Studies on how plants respond to drought conditions are well-known, but their recovery has been understudied.

SAN DIEGO — In the face of climate change and growing drought concerns, there is new research that is shining a light on an immune response in plants that could be key to harvesting drought-resistant crops in the future.

Studies on how plants respond to drought conditions are well-known, but their recovery has been understudied.

Researchers at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, including Joseph Ecker, PhD, examined drought conditions in the flowering plant, Arabidopsis Thaliana, which is commonly used in plant research. The leaves dried up, became discolored and showed signs of drought stress.

“These are actually the plants we’re interested in here because we’ve mutated the gene and it can’t recover anymore,” Ecker said, as he compared the difference between the drought-stricken leaves of the lab plants to those that were lusher and greener in appearance.

With a focus on drought recovery, the quick response from plants when water is reintroduced and the gene reaction was astonishing to the researchers.

“It was a surprise to us that the genes that are involved in the recovery process are very rapidly induced within 15 minutes; thousands of genes are increased, and they are not the same genes that are going down during the drought process itself. It’s a completely new set of genes,” Ecker said.

It’s not just that the plants were thirsty. When absorbing the water, the immune system of the plants became the main priority. This plant gene response is believed to prevent infection from harmful bacteria during that recovery period, in which the plant’s health is more vulnerable.

“They are turning on pathways that we actually began to test. And sure enough, those plants are activating genes to protect itself,” Ecker said.

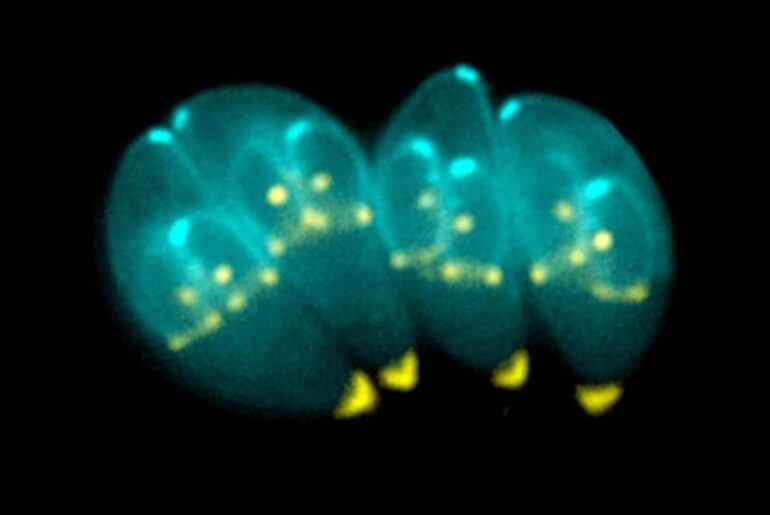

To see this reaction requires a deeper look at the plant leaf, or section of that leaf, using advanced gene-sequencing technology, including single-cell and spatial transcriptomic techniques. This technology captures gene expression patterns highlighted between microscopic cells.

“That diversity and in the different conditions, it does something completely different. These are like the first times we can really see the expression of a gene within the actual location within a leaf,” Natanella Illouz-Eliaz, a postdoctoral researcher in Ecker’s lab, said.

This immune response is referred to as Drought Recovery-Induced Immunity (DRII) by researchers.

“If we can now understand the function of these genes in this reference plant, we can then translate that information into a variety of crop plants,” said Ecker.

From the lab to the field, the ultimate goal of this research is to use this plant gene response for the broad concept of engineering nutritious crops that are resistant to drought conditions due to climate change.

“If we can really understand how plants are recovering from that mild drought, then we can really understand when you’re pushing them too far, and we can make them more resistant,” said Ecker.

This same immune response also took place in wild and domesticated tomato plants. Many of the genes that make up the lab plants are shared in various plant species, including agricultural crops like wheat and rice.

“We will look into gene expression in every cell type of the leaf tissue, of the crown tissue, and of the root tissue to have a very comprehensive understanding of how each gene is expressed during drought and recovery,” said Illouz-Eliaz.

The plant she is referencing is Sorghum. It is an important multi-purpose cereal crop used globally for flour in baked goods, sweeteners, and grain bowls. It is also drought-tolerant, so its gene response will help expand this research.

“If we understand the recovery process, it may help us help the plants to recover better,” Ecker said.