Participants and study design

This is a cross-sectional study as part of the “Schoolchildren Health Assessment Survey” (PASE, in Portuguese), which enrolled a representative sample of children aged 8 and 9 years, from all public and private schools in the urban area of Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Sample size was calculated using Epi Info software (version 7.2; Atlanta, GA), from a specific formula for cross-sectional studies. We considered the total number of schoolchildren in Viçosa aged 8 and 9 years (n = 1464) in 2015 [20], expected prevalence of 50% [21], tolerated error of 5%, and 95% confidence level for the calculation of sample size (n = 305). We added 15% for losses, resulting in a minimum sample of 351 children.

The schoolchildren were selected by stratified random sampling. The sample from each school met the proportionality ratio of students enrolled by age and sex. The selection of children was done by a random simple draw until the necessary number for each school was completed.

Non-inclusion criteria were considered as health problems that affected the children’s nutritional status or body composition, chronic use of medication that influenced glucose and/or lipid metabolism, or failure to contact primary care providers after three attempts.

A pilot study was made with 37 children aged 8–9 years enrolled in a school selected randomly. These children did not participate in the final sample. The pilot study was carried out to test the questionnaires.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV) (process no. 663.171/2014). All parents or guardians of children signed the Informed Consent Form.

Biochemical assays

In a 12-h fast, the blood samples were collected by venipuncture in the antecubital region at the UFV Health Center’s clinical analysis sector. The biochemical components of MetS (HDL-c, TG, fasting glucose, and insulin), markers of inflammation (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and adipokines (leptin and adiponectin), and pro- (malondialdehyde—MDA and SUA) and antioxidants (superoxide dismutase—SOD and ferric reducing antioxidant power—FRAP) were evaluated.

HDL-c, TG, fasting glucose, uric acid, and hs-CRP were measured in serum using automatic equipment (BioSystems 200 Mindray® model, Nanchan, China), according to the recommendations of the manufacturer of the Bioclin® kit used (Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil).

Fasting insulin was determined by the chemiluminescence immunoassay method and quantified by the Elecsys Insulin® test (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated according to the equation: fasting insulin (μU/mL) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)/22.5 [22].

Serum leptin was measured by the enzyme immunoassay method, with a coefficient of variation intra-assay <13.3% and inter-assay <12.7% (KAP2281, DIAsource®, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium). Plasma adiponectin was determined by commercial ELISA sandwich kits, with coefficients of variation intra-assay <10% and inter-assay <12% (human adiponectin: SEA605Hu, Cloud Clone Corp.®, Houston, TX, USA). Adipokines were analyzed in duplicate.

For the determination of oxidative residues, the measures were made in triplicate in plasma. SOD dosage was based on the rate of pyrogallol autoxidation (ACS reagent, 254002, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); MDA in the measurement of thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS); and FRAP was based on the ability of antioxidants to reduce ferric iron (Fe3 + ). The analysis was performed in polystyrene microplates using the FRAP solution. Trolox solution (97%, 238813, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as an antioxidant agent to determine the standard curve and the reading was performed on a Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 570 nm (SOD), 535 nm (MDA), 594 nm (FRAP). Analyzes were obtained on the standard curve.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured three times using digital blood pressure monitors (Omron®, Vernon Hills, IL, USA), with the child in a sitting position after resting for at least 5 min. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated [MAP = 1/3(SBP) + 2/3(DBP)] from systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressures’ mean, in mmHg [23].

MetS and components scores

There is no clear definition of MetS in children, and a continuous MetS score has been estimated using criteria similar to those for adults [24, 25]. It was recommended that the five main variables of MetS be used to calculate the score in research, including (1) central obesity (measured by waist circumference—or BMI and/or skinfold thickness if waist circumference is not available), (2) low HDL-c, (3) elevated triglycerides, (4) elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic and/or MAP), and (5) abnormal glucose metabolism (impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and/or HOMA-IR) [24]. In this study, waist circumference (WC) was used to assess central obesity and was measured with the use of an inelastic measuring tape, midway between the inferior margin of the ribs and the superior border of the iliac crest [26]. MAP was used as a criterion for assessing arterial pressure, and HOMA-IR as a measure of insulin resistance [25].

We calculated Z scores for WC, serum TG and HDL-c, HOMA-IR, and MAP by regressing each log-transformed component on sex and log-transformed age in linear regression models to obtain standardized residuals. After the HDL-c score was multiplied by -1, the overall score was calculated as the average of the five component scores. Higher values correspond to a worse metabolic profile [24, 25]. We also evaluate the standardized residuals for each of the five MetS components.

Normal-weight obesity (NWO) phenotype

NWO phenotype was identified when the child had a normal weight, according to BMI-for-age, and high body fat, simultaneously [27].

BMI-for-age z score was calculated by weight (kilograms) divided by the square of height (meters), according to sex, for the classification of nutritional status through the WHO AnthroPlus software [28]. Body fat (%) was assessed using the Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) method (Lunar Prodigy Advance, GE Medical Systems Lunar, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The high percentage of body fat was defined as values equal to or greater than 25% and 20% for girls and boys, respectively [29].

In this study, children with: 1. thinness (n = 12) were excluded; 2. normal-weight and adequate body fat percentage (n = 176) were classified as NWL; 3. normal-weight and high body fat (n = 66) were classified as NWO phenotype; and 4. overweight (n = 65) and obesity (n = 59) were grouped into the excess weight group. Considering the limitations of BMI in differentiating body tissues, two children with excess weight and adequate body fat percentage were excluded from the analyses in the group with excess weight, since all children in this group presented excessive body fat percentage.

Covariates

Information on the child’s age (years), sex (female and male), screen time (hours/day), and per capita family income (USD) was filled out in a semi-structured questionnaire during an interview with the child and their guardian. Screen time (spent on screen activities such as video games, computer, television, cell phone, or tablet) higher than 2 hours/day was defined as sedentary behavior [30]. Caloric intake was assessed using the average number of calories ingested from three 24-h recalls administered to the study volunteers.

Data analysisExposure

Obesity phenotypes (NWL, NWO, and excess weight).

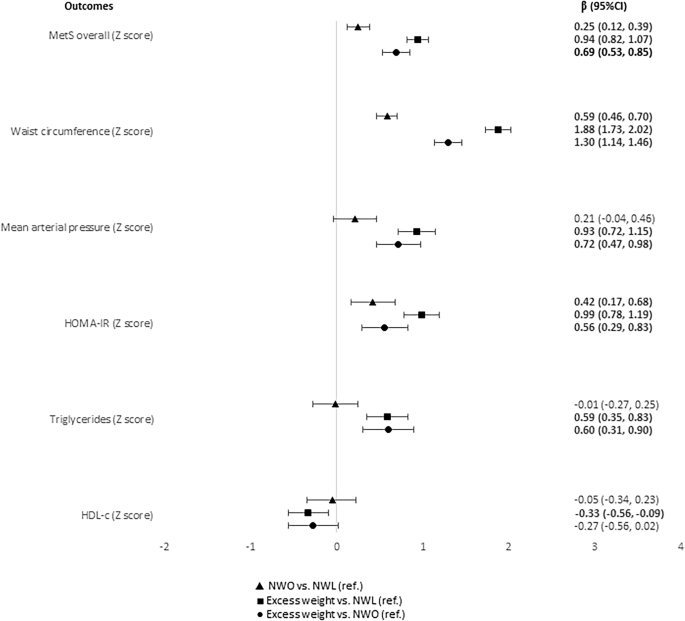

Outcomes

MetS and components scores (MetS overall, WC, MAP, HOMA-IR, TG, and HDL-c in Z score), anti- and inflammatory markers (adiponectin, CRP, and leptin), anti- and oxidative status (FRAP, SOD, MDA and SUA).

Covariates

Sex, age, per capita income, screen time, and caloric intake.

Statistical analyses

The consistency and distribution of numerical variables were evaluated by histograms, and skewness and kurtosis coefficients; the Shapiro-Wilk was used for the normality test. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies; numerical variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IR). Statistical differences for numerical variables according to the categories of obesity phenotypes were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (with Bonferroni post-hoc test) or Kruskal-Wallis (with Dunn post-hoc test). Statistical differences for categorical variables were calculated by the chi-square test for trend.

Multiple linear regression with robust estimates of the variance, which are consistent to heteroskedasticity and non-normality [31], were performed to evaluate the associations of the obesity phenotypes with MetS and its components scores, inflammatory markers, and anti- and oxidative markers. Independent models for each outcome variable were estimated. Coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, adjusted by sex, age, per capita income, screen time and caloric intake. The adjustment variables were defined by theoretical and statistical criteria [32]. In addition, the p for trend was calculated. All analyses were performed in the Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The statistical significance level was set to 5%.