Boston University nutrition professors reacted negatively to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ updated dietary guidelines, saying the pyramid is flawed in its messaging, accuracy and clarity.

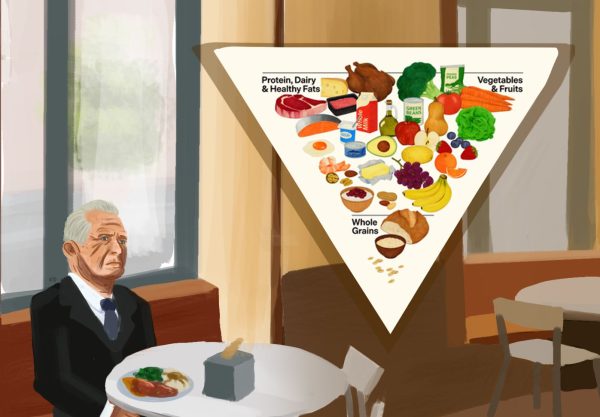

HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. released new dietary guidelines for 2025-2030 on Jan. 7. The new guidelines bring back the pyramid-style infographic where previous departments promoted MyPlate, which displays recommended portion sizes for each food group.

The nutritional pyramid was phased out in 2011 for its confusing nature. The new style RFK Jr. released flips the old one upside down, encouraging people to eat less grains and more protein and fats.

Maura Walker, an assistant professor of nutrition at BU, said because of the pyramid’s “aggressive” messaging and lapses in accuracy, it doesn’t “serve the public well at all.”

“There’s quite a bit of places that aren’t detailed enough, and even just really blatant errors, but there is a lot of consistencies [to previous years],” Walker said. “Pushing it in this divisive way is going to really do nothing but promote not trusting scientists and policymakers.”

In addition to being a resource for healthcare professionals, the guidelines will dictate what food is served in public schools and other federally funded meal programs. Since BU is a private university, it will not be forced to comply.

In an email to The Daily Free Press, BU Dining Service’s director of marketing Lynn Cody wrote the department’s meal offerings are “thoughtfully designed” to meet students’ varying needs.

“BU Dining will continue to partner closely with the Sargent Choice Nutrition Center on menu development to ensure our offerings support students. Student feedback also helps shape our menus, and we’ll continue to rely on that input as we evolve the dining program,” Cody wrote.

The guidelines are in line with RFK Jr.’s Eat Real Food campaign, which argues the U.S. chronic disease emergency is in part due to the “Standard American Diet—a diet which, over time, has become reliant on highly processed foods,” the policy reads.

Walker said the lack of a scientific definition for processed food is going to make it challenging for consumers and federal food programs to adhere to.

Joan Salge Blake, a clinical professor of nutrition at BU, said one’s diet impacts their long-term health.

“What you eat and drink really increases or decreases your risk for many of the chronic diseases of Americans: heart disease, certain cancers, stroke and type two diabetes,” Salge Blake said.

However, evidence suggests most people haven’t followed the guidelines before and will continue to ignore them, Walker said.

One factor that could have made the policy more digestible for consumers is an example of how to meet the requirements it suggests, Salge Blake said.

For example, the new policy recommends children under the age of 11 avoid all added sugars. However, whole-grain bread, which is also recommended, is made with sugar, she said.

“There’s a little bit of miscommunication on how to [meet the recommendations] based upon these guidelines,” Salge Blake said. “You need more guidance on how … you’re going to make these changes.”