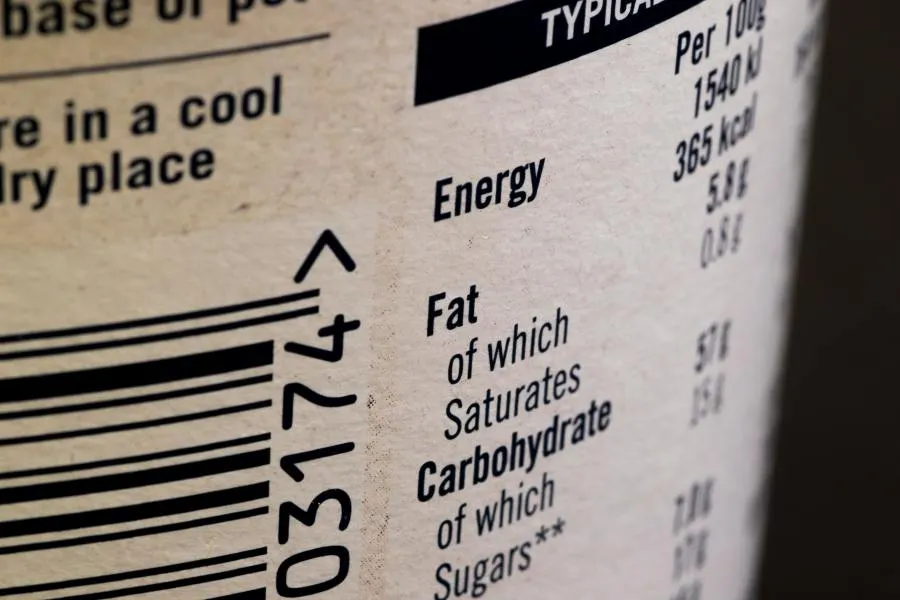

New research is suggesting that the Nutrition Info Box, proposed last year by the US FDA, may only be useful to consumers with high nutrition literacy. The front-of-package (FOP) label would contain information on saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars.

Unhealthy diets are increasing the risk of diseases and death globally. However, diets in the US remain poor quality and cost US$50 billion in annual health care costs, according to the researchers.

To address this issue, the FDA proposed implementing a nutrition info box in January last year. It includes amounts of saturated fats, sodium, and added sugar, which the research indicates may be too complicated to be easily interpreted by all US citizens.

The scientists conducted an online randomized trial including more than 5,000 participants. The respondents were the household’s main grocery shoppers, with varying levels of nutrition literacy and from different ethnic, racial, educational, and income groups.

“The FDA’s internal research suggests the ‘Nutrition Info Box’ label improves consumer understanding more than other label designs, and they hope it will help consumers quickly and easily identify healthier foods. We were interested in whether this label had different effects for people in different subgroups,” says first author of this study, Yuru Huang, assistant professor at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, US.

Comparing labels

Random images of foods and beverages were shown to participants, with six types of labels. It included one similar to the FDA’s proposed Nutrition Info Box, a “spectrum” label rating foods from least to most healthy, and other internationally used labels.

Random images of foods and beverages were shown to participants, with six types of labels.The participants were then asked to compare two types of labels and rate which they deemed healthier.

Random images of foods and beverages were shown to participants, with six types of labels.The participants were then asked to compare two types of labels and rate which they deemed healthier.

“For each of the labeling systems, we measured the gap in understanding between people with higher and lower nutrition literacy — that is, how much better consumers with higher nutrition literacy were at identifying healthier products compared to consumers with lower nutrition literacy,” says lead investigator Anna Grummon, assistant professor of pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine, US.

The researchers found that the spectrum labels were the easiest for consumers across all literacy levels to understand. Meanwhile, the nutrition literacy gap was at its largest with the Nutrition Info labels — resembling the one the FDA suggests.

“We were surprised to find that the Nutrition Info labels worked so much better for consumers with higher nutrition literacy compared to lower nutrition literacy,” says Grummon.

The study has been published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Urging to reconsider

Jason Block, a general internal medicine physician and associate professor in population health medicine at Harvard Medical School, US, stresses that there are two important considerations for the FDA before it finalizes its new label design.

“First, if the FDA requires a Nutrition Info label, they should ensure that they also provide extensive education to consumers with lower nutrition literacy about how to use it, to ensure that all consumers can benefit from this label.”

The researchers note that the labels demonstrate an overall improvement in consumer understanding.“Second, the FDA might consider adopting a different design other than the Nutrition Info label that avoids widening gaps in consumers’ ability to identify healthier products,” he adds. Block is also the principal investigator of the grant funding the study.

The researchers note that the labels demonstrate an overall improvement in consumer understanding.“Second, the FDA might consider adopting a different design other than the Nutrition Info label that avoids widening gaps in consumers’ ability to identify healthier products,” he adds. Block is also the principal investigator of the grant funding the study.

The researchers note that all the labels demonstrate an overall improvement in consumer understanding compared to current systems, such as numeric or voluntary labeling systems.

The results indicate that implementing such an FOP labeling system supports the FDA’s efforts but does not necessarily translate into consumers choosing healthier food products.

“In our previous research, we found that Nutrition Info labels did not lead consumers to choose healthier foods and beverages when grocery shopping, even though the labels helped consumers identify healthier products. In that study, the spectrum labels were the only labeling system to prompt healthier food purchases,” says Grummon.

Huang adds: “FOP labels may be more effective at prompting behavior change when they communicate a single, simple message and incorporate both positive and negative cues.”

“Our results show that the label effects vary across nutrition literacy levels, which could help inform the FDA about potential disparities before finalizing its label choice,” concludes Huang.