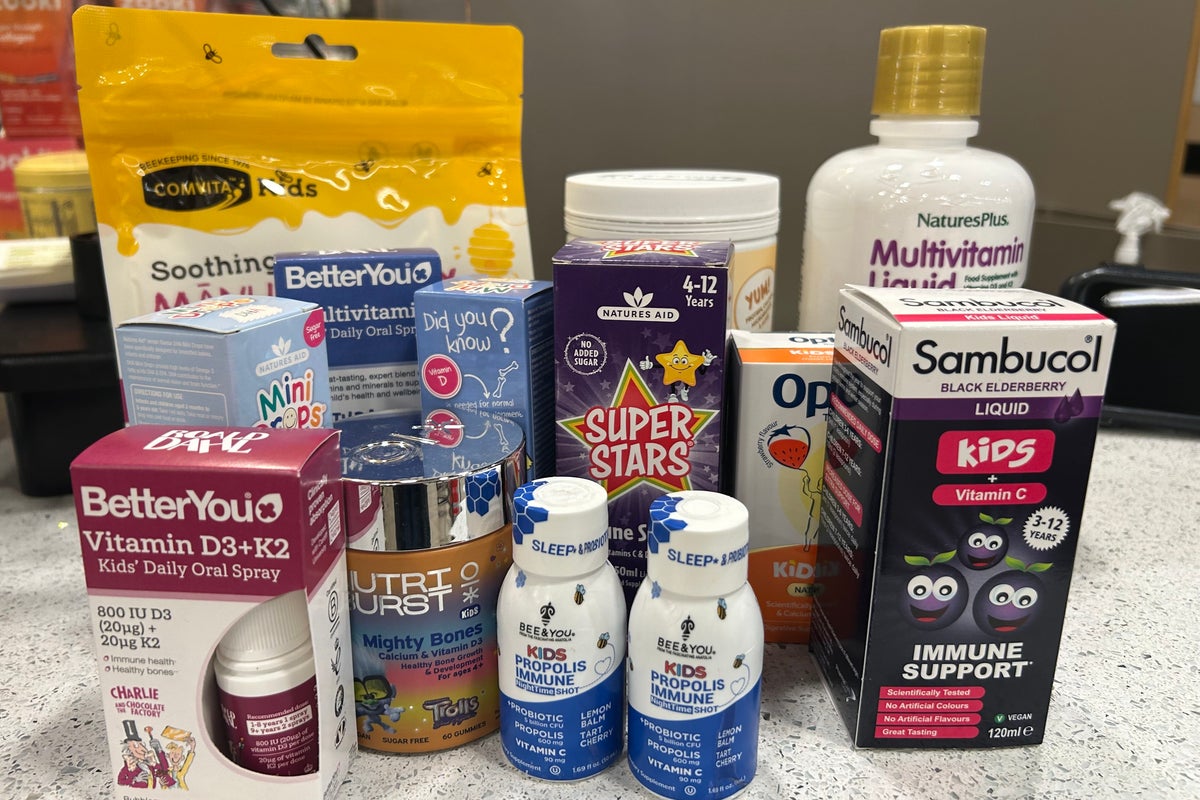

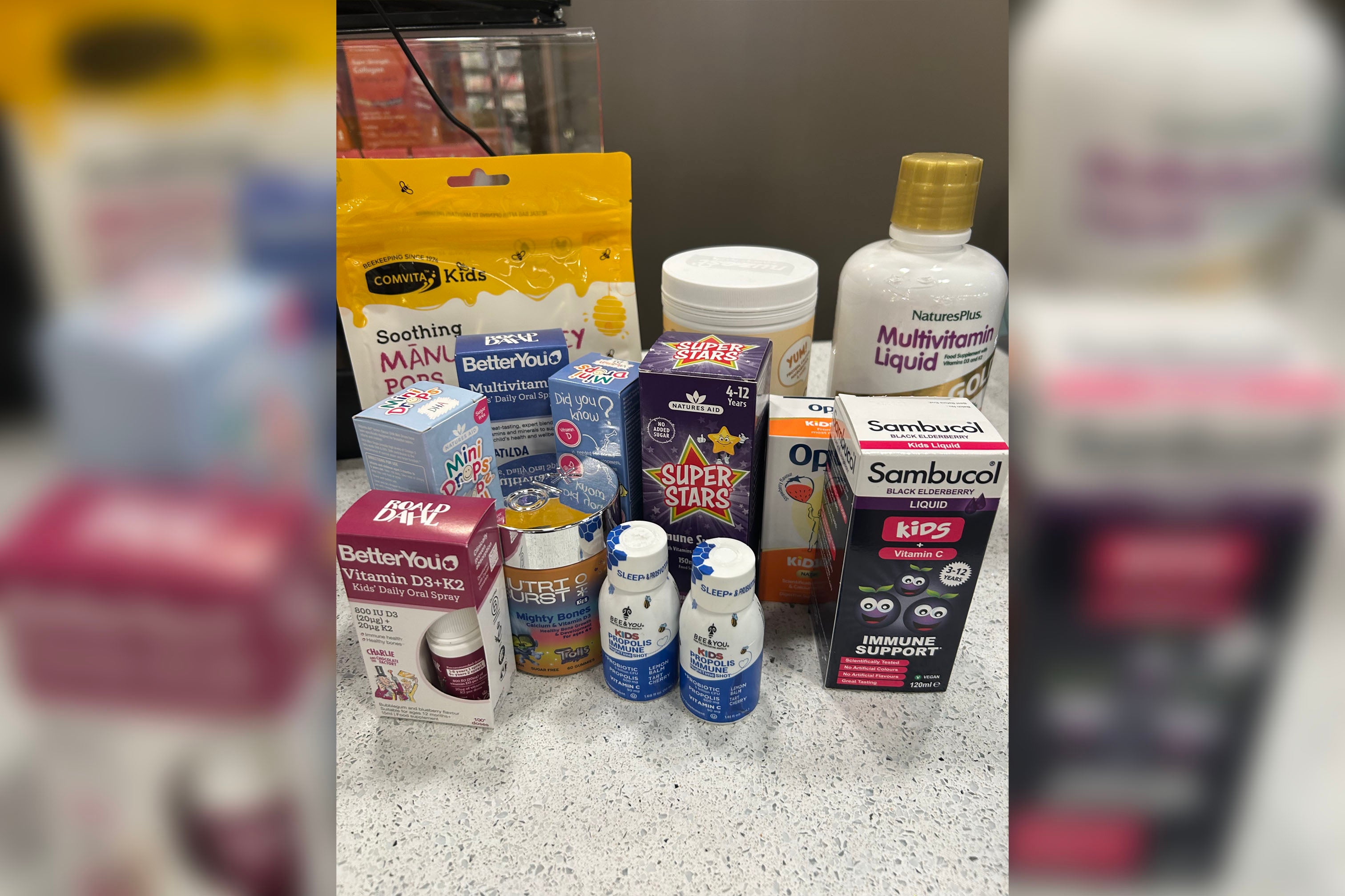

The last time I was at the till in Holland and Barrett, I spent £155 on vitamins and supplements in one swoop. That was before realising I had forgotten some items. With two fussy eaters at home, I’ve upgraded to the gold standard in children’s multivitamins, costing £28.49 for a jumbo bottle that they swig at breakfast.

According to the latest figures, UK parents spend on average £234 a year on vitamins and supplements for their children, mainly to boost immunity and focus. Only £234? I can spend that in a month. I am also buying magnesium supplements that support relaxation, sleep quality, and a balanced nervous system (£9.99), Vitamin D with K2 spray (£11.95) and children’s Omega 3 and DHA drops (£12.99). Then there are pricey probiotic supplements (£12.99) as well as calcium liquid, immune support and protein shakes.

I struggle to pay my energy bills as it is, and try to cut back on grocery shopping, but I never say no to buying these. It’s no wonder that 63 per cent of parents find these products increasingly expensive.

According to research from the buy-now, pay-later platform Clearpay, 92 per cent of parents purchased supplements for their child in the past year, with multivitamins, Vitamin C and Vitamin D being the most popular choices. There is a huge demand for certain supplements, with magnesium for children rising by 296 per cent year-on-year. Vitamin D sales also soared by 231 per cent,and probiotic drinks by 228 per cent. Parents are purchasing these items to help with boosting immunity (51 per cent), avoiding illness (36 per cent) and improving concentration (24 per cent) – and a whopping 44 per cent of parents intend to buy even more this year.

Yet despite the increase in spending, 44 per cent of parents struggle to work out if these supplements actually work. It doesn’t seem to matter. The appetite for them continues, with the global kids’ vitamins and supplements market valued at $6.3bn in 2024, and projected to reach more than $12bn by 2033, according to Market Intelo.

‘It’s not some fad. I am generally worried about my daughters’ nutrient-deficient diet – that fussy eating again – and how it might affect their gut health’ (Charlotte Cripps)

‘It’s not some fad. I am generally worried about my daughters’ nutrient-deficient diet – that fussy eating again – and how it might affect their gut health’ (Charlotte Cripps)

A major part of the wellness industry comes from celebrities pushing their own brands – or endorsing them, such as Gwyneth Paltrow, whose 19-second Instagram video in 2023 promoting a probiotics brand in her kitchen went viral. Kourtney Kardashian flogs her line of probiotics. Jennifer Lopez, Elle Macpherson, Venus Williams and Tom Brady have all dived into the world of supplements. It was only a matter of time before, like skincare, the trend filtered down to our kids.

But for me, it’s not some fad. I am generally worried about my daughters’ nutrient-deficient diet – that fussy eating again – and how it might affect their gut health. Poor gut health can affect everything from immunity and digestion to mood and cognitive function, and now scientists in the US and Germany have also discovered that a good gut microbiome can turn back the clock on cellular ageing and the onset of chronic disease.

Critics of Supplement Mums will claim that if a child eats a healthy, balanced diet, they don’t need anything more. That’s great, but how many parents have fussy eaters – mine included? More than half of UK pre-school children are picky with their food. At nine, my daughter, Lola, still won’t eat anything except fish fingers, pasta with tomato and pizza.

I have endlessly beaten myself over her diet. I once took her to see one of the world’s most sought-after food phobia gurus, who treats patients with avoidant or restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). He got her to try about 20 foods she’d never ordinarily dream of eating, but sadly, the effect was not long-lasting.

I’ve since learnt that fussy eating is caused by genes, not parenting. A 2024 study at the University of Leeds revealed that, on average, fussiness over food changed little from 16 months to 13 years old. About one in five children in the UK is iron-deficient, too. My kids are pescatarian – and only eat fish fingers. A vegan or plant-based diet may be lacking in certain nutrients. They also gag at the thought of bananas, sadly, because half of one is apparently equivalent to a dose of magnesium that many supplements provide.

Of course, I have to be careful not to double-dose, because some of the supplements contain extra vitamins that you may be getting from the multivitamin. That means I end up spending hours reading labels – and juggling liquids, gummies and drops.

I am looking at ways to cut my monthly vitamin bills, but choosing which supplement to ditch, other than the calcium liquid, is a real struggle. How do you choose to cut something from your child’s health?