry analysis revealed that RTKN overexpression significantly decreased apoptosis in PSMD1-knockdown HCC cells (Fig. S4I, J). Collectively, these findings suggest that RTKN overexpression modulates the tumor-inhibitory effects of PSMD1 knockdown in HCC.

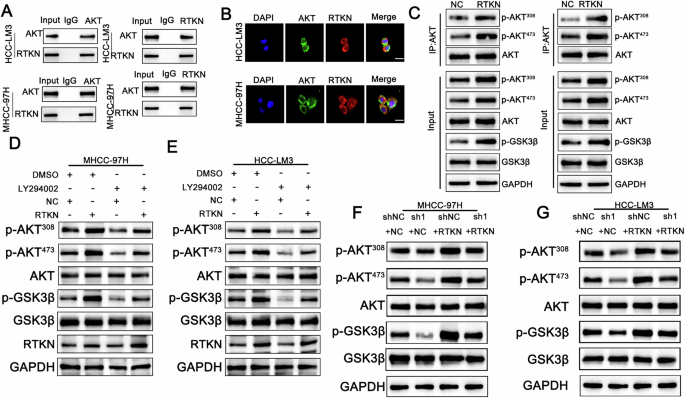

RTKN binds to AKT and promotes its phosphorylation

To further explore the impact of RTKN on the transcriptional regulation of β-catenin, we conducted immunoprecipitation using RTKN as a probe, followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. The MS results identified AKT as an interacting protein (Fig S5B). Subsequent coimmunoprecipitation assays confirmed the interaction between AKT and RTKN (Fig. 6A). Immunofluorescence colocalization revealed that both proteins were present in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 6B). Western blot analysis revealed that phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT) levels were elevated in RTKN-overexpressing cells, accompanied by an increase in phosphorylated GSK3β (p-GSK3β) levels. (Fig. 6C). These findings suggest that RTKN activates the AKT signaling pathway. To evaluate whether AKT contributes to tumor progression through the PI3K/AKT pathway, we treated RTKN-overexpressing cells with LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor. Prior to treatment, LY294002 administration did not alter RTKN expression levels (Fig. 6D, E). Western blot analysis revealed that the elevated levels of phosphorylated AKT and phosphorylated GSK3β in RTKN-overexpressing cells were effectively reduced upon additional treatment with LY294002 (Fig. 6D, E). Moreover, these experiments further revealed that PSMD1 knockdown suppressed AKT phosphorylation, an effect that was reversed by RTKN overexpression (Fig. 6F, G). Overall, PSMD1 may influence AKT and GSK3β phosphorylation by modulating RTKN ubiquitination and protein interactions. These results highlight the role of PSMD1 in regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis in HCC, likely via the β-catenin pathway.

Fig. 6: RTKN binds to AKT and promotes its phosphorylation.

A A co-IP assay was performed in HCC cells. B Immunofluorescence analysis revealed the colocalization of AKT (green) and RTKN (red) in HCC-LM3 and MHCC-97H cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. C HCC cells stably transduced with negative control or RTKN plasmids and lysates were immunoprecipitated with AKT and immunoblotted for p-AKT473, p-AKT308, GSK3β, p-GSK3β and AKT. D–G The protein expression of AKT, phosphorylated AKT, GSK3β and p-GSK3β was assessed in the indicated cell lines. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

PSMD1 promotes the growth of HCC in vivo

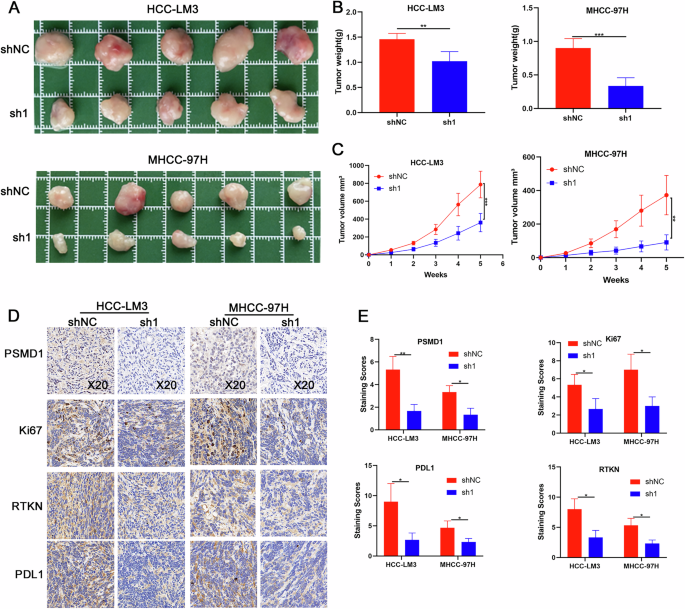

To investigate the tumor-promoting function of PSMD1 in HCC in vivo, we generated subcutaneous tumor xenograft models in BALB/c nude mice via PSMD1-knockdown MHCC-97H and HCC-LM3 cells. As shown in Fig. 7A–C, PSMD1 knockdown significantly inhibited tumor growth and decreased tumor weight in the xenograft mouse models. To further confirm the in vivo effects of PSMD1 knockdown, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed. Compared with control tumors, PSMD1-knockdown tumors presented a marked reduction in Ki67 expression, indicating a decrease in cell proliferation. Additionally, the IHC results demonstrated a substantial decrease in RTKN and PD-L1 protein expression following PSMD1 knockdown (Fig. 7D, E). Collectively, these findings highlight the inhibitory effect of PSMD1 knockdown on tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 7: PSMD1 promotes the growth of HCC in vivo.

A PSMD1 knockdown suppressed the growth of HCC xenografts in nude mice. B, C Tumor size and weight of the subcutaneous tumor growth model injected with HCC cells (5 mice/group). D IHC staining of the indicated proteins in tumor samples obtained from the subcutaneous tumor growth model. E IHC staining scores of xenograft tumors. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

Low expression of PSMD1 enhanced the antitumor efficacy of anti-PD1 therapy in vivo

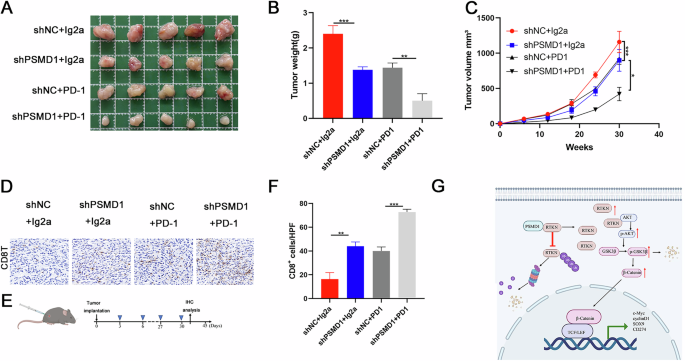

To investigate whether PSMD1 knockdown enhances the sensitivity of HCC to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, orthotopic HCC mouse models were established with PSMD1-knockdown or control Hep1-6 cells (Fig. S5C). The mice were treated with either an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) or IgG as a control (Fig. 8A). Tumor growth was significantly inhibited by both PSMD1 knockdown and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Notably, the combination of these two treatments achieved the most pronounced therapeutic effect (Fig. 8A–C). Mechanistically, anti-PD-L1 therapy exerts its antitumor effects predominantly by enhancing T-cell functions. The efficacy of this combined treatment was further validated by CD8⁺ T-cell staining in xenograft tumor tissues (Fig. 8D–F). In summary, our findings provide strong evidence that PSMD1 knockdown potentiates the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in HCC, highlighting PSMD1 as a potential therapeutic target.

Fig. 8: Low expression of PSMD1 enhanced the antitumor efficacy of anti-PD1 therapy in vivo.

A Photographs of mouse tumors from each group (5 mice/group). B, C Tumor size and weight of the subcutaneous tumor growth model injected with HCC cells (5 mice/group). D IHC staining showing CD8 expression in HCC tissues. E Flow chart of the animal model. F Percent of CD8+ cells detected via IHC staining. G Proposed working model. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.