GATA6 expression associates with immunoreactive stroma in human PDAC

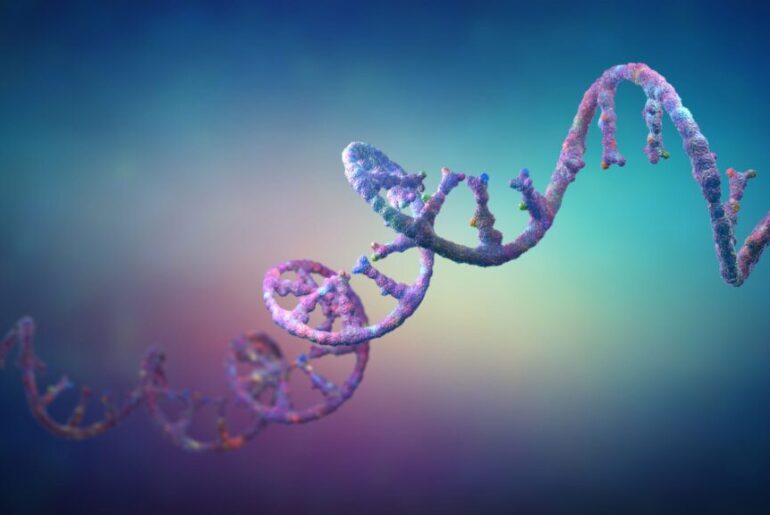

We assessed GATA6 expression specifically in tumor epithelial cells in a tissue microarray (TMA) from PDAC resections (n = 143) by IHC. Epithelial regions were manually annotated for each of the 594 cores by a trained pathologist before GATA6 expression was digitally quantified. All cores per patient were averaged, and patients were categorized into GATA6high, GATA6intermediate, or GATA6low groups by expression quantiles (Fig. S1a, Supplementary Dataset 1). The abundance of a panel of immune markers that was previously assessed in the cohort29 was then compared as a function of GATA6 expression in tumor cells. We found significantly higher levels of CD4+, CD20+, FOXP3+, CD68+, and tumor-infiltrating CD3+ and CD8+ cells in the high GATA6 expression group (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Dataset 1). Besides, a positive correlation was observed between tumor GATA6 and E-cadherin expression (Fig. S1a, Supplementary Dataset 1), supporting the specific expression of GATA6 in the classical PDAC subtype.

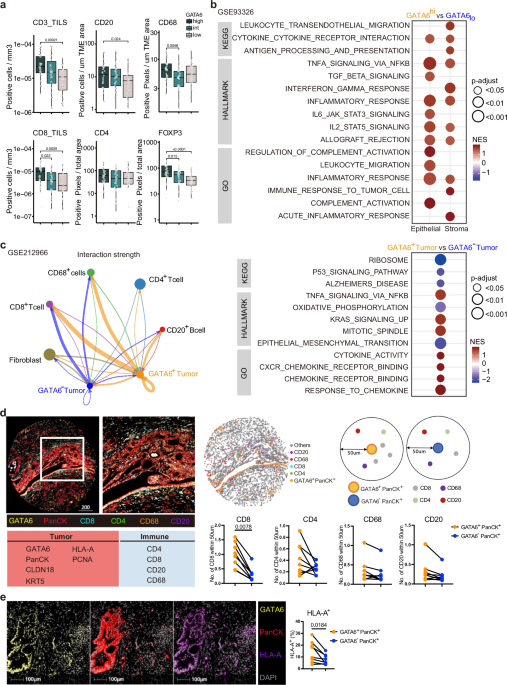

Fig. 1: GATA6 expression associates with immunoreactive stroma in human PDAC.

Phenotypic profiles of PDAC patients with differential GATA6 tumor expression at a protein and b transcriptomic levels. GATA6 expression in tumor epithelial cells in a TMA from PDAC resections (n = 143 biological replicates) was assessed by IHC. Epithelial regions were manually annotated for each of the 594 cores by a trained pathologist before GATA6 expression was digitally quantified. All cores per patient were averaged and patients categorized into GATA6high, GATA6intermediate, or GATA6low groups by expression quantiles. CD8, CD4, CD20, CD68, FOXP3 were stained by IHC in resections (n = 143 biological replicates) and quantified by QuPath bioimage analysis software. Expression levels of tumor-infiltrating (TILS) CD3 and CD8, CD20, CD68, CD4 and FOXP3 in each group are shown. Box plots show the median (center line), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds of box), and whiskers extending to the minima and maxima values. Individual data points represent independent patients. Statistical significance was calculated by Wilcoxon test. b Maurer et al. dataset (GSE93326, n = 65 biological replicates). Enrichment was tested against the differential expression profile of epithelium GATA6hi vs GATA6lo (n = 32 vs n = 32 biological replicates, cutoff: median) in epithelium and their paired stroma samples separately. c Cellular interaction analysis on GATA6+/− tumor cells in a single-cell RNA-sequencing dataset from Chen et al. (GSE212966, n = 6 biological replicates). Left panel: CellChat analysis of cellular interactions among GATA6+/− tumor cells and CD20+ B cells, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, CD68+ cells, and Fibroblasts. The line thickness represents the strength of the interaction signals, the direction of the arrows indicates the orientation of the signals. Right panel: GSEA was performed, and selected pathways enriched in GATA6+ tumor cells when compared to the GATA6− counterpart were shown. d Multiplex imaging by Phenocycler on human PDAC tissues (n = 8 biological replicates) demonstrated heterogeneous tumor GATA6 expression associated with infiltration of CD4+, CD8+, CD20+, and CD68+ cells in the neighborhood (left panel, bar unit: µm). Computational spatial analysis by HALO software showed higher number of immune cells in close proximity (<50 μM radical distance) of GATA6+ tumor cells than the GATA6− counterparts (n = 8 biological replicates) (right panel). Statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. e GATA6+ tumor cells (GATA6+PanCK+) express higher level of MHCI (HLA-A) than their negative counterpart (GATA6−PanCK+). Quantification was done by HALO software (n = 8 biological replicates). Bar unit: µm. Statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

To dissect the role of GATA6 in tumor cells and their associated stroma, we analyzed the RNA-sequencing dataset of Maurer et al.30 (GSE93326, n = 65), where PDAC malignant epithelium and stroma were procured by Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM). Patients were dichotomized into high (n = 32) and low (n = 32) tumor GATA6 expression groups (cutoff: median). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed and revealed strong immunological features in the high GATA6 epithelium group and their paired stroma (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Dataset 2). Notably, gene sets including inflammatory response, allograft rejection, TNFα via NFκB, IL2-STAT5, cytokine cytokine receptor interaction signaling are all commonly enriched in both GATA6high epithelium and the paired stroma. In addition, IL6-STAT3, leukocyte migration signaling are enriched in GATA6high epithelium, and leukocyte transendothelial migration, antigen processing and presentation, interferon gamma response, and immune response to tumor cell signaling are enriched in GATA6high stroma (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Dataset 2).

Next, we investigated the cellular interaction of GATA6+ tumor cells. We performed CellChat analysis with a public PDAC single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset (GSE212966, n = 6), to predict cellular interaction between GATA6+/− tumor cells and different cell types and found that GATA6+ tumor cells demonstrated stronger interaction specifically with CD8+ T cells, CD68+ macrophages and CD20+ B cells than GATA6− counterparts (Fig. 1c). GSEA from a comparison between GATA6+ and GATA6− tumor cells showed that GATA6+ tumor cells were enriched for genes involved in inflammatory response pathways including TNFα via NFκB, cytokine activity, chemokine receptor binding and response to chemokines (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Dataset 3), which was consistent with the GSEA results in GSE93326 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Dataset 2).

To validate the cellular interaction of GATA6+ tumor cells with immune cells at spatial level, we performed highly multiplex spatial imaging with Phenocycler on 8 therapy-naive human PDAC samples (Figs. 1d and S1b, c). Among these, 2 were resected PDAC primary tissues, while the remaining 6 cases were tissue microarray (TMA) cores of resected PDAC primary tumors (Fig. S1b, c, Supplementary Table 1). Four regions with heterogeneous GATA6 tumor expression were selected for imaging and analysis (Fig. S1b) from resected PDAC tissues, while whole tissue cores were included for analyses for TMA tissues (Fig. S1c). Average values of different ROIs or tissue cores were used for subsequent statistical analyses. 27 markers were included in the panel (Supplementary Dataset 6), and among which, 10 markers were analyzed for this study, focusing on the status of GATA6+ tumor cells and their interaction with immune cells (Fig. 1d). Proximity analysis was performed to measure the number of various immune populations in close proximity (<50 μM radical distance) of GATA6+ PanCK+ cells and GATA6− PanCK+ cells, respectively (Fig. 1d). The analyses revealed a significantly closer cellular interaction of GATA6+ PanCK+ cells with CD8+ cells, compared to GATA6− tumor cells. Similar trends can be observed for CD4+, CD68+, and CD20+ cells (Fig. 1d), although without statistical significance, given low sample numbers. Since antigen presentation-related gene sets were enriched in both tumor and stroma compartment of high GATA6 tumors (Fig. 1b), we examined and compared the expression of MHCI (HLA-A) in GATA6+ PanCK+ and GATA6− PanCK+ cells, and found that GATA6+ tumor cells express higher levels of MHCI than their negative counterpart (Fig. 1e), implying the higher antigenicity of GATA6+ tumor cells. To better elucidate the status of MHCI+ GATA6+ tumor cells, we examined the proportion of proliferative marker PCNA+ cells within the MHCI+ PanCK+ population, as well as in MHCI+ GATA6+ PanCK+ cells. We observed no significant difference, suggesting that MHCI and GATA6 expression levels may not be associated with the proliferation status of tumor cells (Fig. S1d).

GATA6 is associated with the classical PDAC subtype1,2,3,4,5. We examined its co-expression with claudin 18 (CLDN18), which was recently linked to the classical and immunogenic PDAC subtype5,31. Additionally, keratin 5 (KRT5), a basal-like subtype marker32, was included for subtype analysis (Fig. S1e). Analysis of eight PDAC samples revealed a high degree of tumor subtype heterogeneity based on these four markers. Notably, GATA6 and CLDN18 did not co-express with KRT5 in any of the cases, supporting their classification as classical subtype markers. As expected, KRT5 expression was restricted to a small proportion of tumor cells, leaving a substantial fraction of the tumor cell population unclassified. Moreover, not all CLDN18+ classical tumor cells expressed GATA6, and vice versa (Fig. S1e), highlighting intrinsic heterogeneity within the classical subtype. Interestingly, GATA6+ CLDN18− PanCK+ cells, but not GATA6- CLDN18+ PanCK+ cells, were in close proximity with CD8+ T cells (Fig. S1f), suggesting a potential immunogenic role of the GATA6+ tumor subpopulation within classical tumor cells. Therefore, we hypothesized that this GATA6+ tumor subpopulation might be a target population for tumor-immune interactions and therapeutic perturbation.

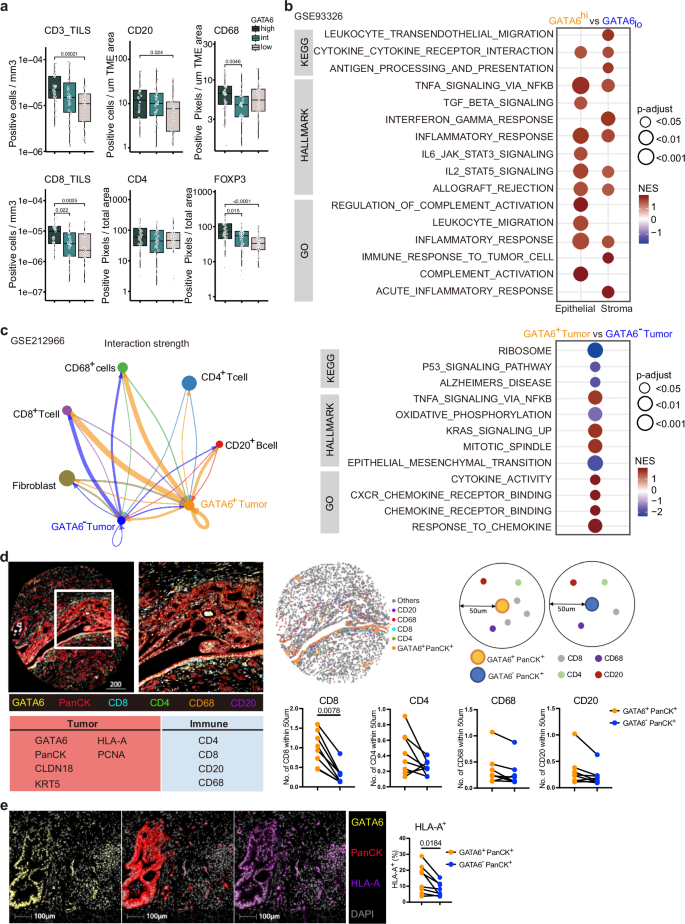

MEK inhibition induces GATA6+ tumor cell-specific MHCI upregulation

We next investigated the impact of targeted MEK inhibition on GATA6 tumor cell expression and the immunological responses of GATA6+ tumor cells. Six primary cell lines (511950, 60400, 70301, 60531, 511892, 60590) derived from spontaneous PDAC of six different Ptf1awt/Cre;Kraswt/LSL-G12D;Trp53loxP/loxP (CKP) mice and one primary cell line (110299) from spontaneous PDAC of Ptf1awt/Cre;Kraswt/LSL-G12D;Trp53loxPl/R172H (KPC) mouse33 were established. In addition, we included two Kraswt/LSL-G12D;Trp53 wt/LSL-R172H;Pdx1-Cre;Rosa26YFP/YFP(KPCY) derived cell lines 2838c3 and 6694C2, which were tumor cell clones generating tumors that recapitulated T cell-inflamed and non-T cell-inflamed TME in vivo, respectively34. We measured their GATA6 expression at protein level by flow cytometry (Fig. 2a) and dichotomized the cell lines into GATA6high (110299, 511950, 2838c3, 60400, 70301) and GATA6low (60531, 511892, 6694C2, 60590) groups (cutoff: median). We next generated corresponding long-term MEKi-treated counterparts from six of them (three GATA6high: 511950, 60400, 70301 vs three GATA6low: 60531, 511892, 60590) upon long-term trametinib treatment as previously described35 and compared their transcriptomic profiles (Fig. 2b). Notably, we observed enrichment of several immune-related gene sets, including allograft rejection, antigen processing and presentation, IFNα and IFNγ responses upon MEKi treatment only in GATA6high, but not in GATA6low cell lines (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Dataset 4).

Fig. 2: MEK inhibition induces GATA6-dependent MHCI upregulation.

a Nine primary murine PDAC cell lines were established from spontaneous murine PDAC models (CKP, KPC, and KPCY). Created with BioRender.com. Flow cytometry analysis was used to determine GATA6 protein expression in each line. Representative histograms show GATA6 staining (GATA6 antibody, GATA6 AB, red) versus isotype control (blue) in GATA6 high (GATA6hi) and low (GATA6lo) expressing cell lines. The cell lines were dichotomized into GATA6high (n = 5, orange) and GATA6low (n = 4, blue) groups. b The parental cells (Ctrl) of three GATA6high cell lines (60400, 511950, 70301) and three GATA6low cell lines (60590, 60531, 511892) were treated with increasing doses of MEKi (trametinib) until 100x of the cells’ initial IC50 to generate the corresponding long-term MEKi-treated cells (MEKi). Transcriptomic profiling by RNA sequencing of the parental (Ctrl) and long-term MEKi-treated (MEKi) cells was performed. GSEA of KEGG and HALLMARKs revealed gene sets that were significantly (P-adjust < 0.05) different between parental (Ctrl) and long-term MEKi-treated (MEKi) cells within GATA6high and GATA6low groups, respectively. c Surface MHCI (H-2Db) expression on control (Ctrl) and MEKi-treated (MEKi) cells of GATA6high (upper panel) and GATA6low group (lower panel) was assessed by flow cytometry (n = 4 biological replicates for cell line 60400, 511950, 511892, 60590, and 5 biological replicates for cell line 110299, 2838c3, 60531, 6694C2). MFI mean fluorescence intensity. Mean ± SD is shown. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. d Flow cytometric analysis of GATA6 expression in GATA6 knockout (KPCY1-CRISPR-GFP v2.1-gRNA-gCas9): gGATA6_KO-3 and gGATA6_KO-4, and negative control (gNT) cell lines (n = 4 biological replicates). Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. e Surface MHCI (H-2Db) expression on GATA6 knockout cell lines and negative control upon MEKi treatment (n = 4 biological replicates). MFI: mean fluorescence intensity. Mean ± SD is shown. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. f Schematic of the knock-in strategy for N-terminal AID-tagged gata6. Shown are components of the knock-in cassette, and the positions of primers for genomic PCR are marked by arrows. g Western blot showing GATA6 protein expression in 110299WT and 110299AID-GATA6 cells after 24 h treatment with 1 µM 5-Ph-IAA (n = 1 biological replicates). h Surface MHCI (H-2Db) expression on 110299WT and 110299AID-GATA6 cells treated with or without MEKi and/or 1 µM 5-Ph-IAA (n = 5 biological replicates). MFI: mean fluorescence intensity. Mean ± SD is shown. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test.

Impaired antigen presentation machinery and MHCI downregulation are frequently observed in PDAC and are considered as pivotal mechanisms for tumor immune evasion during the development of drug resistance. We assessed the surface MHCI expression upon MEKi treatment in four GATA6high and four GATA6low murine cell lines by flow cytometry. Intriguingly, significant induction of surface MHCI was observed upon MEKi treatment in GATA6high, but not in GATA6low cell lines (Fig. 2c). Notably, cell proliferation assays confirmed that there was no significant change in cell proliferation upon treatment (Fig. S2a), suggesting that the increase in MHCI in GATA6high cell lines was not associated with changes in cell proliferation.

Targeted GATA6 degradation ablated MEK inhibition-induced MHCI upregulation

To confirm the role of GATA6 in MEKi-induced MHCI expression, we generated two GATA6 knockout cell lines from the GATA6high cell line 2838c3 (Figs. 2d and S2b). Results show that MEKi-induced MHCI expression was completely abolished in GATA6 knockout cell lines (Fig. 2e), suggesting that MEKi upregulates surface MHCI expression of tumor cells in a GATA6-dependent manner.

Since cells may develop compensatory mechanisms in response to GATA6 loss, to specifically investigate the role of GATA6 in MEKi-induced MHCI expression in PDAC cells, we generated an auxin-inducible degron (AID) knock-in cell line for targeted GATA6 protein degradation (AID-GATA6) and corresponding wild-type (WT) (Figs. 2f and S2c–f). The murine primary PDAC cell line 11029933 was selected due to its high endogenous GATA6 expression (Fig. 2a). GATA6 degradation was observed after 8 h of incubation with 5-Ph-IAA, with more pronounced degradation after 24 h treatment (Figs. 2g and S2g). Both 110299WT and 110299AID-GATA6 cells were treated with 5-Ph-IAA for 24 h, followed by MEKi treatment for an additional 48 h. Upon MEKi treatment, significant MHCI upregulation was detected in 110299WT cells and 110299AID-GATA6 cells, which were not treated with 5-Ph-IAA, but not 110299AID-GATA6 cells treated with 5-Ph-IAA (Fig. 2h), further supporting the role of GATA6 in MEKi-induced MHCI regulation.

GATA6 is essential for MEKi-induced tumor control and anti-tumor cytotoxicity in vivo

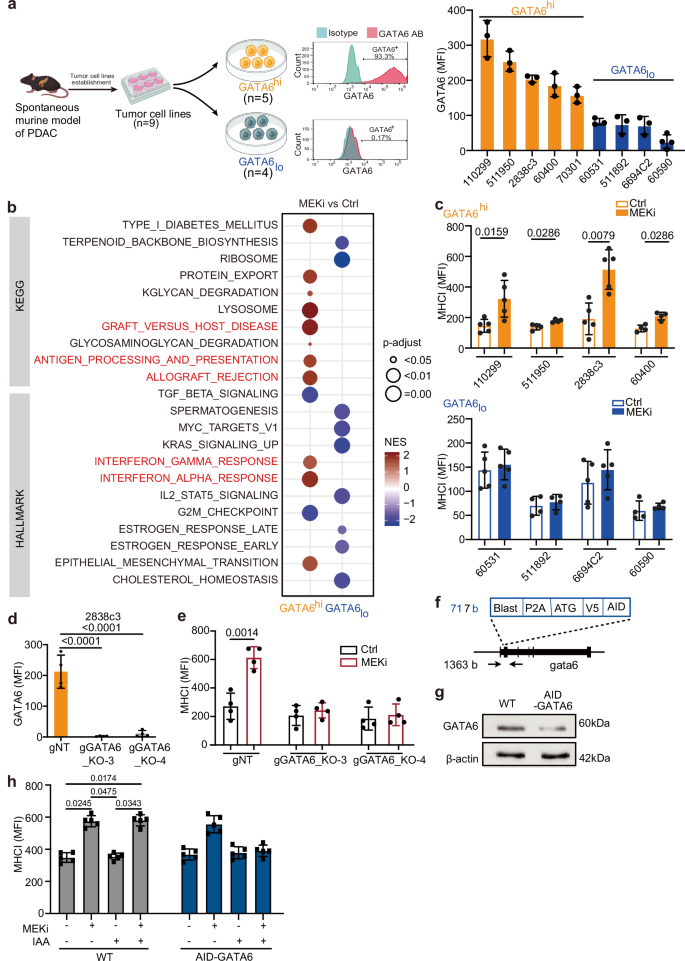

To investigate the role of GATA6 in MEKi-induced effects in vivo, we established syngeneic orthotopic tumor models using one GATA6high (110299) and one GATA6low (60590) cell line and treated them with MEKi (Fig. 3a). First, we examined GATA6 expression in the tumors and confirmed that the orthotopic tumors reflected the distinct GATA6 expression levels of the cell lines (Fig. 3b). Upon MEKi treatment, we observed no significant effect on the growth of GATA6low tumors (60590), while it significantly suppressed the growth of GATA6high tumors (110299) (Figs. 3c and S3a, b).

Fig. 3: GATA6 is essential for MEKi-induced tumor control and anti-tumor cytotoxicity in vivo.

a Schematic diagram showing the experimental workflow. Orthotopic tumors derived from GATA6low (60590) or GATA6high (110299) cell lines were monitored weekly by 3D ultrasound imaging. MEKi treatment was initiated when tumor volume (TV) reached 200–400 mm³, and experiments were terminated when tumor volume (TV) reached approximately 1000 mm³. Created with BioRender.com. b IHC staining of GATA6 in 60590 and 110299 tumors without treatment. The percentage of GATA6⁺ cells out of total cells was quantified by HALO software (n = 5 independent mice per group). Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Individual data points represent independent mice. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. c Tumor volume (TV) dynamics following MEKi treatment. Left panel: representative 3D ultrasound images of 110299 tumors at post 1 week with or without MEKi (Ctrl: vehicle control) treatment. Right panel: Changes in tumor volume from pre- to post 1 week treatment with or without MEKi in both models (n = 4 independent mice for the 60590 model, and n = 5 independent mice for the 110299 model). Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Individual data points represent independent mice. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test. d IHC staining of MHCI, CD8, GzmB, cleaved caspase-3 (Cl casp3), and phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1) in 110299 tumors with or without MEKi treatment. The proportion of marker-positive cells out of total cells quantified by HALO software is shown below (n = 4 independent mice for the 60590 model, and n = 5 independent mice for the 110299 model). Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Individual data points represent independent mice. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. e Schematic diagram of the in vivo MEKi treatment in targeted GATA6 degradation model. Created with BioRender.com. Orthotopic tumors were established using 110299AID-GATA6 cells or 110299WT cells. GATA6 degradation was induced by daily administration of 5-Ph-IAA (auxin) after tumor formation. MEKi treatment was started 3 days after auxin administration. f Tumor growth curves showing the ablation of MEKi-induced tumor inhibition of 110299 orthotopic tumors upon GATA6 degradation (n = 5 independent mice for each group). g IHC staining confirmed GATA6 degradation after auxin treatment in 110299AID-GATA6 tumors. Right panel: Quantification of GATA6⁺ cells out of total cells by HALO software (n = 5 independent mice for each group). Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Individual data points represent independent mice. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. h IHC analysis in GATA6-depleted tumors showing abolished MEKi-induced increases in MHCI, CD8, Cl casp3, and pSTAT1. Right panel: Quantification of marker-positive cells out of total cells by HALO software (n = 5 independent mice for each group). Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Individual data points represent independent mice. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. Scale bar: μm.

Histological analyses of GATA6high tumors revealed elevated MHCI expression following MEKi treatment (Fig. 3d). Additionally, we observed increased infiltration of CD8+ and granzyme B (GzmB)+ cells, with cytotoxicity reflected by higher levels of cleaved caspase-3 (Cl casp3) in MEKi-treated tumors (Fig. 3d). Our previous analysis showed that MEKi-treated GATA6high tumor cells were enriched for IFNγ response signature (Fig. 2b). Since IFNγ is a key regulator for MHCI expression on tumor cells, we deduced that GATA6 degradation might disrupt IFNγ response that led to ablated MHCI expression on the tumor cells. Therefore, we assessed pSTAT1, a key downstream signaling molecule of IFNγ pathway responsible for regulating MHCI expression36. The results showed strong pSTAT1 expression in GATA6high tumors, with even more intense pSTAT1 signals in MEKi-treated tumors (Fig. 3d). In contrast, GATA6low tumors, which showed relatively low expression of pSTAT1, exhibited minimal or no expression of MHCI, CD8, or Cl casp3 upon MEKi treatment (Fig. S3c).

To confirm the role of GATA6 in MEKi-induced anti-tumor responses in the 110299 model, 110299AID-GATA6 cells and 110299WT control cells were transplanted, and 5-Ph-IAA (auxin) was administered to degrade GATA6 protein only after tumor formation (200–400 mm³) to ensure that GATA6 degradation did not interfere with tumor development or the immune microenvironment before MEKi treatment (Fig. 3e). GATA6 levels were assessed at different time points after 5-Ph-IAA treatment, and GATA6 expression was notably suppressed by more than 50% after 2 days of treatment (Fig. S3d). MEKi treatment was initiated 3 days after GATA6 degradation (Fig. 3e), and strikingly, the MEKi-induced tumor suppression was completely abolished upon GATA6 degradation (Fig. 3f). Tumors were examined histologically, and significant GATA6 degradation in the tumors was confirmed (Fig. 3g). Notably, MEKi-induced increases in MHCI, CD8, Cl casp3, and pSTAT1 were entirely abolished in the GATA6-degraded model of 110299AID-GATA6 tumors (Fig. 3h), indicating that GATA6 largely contributes to the MEKi-induced anti-tumor responses. It is noteworthy that 110299WT tumors treated with 5-Ph-IAA showed no difference in tumor growth (Fig. S3e).

In addition to CD8+ cells, CD4+ cell infiltration was also enhanced in 110299AID-GATA6 tumors following MEKi treatment, although MHCII levels remained unchanged (Fig. S3f). Strikingly, MEKi-induced CD4+ cell infiltration persisted despite GATA6 degradation (Fig. S3f), indicating that the GATA6-dependent MEKi-induced tumor inhibition is not mediated by CD4+ cells. These findings highlight a specific role for GATA6 in mediating MEKi-induced anti-tumor cytotoxic responses via the IFNγ-MHCI axis.

MEKi promotes tumor MHCI expression in GATA6+ PDAC subtype with cell state transition in patient-derived xenografts

While MEKi promotes MHCI upregulation, our previous findings revealed an enrichment of EMT-associated features in long-term MEKi-treated cells derived from CKP tumors35, irrespective of subtype, as indicated by transcriptomic profiling. Given that GATA6 is a known suppressor of EMT in PDAC cells, MEKi may drive tumor cell state transitions by downregulating GATA6 expression. Consistently, analysis of orthotopic tumors in the GATA6high 110299 model also confirmed a reduction in GATA6 expression following MEKi treatment (Fig. S4a).

To confirm the reduction of epithelial features following MEKi treatment in a spontaneous mouse model that closely recapitulates PDAC tumor heterogeneity, CKP mice, which develop aggressive endogenous PDAC at 4–6 weeks of age, were treated with MEKi until the study endpoint (Fig. S4b). MEKi-treated tumors exhibited pronounced shrinkage during the first 2 weeks of treatment compared to vehicle controls (Fig. S4c). However, rapid tumor recurrence was observed in all MEKi-treated mice approximately 3 weeks after treatment (Fig. S4c). Notably, E-cadherin expression was significantly reduced in recurrent tumors following MEKi treatment (Fig. S4d), indicating a loss of epithelial lineage features.

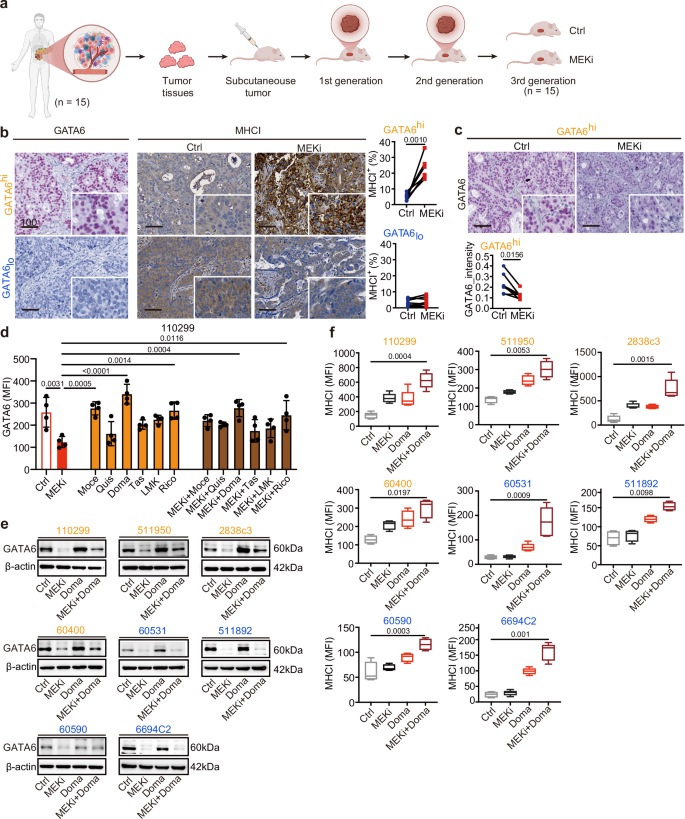

To validate these findings in a clinically relevant setting, we analyzed GATA6 and MHCI expression levels in 15 distinct patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) from the CAM-PaC (Integrative Analysis of Gene Functions in Cellular and Animal Models of Pancreatic Cancer) cohort37 (Fig. 4a). Based on baseline GATA6 expression in tumors without MEKi treatment, the 15 PDXs were stratified into GATA6high (n = 7) and GATA6low (n = 8) groups (Fig. S5a). MEKi treatment significantly upregulated MHCI expression in GATA6high tumors but not in GATA6low tumors (Fig. 4b), consistent with our previous in vitro findings. Notably, MEKi-treated GATA6high tumors exhibited a reduction in GATA6 expression (Fig. 4c) alongside an increase in the mesenchymal marker KRT81 (Fig. S5b), suggesting a tumor cell state transition. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in GATA6low tumors (Fig. S5c).

Fig. 4: MEKi reduces GATA6 expression that is restored by HDAC inhibitors with augmented MHCI expression.

a Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) from 15 PDAC patients were transplanted subcutaneously into athymic nude mice, and the mice of third generation were used for MEKi treatment. When tumor volume reached 200 mm3, the mice were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl) or MEKi. Tumors were harvested after 4 weeks of treatment. Created with BioRender.com. b IHC staining of GATA6 and MHCI of the xenograft tumors was performed, and the proportion of marker-positive cells out of total cells was quantified by Definiens software. Xenografts were dichotomized into GATA6high (GATA6hi, n = 7 independent mice) and GATAlow (GATAlo, n = 8 independent mice) expression groups using median GATA6+ cells (% total) as cutoff. MHCI+ cells (% total) were quantified by Definiens and compared between vehicle control and corresponding MEKi-treated mice in GATA6high and GATAlow expression groups, respectively. Statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. c IHC staining showing reduction of GATA6 expression in MEKi-treated tumors in GATA6high expression group. Signal intensities were quantified by Definiens and compared between vehicle control and MEKi-treated mice groups (n = 7 independent mice for each group). Statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. d Flow cytometry analysis of GATA6 expression in 110299 cells treated with MEKi, class I HDAC inhibitors (mocetinostat, quisinostat, domatinostat), class II HDAC inhibitors (tasquinimod, LMK235, ricolinostat), or their combinations (n = 4 independent experiments for each cell line). Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Individual dots represent independent biological replicates. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test. e Western blot analysis of GATA6 protein levels in four GATA6high (orange: 110299, 511950, 2838c3, 60400) and four GATA6low (blue: 60531, 511892, 60590, 6694c2) murine PDAC cell lines following treatment with MEKi and/or domatinostat; β-actin served as a loading control (n = 1 independent experiment). f Surface MHCI (H-2Db) expression in the four GATA6high (orange) and four GATA6low (blue) murine PDAC cell lines treated with MEKi and/or domatinostat, assessed by flow cytometry (n = 4 independent experiments for cell line 511950, 60400, 511892, 60590, and 5 independent experiments for cell line 110299, 2838c3, 60531, 6694C2). Data are presented as box plots: the center line indicates the median, the bounds of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to minima and maxima. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test were used. Ctrl: vehicle control; MEKi: trametinib; Moce: mocetinostat; Quis: quisinostat; Doma: domatinostat; Tas: tasquinimod; LMK: LMK235; Rico: ricolinostat. MFI mean fluorescence intensity. Scale bar: μm.

Collectively, these findings suggest that while MEKi enhances MHCI expression in GATA6high tumor cells, it concurrently promotes a cell state transition by suppressing GATA6 expression not only in murine but also in human PDAC cells.

HDAC inhibitors restored GATA6 expression and promoted MHCI expression

Given the critical role of GATA6 in MEKi-induced anti-tumor immune responses, mitigating MEKi-induced EMT while preserving an immune-amendable GATA6+ tumor cell population is of therapeutic interest. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) have been reported to inhibit EMT and enhance anti-tumor cytotoxicity by promoting antigen presentation25,28,38. Thus, we selected a PDX with high GATA6 expression to assess the combination of the MEKi trametinib with the class I HDACi mocetinostat. While MEKi treatment slightly reduced GATA6 levels, the combination with mocetinostat significantly restored GATA6 expression in tumors (Fig. S5d, upper panel). Notably, while MEKi alone increased MHCI expression, this effect was further enhanced upon combination treatment (Fig. S5d, lower panel).

Given the differential therapeutic and toxicity profiles of various HDACi, we next evaluated a panel of class I (mocetinostat, quisinostat, domatinostat) and class II (tasquinimod, LMK235, ricolinostat) HDAC inhibitors, either alone or in combination with MEKi, for their effects on GATA6 expression in the GATA6high murine PDAC cell line 110299. MEKi treatment significantly reduced GATA6 expression, while the addition of domatinostat largely restored its levels (Fig. 4d). This aligns with previous findings that domatinostat promotes epithelial gene expression in PDAC cells through a BRD4- and MYC-dependent mechanism25. These findings were further confirmed by western blot analysis across eight murine PDAC cell lines, where GATA6 restoration was observed in all GATA6high cell lines upon combination treatment with MEKi and domatinostat, but not obvious in GATA6low cell lines (Fig. 4e). We also examined the epithelial marker E-cadherin and the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin. While MEKi consistently induced EMT across all cell lines, its combination with domatinostat effectively reversed this effect in GATA6high cell lines by restoring E-cadherin and suppressing N-cadherin expression (Fig. S5e). These findings suggest that HDAC inhibition restores GATA6 expression by counteracting MEKi-induced cell state transitions.

In addition to EMT inhibition, previous studies have shown that HDACi promotes anti-tumor cytotoxicity by enhancing antigen presentation. To further investigate this, we assessed the effects of class I (mocetinostat, quisinostat, domatinostat) and class II (tasquinimod, LMK235, ricolinostat) HDACi, alone or in combination with MEKi, on MHCI expression in GATA6high and GATA6low murine PDAC cell lines. All HDACi treatments increased surface MHCI expression, with class I HDACi generally inducing a greater effect than class II HDACi (Figs. 4f and S5f, g). Notably, while MEKi-induced MHCI upregulation was restricted to GATA6high cell lines, HDACi treatment increased MHCI expression also in GATA6low cell lines (Figs. 4f and S5f, g). Furthermore, combination treatment with MEKi further augmented surface MHCI levels across most of the cell lines, with the most pronounced increase observed for the MEKi and domatinostat combination (Figs. 4f and S5f, g).

These findings suggest that HDACi not only counteract MEKi-induced GATA6 suppression, but also enhance MHCI expression on tumor cells, thereby potentially augmenting anti-tumor immunity.

Combination of MEKi and HDACi promotes tumor-specific T cell anti-tumor cytotoxicity specifically in GATA6high tumor cells in vitro

Next, we investigated whether the MEKi- and HDACi-induced upregulation of MHCI expression translates into enhanced anti-tumor cytotoxicity. Given the typically low mutational burden of PDAC, which limits the availability of neoantigens, we utilized a next-generation dual recombination (Cre/Lox; Flp/FRT) mouse model, FKPC2GP, which enables temporally and spatially controlled expression of the model tumor antigen LCMV-gp33 (Fig. 5a)39,40,41.

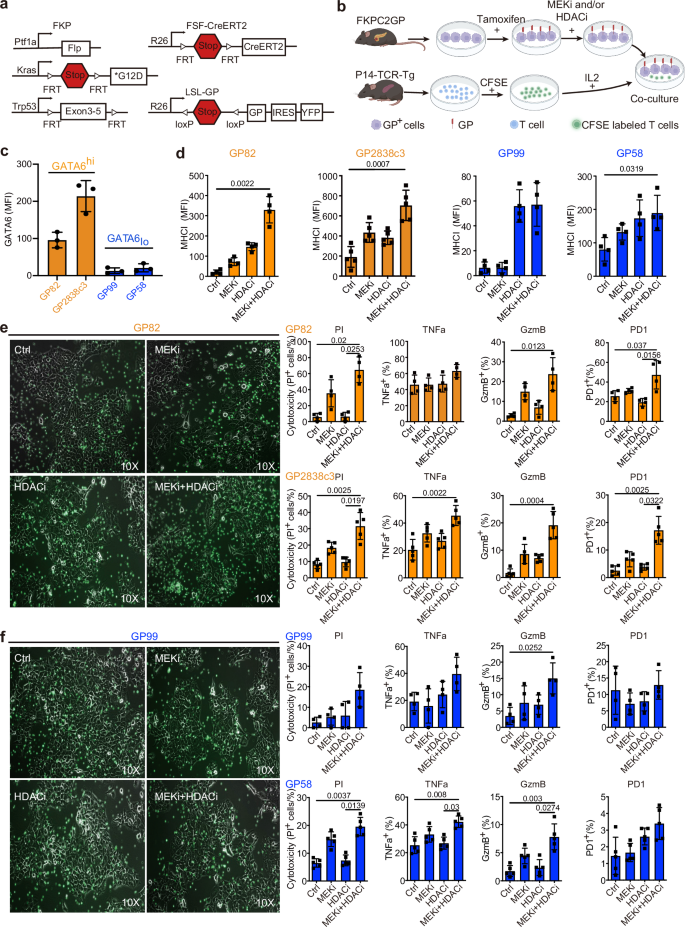

Fig. 5: MEKi treatment promotes tumor-specific T cell anti-tumor cytotoxicity in vitro.

a Genetic strategy to induce spatially and temporally controlled GP33 expression by tamoxifen-mediated activation of CreERT2 in pancreatic cells harboring mutant KrasG12D and loss of Tp53. Ptf1awt/flp;Kraswt/FSF-G12D;Trp53tm1.1Dgk (FKP) mice crossed to Gt(ROSA)26Sortm3(CAG-Cre/ERT2)Dsa(R26FSF-CAG−CreERT2) and Gt(ROSA)26SortmloxP-STOP-loxP-GP-IRES-YFP(R26LSL-GP) strains to generate FKPC2GP mice. b Experimental setup for co-culture of treated GP, LCMV-gp33-expressing cell lines derived from FKPC2GP tumor, and the gp33 reactive T cells isolated from the spleen of P14-TCR-Tg mice. The treatment follows the experiments of CKP cell lines. Created with BioRender.com. c Flow cytometric analysis of GATA6 expression in four GP cell lines (GP82, GP2838c3, GP99, GP58, n = 3 independent experiments). GP82 and GP2838c3 are defined as GATA6high, and GP99 and GP59 are defined as GATA6low. d Surface MHCI (H-2Db) expression on GP mouse cell lines 72 h treatment as assessed by flow cytometry (n = 4 independent experiments for cell line GP82, GP99, GP58, and 5 independent experiments for cell line GP2838c3). MFI: mean fluorescence intensity. Mean ± SD is shown. One-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test were used. Treated GATA6high (e) and GATA6low (f) GP cells were co-cultured with LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells (CFSE-labeled, green) for 2 days. Left panel: Microscopic images of treated GP cells and LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells (CFSE-labeled, green) after 2 days of co-culture. Right panel: Cytotoxicity level (PI+ %) of GP cells upon co-culture with LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells assessed by flow cytometry. Percentage of CD8+ cells that are positive for cytotoxic markers TNFa, GzmB, and activation PD1 (% in total T cells) assessed by flow cytometry (n = 4 independent experiments performed with LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells isolated from 4 different mice for cell line GP82, GP99, and n = 5 independent experiments performed with LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells isolated from 5 different mice for cell line GP2838c3 and GP58). MFI: mean fluorescence intensity. Mean ± SD is shown. One-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test were used. Ctrl: vehicle control; MEKi: trametinib; HDACi: domatinostat.

To assess tumor-specific cytotoxicity, we established four low-passage FKPC2GP-derived primary cell lines: GP58, GP82, and GP99, which express LCMV-gp33 upon tamoxifen induction in vitro, and GP2838c3, which constitutively expresses LCMV-gp33. Following treatment with MEKi and HDACi, LCMV-gp33+ tumor cells were co-cultured with LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells isolated from the spleens of P14-TCR-Tg mice (Fig. 5b).

Baseline GATA6 expression levels were evaluated across these cell lines, revealing that GP82 and GP2838c3 exhibited higher GATA6 expression compared to GP99 and GP58 (Fig. 5c). Based on these findings, we classified GP82 and GP2838c3 as GATA6high models and GP99 and GP58 as GATA6low models for subsequent analyses.

Consistent with our earlier observations, GATA6high GP82 and GP2838c3 cells exhibited a significant increase in surface MHCI expression following combined MEKi and HDACi treatment (Fig. 5d). MHCI expression was also upregulated by HDACi and combined MEKi and HDACi treatment on GATA6low GP99 and GP58 cells, although the magnitude of increase was smaller (Fig. 5d).

To evaluate the functional impact of these changes on anti-tumor immunity, all four LCMV-gp33-expressing tumor cells were co-cultured with LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells isolated from the spleens of P14-TCR-Tg mice. Combined MEKi and HDACi treatment led to a marked accumulation of LCMV-gp33-specific T cells, accompanied by prominent tumor cell death in GATA6high co-cultures (Fig. 5e). Propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometric analysis confirmed that cytotoxicity was significantly elevated in LCMV-gp33-induced GATA6high cells upon treatment (Fig. 5e).

In addition, we assessed the activation status of LCMV-gp33-reactive T cells within the co-culture system. Notably, GzmB and PD1 expression was significantly increased in T cells co-cultured with GATA6high tumor cells treated with MEKi and HDACi, further supporting enhanced T cell activation and tumor-specific cytotoxicity (Fig. 5e). Notably, similar trends could also be observed in GATA6low co-cultures, although the cytotoxic effects were less prominent than in the GATA6high co-cultures (Fig. 5f). Together, these findings demonstrate that combined MEKi and HDACi treatment induces MHCI upregulation in PDAC cells, which translates into enhanced tumor-specific T cell cytotoxicity.

MEKi and HDACi combination treatment enhances CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor suppression in orthotopic mouse model

To validate the anti-tumor cytotoxic effects of combined MEKi and HDACi treatment, we administered the combination therapy in an orthotopic mouse model derived from the GATA6high cell line 110299 (Fig. S6a). Besides, in order to investigate the involvement of CD8+ T cells in the anti-tumor response elicited by the combination therapy, we pre-treated mice with a CD8-depleting antibody prior to administering the combination regimen (Fig. S6b).

Upon combined MEKi and HDACi treatment, tumor growth was markedly suppressed (Fig. S6c). Despite a slight reduction of GATA6 when compared to control tumors, the high proportion of GATA6+ tumor cells remained responsive to the MEKi and HDACi combination therapy, exhibiting significant upregulation of MHCI, increased CD8+ T cell infiltration, and elevated cl casp3 expression (Fig. S6d). These findings suggest that the MEKi and HDACi combined treatment preserves the GATA6-expressing tumor population, which responds by enhancing MHCI expression, ultimately leading to increased CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Notably, the tumor-suppressive effect of the MEKi and HDACi combined treatment was fully abrogated in CD8-depleted mice (Fig. S6c). Histological analysis confirmed effective CD8+ T cell depletion following anti-CD8 antibody treatment (Fig. S6d). Importantly, tumor cell GATA6 expression remained largely unchanged, while MHCI expression stayed elevated following MEKi and HDACi combination therapy, regardless of CD8 status, suggesting that MHCI upregulation is independent of CD8+ T cell activity (Fig. S6d). In contrast, increase of Cl casp3 after MEKi and HDACi combination therapy was abolished when CD8+ T cells were depleted, further supporting the critical role of CD8+ T cells in mediating the anti-tumor effects of the combined MEK and HDAC inhibition.

Combination of MEKi and HDACi prolongs survival of CKP mice with restored GATA6 and MHCI expression

We next assessed the efficacy of a combined MEK and HDAC inhibition strategy in a highly aggressive, endogenous PDAC mouse model to reflect better the immunosuppressive, desmoplastic, and heterogenic features of human disease and evaluate its potential clinical relevance. CKP mice, aged 6 weeks and presenting measurable advanced tumors, were treated with or without MEKi and/or HDACi until the experimental endpoint (Fig. 6a). While both monotherapies significantly extended survival compared to vehicle-treated controls, the combination treatment further enhanced survival relative to either monotherapy (Fig. 6b).

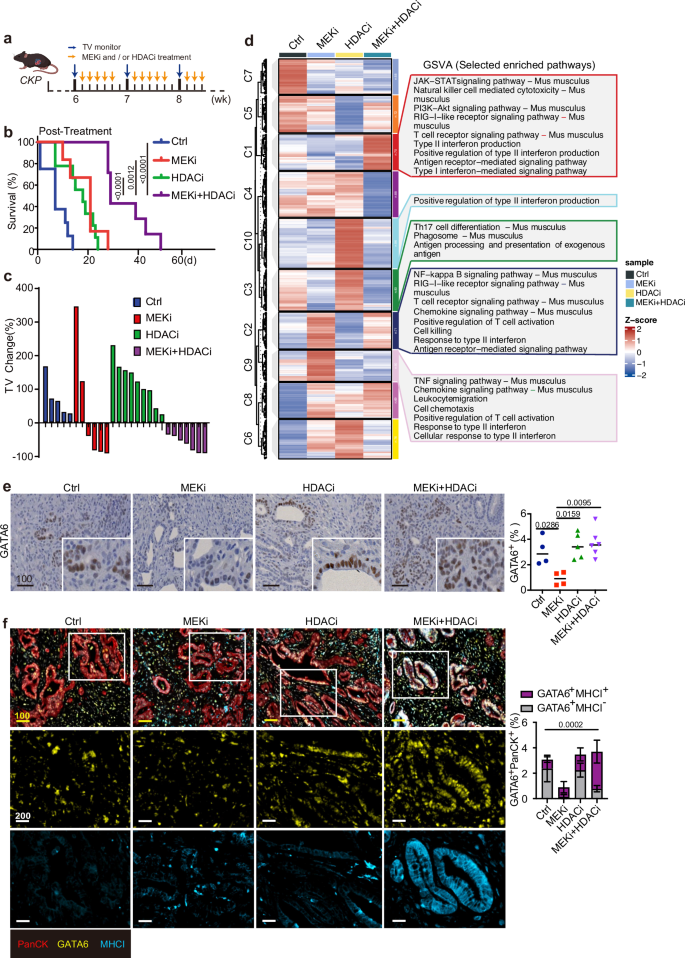

Fig. 6: Combined MEK and HDAC inhibition prolongs survival of CKP mice with restored GATA6 and MHCI expression.

a Timeline for treatment of CKP mice with vehicle control, MEKi, and/or HDACi. Orange arrows indicate the treatment schedule. Blue arrows indicate the schedule of tumor volume (TV) monitoring by 3D ultrasound imaging. Created with BioRender.com. b Kaplan-Meier plot shows post-treatment survival analysis from the data of CKP mice. Ctrl: n = 8 independent mice, median = 7 days; MEKi: n = 6 independent mice, median = 21 days; HDACi: n = 9 independent mice, median = 18 days; MEKi+HDACi: n = 7 independent mice, median = 29 days. Statistical significance of survival differences was determined by the two-sided log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. c Waterfall plot of the tumor volume (TV) percentage change for individual CKP mouse in different treatments (n = 5 independent mice for Ctrl group, n = 7 independent mice for MEKi group, n = 6 independent mice for HDACi group, n = 5 independent mice for MEKi+HDACi group). d Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) of the immune-related transcriptomic profiles of CKP tumors treated with or without MEKi and/or HDACi using the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling. Left: heatmap showing differential expression of immune-related genes in the 4 treatment groups. Selected statistically significant pathways (p < 0.05) enriched in different groups are shown in the right panel. Z-scores represent relative enrichment levels across samples (red: upregulated, blue: downregulated). e IHC staining of GATA6 in CKP tumors with or without MEKi and/or HDACi treatment. The right panels show the percentage of respective positive cells out of total cells in the whole tumorous tissues as quantified by Definiens software (n = 4 independent mice for Ctrl group, n = 4 independent mice for MEKi group, n = 5 independent mice for HDACi group, n = 6 independent mice for MEKi+HDACi group). Mean ± SD is shown. One-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test were used. f mIF staining of GATA6, MHCI, and PanCK was performed in CKP tumors. Left panel: representative images showing co-expression of MHCI and GATA6 in PanCK+ tumor cells from 4 treatment groups. Right panel: The percentage of GATA6+MHCI+PanCK+ and GATA6+MHCI−PanCK+ cells out of total cells was quantified by HALO software (n = 4 independent mice for Ctrl group, n = 4 independent mice for MEKi group, n = 5 independent mice for HDACi group, n = 6 independent mice for MEKi+HDACi group). Mean ± SD is shown. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test were used. Ctrl: vehicle control; MEKi: trametinib; HDACi: domatinostat; MEKi + HDACi: trametinib + domatinostat. Scale bar: µm.

Tumor volumes assessed by 3D ultrasound imaging showed only 4 out of 6 mice treated with MEKi and none of HDACi-treated mice exhibited tumor shrinkage (Fig. 6c). In contrast, all mice treated with the combination regimen (n = 7) showed a sustained reduction in tumor volume throughout the treatment period (Fig. 6c). Importantly, tumor control was maintained in all combination-treated mice at the experimental endpoint, and these animals were euthanized due to weight loss rather than tumor progression (Fig. S7a). Tumor volume changes could not be evaluated in 3 control mice due to their short survival time (less than 1 week after study entry) (Fig. 6c).

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the survival benefit of combination therapy, we compared the immune-related transcriptomic profiles of CKP tumors treated with or without MEKi and/or HDACi using the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) revealed that MEKi alone induced the expression of several immune-related gene sets, including antigen receptor-mediated signaling, T cell receptor signaling, type II interferon activation, T cell activation, and cytotoxicity (Fig. 6d), suggesting its role in promoting T cell-mediated immunity. HDACi alone had a more subtle effect on the tumor immune microenvironment, inducing pathways only related to antigen processing and type II interferon regulation (Fig. 6d). Notably, combined MEKi and HDACi treatment activated a broader range of immune pathways, including those enriched in both monotherapies (Fig. 6d).

To further elucidate the differential effects of MEKi alone versus combination treatment, we compared the immune-related transcriptomic profiles and found that the combination therapy significantly upregulated genes associated with T cell function and antigen presentation (Fig. S7b,c). Additionally, the combination group exhibited higher scores in pathways related to antigenicity, such as MHC and antigen processing (Fig. S7b, c), suggesting that combined MEKi and HDACi enhances tumor antigenicity compared to MEKi alone.

We next assessed GATA6 expression in CKP tumors. Notably, GATA6 expression, which was suppressed in MEKi-treated tumors, was restored following combination treatment with domatinostat (Fig. 6e), suggesting that HDACi mitigated the MEKi-induced loss of classical-type tumor cells.

We then performed multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) staining for GATA6 and MHCI in CKP tumors. Strong co-expression of these two molecules was observed, particularly in the combination treatment group (Fig. 6f). Quantitative analysis revealed that, upon MEKi treatment alone, the majority of GATA6+ tumor cells were also MHCI+, though GATA6 expression was significantly reduced. Importantly, combination treatment with HDACi significantly restored GATA6+ tumors, with the majority remaining MHCI+ (Fig. 6f, right panel). These findings suggest that HDACi suppresses the MEKi-induced transition and preserves the GATA6+ classical cell state of tumor cells, which are responsive to MEKi with proficient MHCI upregulation. This mechanism enhances the overall antigenicity of the tumors, thereby promoting anti-tumor immune responses.

Enhanced tumor MHCI expression induced by combined MEK and HDAC inhibition is associated with increased cytotoxic T-cell infiltration and tumor apoptosis in vivo

We next examined the effect of treatment on T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity. IHC analysis revealed a significant increase in infiltrating CD8+ T cells in tumors treated with the combination regimen compared to the other groups (Fig. 7a). Notably, the T cell activation marker PD1 and the cytotoxic marker GzmB were both significantly elevated in combination-treated tumors (Fig. 7a). The enhanced anti-tumor cytotoxicity observed with combination treatment was further supported by increased Cl casp3 levels, with no significant changes seen in the single treatment (Fig. 7b).

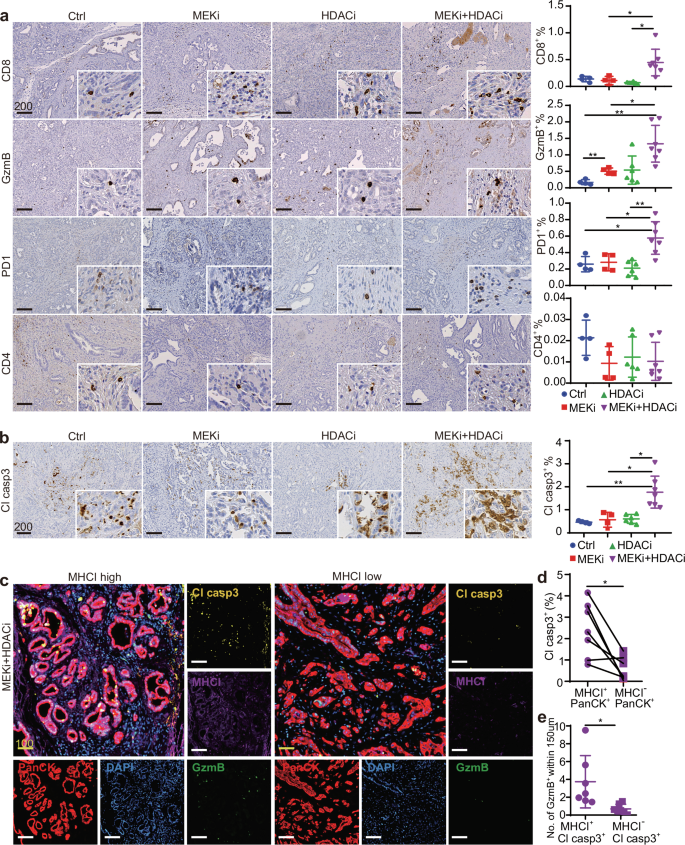

Fig. 7: Combined MEKi and HDACi treatment enhances cytotoxic T cell infiltration and tumor apoptosis in vivo.

IHC staining of a T cell marker CD8 and CD4, activated T cell marker PD1, cytotoxic T cell marker GzmB, and b apoptosis marker Cl casp3 in CKP tumors with designed treatments. The right panels show the percentage of respective positive cells out of the total cells in the whole tumorous tissues as quantified by Definiens software (n = 4 independent mice for Ctrl group, n = 4 independent mice for MEKi group, n = 6 independent mice for HDACi group, n = 7 independent mice for MEKi+HDACi group). Mean ± SD is shown. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test were used. c mIF staining of combinatory MEKi and HDACi-treated CKP mice showing increased GzmB+ and Cl casp3+ cells in high tumor MHCI+ expression areas (n = 7). d Co-expression analysis shows the percentage of Cl casp3+ tumor cells within MHCI+PanCK+ and MHCI−PanCK+ population (n = 7). The percentage of respective positive cells out of the total cells was quantified by HALO software. Statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. e Computational spatial analysis shows higher number of GzmB+ cells in close proximity (<150 μM radical distance) of MHCI+ Cl casp3+ cells when compared to MHCI− Cl casp3+ cells (n = 7). Quantified by Halo software. Mean ± SD is shown. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. Ctrl: vehicle control; MEKi: refametinib; HDACi: domatinostat; MEKi+HDACi: refametinib + domatinostat. Scale bar: μm.

We validated the increased T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in combination-treated tumors by performing mIF for MHCI, GzmB, Cl casp3, and PanCK as a tumor cell marker, along with computational spatial analysis. In tumor regions with high MHCI expression, we observed abundant GzmB+ cells and increased Cl casp3 expression. In contrast, regions with low MHCI expression showed reduced levels of these markers (Fig. 7c). Co-expression analysis revealed that MHCI+ tumor cells significantly expressed more Cl casp3 compared to MHCI− tumor cells (Fig. 7d). Additionally, spatial analysis demonstrated that a higher number of GzmB+ cells were in close proximity (<150 μm radical distance) to MHCI+Cl casp3+ cells compared to MHCI− Cl casp3+ cells (Fig. 7e), supporting the critical role of MHCI in tumor immunogenicity and anti-tumor cytotoxicity in PDAC.

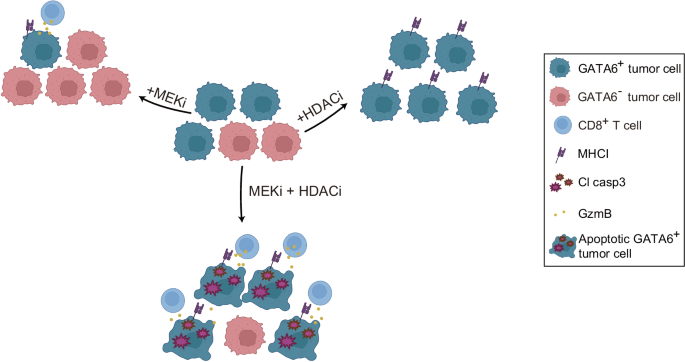

Our results demonstrate that MEKi induces GATA6-dependent MHCI upregulation in tumor cells. However, this effect is diminished by a treatment-induced transition to a different cell state, resulting in the loss of GATA6 expression. Combining MEKi with HDACi preserves the GATA6+ tumor cell population, leading to further enhancement of MHCI expression and increased anti-tumor cytotoxicity (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: GATA6-dependent regulation of tumor MHCI expression and anti-tumor cytotoxicity.

Schematic diagram illustrating how GATA6-dependent MHCI expression in tumor cells is associated with enhanced antitumor cytotoxicity following combined MEK inhibitor (MEKi) and HDAC inhibitor (HDACi) treatment.