Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have become the pantomime villain of modern nutrition. Headlines warn they’re driving obesity, heart disease and even early death; social-media feeds buzz with lists of foods to avoid. The debate reignited in October with Joe Wicks’s Channel 4 documentary, which saw him create the so-called Killer Protein Bar – a stunt designed to expose just how many dubious additives can be used in a product that is not only legal but marketed as “healthy”. Wicks’s bar contained 96 approved ingredients, from sweeteners such as aspartame, to sugar alcohols like xylitol and maltitol, emulsifiers including carboxymethylcellulose, and even carmine, a red dye made from cochineal insects. Each was used within permitted limits, yet together illustrated how highly engineered modern foods can be. The programme’s central message was that the UK now eats more UPFs than any nation except the US – many of them products craftily marketed as nutritious.

For cyclists, this debate hits close to home. Energy gels, carb drinks and recovery shakes – staples of endurance fuelling – fall under the UPF label. So, should we be cutting back, or is the current panic missing the point?

What counts as ultra-processed?

The term ultra-processed food comes from the NOVA classification system, which groups foods by the degree and purpose of industrial processing. “Sports products like gels, bars and recovery shakes often fall into the ultra-processed category under NOVA because they’re made largely from industrially extracted ingredients,” explains Dr Emily Jevons, nutritionist for Team Picnic-PostNL. “Those ingredients are designed to create specific textures, flavours, portability or shelf stability – though some brands use more natural components than others.” Jevons adds that NOVA measures technique, not intent: “A gel exists to deliver rapidly digestible carbohydrates in a compact, portable form during cycling, not to replace a balanced meal. In that sense, the ‘ultra-processed’ label doesn’t really capture its function in an athletic context. It’s a tool, not a dietary pattern.”

You may like

Not all processing is bad news. Cooking, fermenting and freezing all count as processing too – they make food safer or easier to digest. “Ultra-processed” simply goes further, adding ingredients to adjust taste, texture or shelf life. That distinction matters because the UPF category is very broad. Everything from cheap crisps to scientifically formulated recovery powders fits under the UPF umbrella, so sweeping claims that “all UPFs are harmful” don’t hold up to scrutiny.

Most cyclists probably eat what would generally be considered a healthy diet: porridge and coffee before a ride, a post-training omelette, plenty of fruit and veg, the odd pastry at the cafe stop. But if you count the bottles of carb drink, mid-ride bars and post-session shakes, it’s clear that ultra-processed products feature heavily. That’s not because cyclists are careless eaters – quite the opposite. It’s because performance nutrition relies on convenience and digestibility. During long or intense rides, fuel needs to be quickly absorbed, easy on your stomach, and pocket-friendly to carry. In that context, a gel or recovery powder isn’t junk food; it’s part of the equipment list.

But when you’re regularly taking in 300–400g of carbohydrate on the bike – 60–80g an hour, several times a week – there’s not much leeway left for the rest of the day. Keep adding processed carbs off the bike and you risk overshooting your energy needs, while crowding out the whole foods that supply fibre, vitamins and healthy fats. Still, the question remains: does this higher intake of processed products carry the same risks we hear about in the headlines?

Context is king

Most of the alarming headlines about ultra-processed foods come from large population studies linking high consumption to obesity, cardiovascular disease and early mortality. But it’s crucial to look at who those studies were conducted on. “Most of that data comes from general or sedentary populations,” says Jevons. “Those findings are largely driven by over-consumption and the displacement of nutrient-rich foods, not by the mere presence of processing itself.” Cyclists exist in a very different physiological context. “During and after long training sessions, high-glycaemic, rapidly absorbed carbohydrates are exactly what the body needs to maintain glycogen stores, prevent excessive stress responses and support recovery.”

In other words, the same traits that make UPFs problematic for desk workers (high energy density, quick absorption, low fibre) can actually be useful for cyclists. A 2023 paper by Australian researchers found no studies yet examining UPF intake specifically in athletes, and no evidence that sports-nutrition-type UPFs have the same negative effects in sedentary groups. That said, Jevons cautions that “if UPFs dominate the rest of a cyclist’s diet outside training and recovery windows, the same long-term risks could eventually apply. Pattern of intake matters.”

It’s also worth remembering that the public conversation about UPFs can take a psychological toll. The idea that “processed equals bad” doesn’t just oversimplify nutrition – it can fuel guilt, anxiety and disordered eating, and risks stigmatising foods that are affordable and widely eaten, particularly by people on lower incomes or with limited time to cook.

It’s easy to demonise everything that comes in a wrapper, but not all UPFs are created equal. Many are high in added sugar and low in fibre, but others, like recovery powders or high-protein bars, can be valuable tools when used appropriately. “The key is to separate performance nutrition from everyday eating,” says Jevons.

You may like

“During training and racing, gels, chews, isotonic drinks and recovery shakes are effective and safe tools for fuelling and hydration. Outside those contexts, relying on them for convenience meals can crowd out the diversity of micronutrients, fibre and phytonutrients found in whole foods.” Her rule of thumb: if most of your total energy intake comes from minimally processed foods, using engineered products strategically for training and recovery is fine. The problem starts when they replace meals rather than support them.

For endurance riders, convenience isn’t indulgence – it’s a necessity. On the bike, when your heart rate is high and your stomach’s under strain, fuel needs to be portable, palatable and easy to digest. That’s where processed products come into their own. Sports nutrition is, by nature, engineered. Energy gels are designed to provide rapidly absorbed carbohydrates for instant energy. Carb drinks help sustain blood glucose levels on long rides. Recovery shakes provide protein in a form the body can handle when appetite is low. After a big session, sitting down to a full meal isn’t always realistic. A shake or bar can bridge the gap until normal eating feels possible again. In this context, processing isn’t the enemy; it’s part of the performance toolkit. Used thoughtfully and at the right times, these products do what they’re meant to: help you train harder, recover faster and feel stronger on the bike.

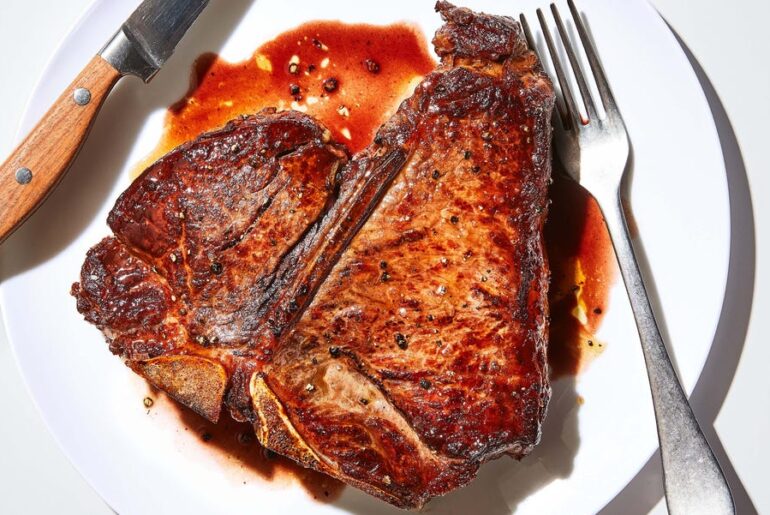

(Image credit: David Lyttleton)

Target your consumption

High training loads don’t give athletes a free pass. Intense exercise protects against some metabolic risks, but it doesn’t erase them entirely. Triathlete Lionel Sanders found this out when blood tests showed pre-diabetic readings after years of relying on sugary convenience foods – proof that performance fitness doesn’t always equal metabolic health. “Cyclists are generally healthier than average,” says Jevons, “but the same principles still apply: nutrient density, variety and balance matter over the long term.” Processed products have their place, but they shouldn’t replace real food. What fuels performance in the short term isn’t always what sustains health over years of riding.

There’s no need to avoid ultra-processed foods completely, but they’re best used with purpose. Gels, bars and shakes have a clear role in training, recovery and competition. They just shouldn’t make up the backbone of your everyday diet. Base regular meals on whole, minimally processed foods: fruit, vegetables, whole grains, pulses, nuts, lean proteins and healthy fats. They underpin everything performance relies on: energy availability, recovery, immune function and resilience.

Barcode-scanning apps now make it easy to check how “processed” a food is. Tools like Zoe, Yuka and FoodSwitch have made the idea of ultra-processing more visible, though they can also oversimplify a complex issue. “Apps like Zoe and Yuka have done a great job raising awareness of food processing,” says Jevons, “but for athletes they can be a bit reductive. Flagging a recovery shake as a ‘red’ food because it contains isolates or stabilisers misses the context of why it’s being used.” For cyclists, these apps are best treated as prompts, not verdicts – reminders to consider overall diet quality rather than moral judgments on individual products. Awareness helps; guilt doesn’t.

On easier rides or rest days, it’s easy to swap processed products for real food. Bananas, dates, or rice cakes with jam work well mid-ride, while smoothies made with yoghurt, fruit and oats make effective recovery options. Some cyclists are also experimenting with honey-based gels as a natural alternative. Early research suggests they provide similar carbohydrate delivery to standard gels, with possible antioxidant benefits – though they can be tricky to carry. The trick is knowing when real food fits and when it doesn’t. For long, low-intensity sessions, whole-food fuel is great. For races or intervals, engineered products still win in terms of speed, portability and stomach comfort.

Ultra-processed foods have become easy targets, but the reality is far more nuanced. For the general population, cutting back makes sense. For cyclists, the key is how and why these products are used. “Used appropriately, these products are part of the solution, not the problem,” says Jevons. “They’re performance tools. The issue comes when they start creeping into every snack and meal.” On the bike, gels, bars and shakes do exactly what they’re meant to: provide fast, accessible fuel when it’s needed most. Off the bike, whole foods should take the lead. The goal isn’t to fear your fuel, but to understand it – because balance matters far more than the label on the wrapper. Processing isn’t the enemy; it’s just another part of the performance equation.

DECODING THE ‘KILLER BAR’ INGREDIENTS

What Joe Wicks’s documentary got cyclists talking about – and what the evidence really says.

Joe Wicks’s Killer Protein Bar raised eyebrows by listing dozens of additives commonly found in processed foods. Many of the same ingredients appear, in much smaller amounts, in everyday sports nutrition. Here’s what the science says:

Aspartame (sweetener): Mainly in diet drinks or protein powders, rarely in gels. Classified by WHO as “possibly carcinogenic”, but safe well below the accepted daily limit. You’d need to consume very large quantities to exceed it.

Sugar alcohols (polyols such as maltitol, xylitol, sorbitol): Common in low-sugar protein bars, not in gels or drinks. Safe, though excess can cause bloating or diarrhoea.

Emulsifiers & stabilisers (lecithin, gums, CMC): Keep powders smooth and bars stable. Lecithin is safe; limited research suggests CMC may alter gut bacteria, but there’s no proven harm in healthy athletes.

Colourings (titanium dioxide, carmine): Mostly cosmetic and now largely phased out. Titanium dioxide is banned in the EU; carmine remains permitted but may trigger rare allergies.

Palm oil and processed fats: Used for texture in some chocolate-coated bars. Research findings are mixed, but there’s little evidence of harm from the small amounts most people eat.

This feature was originally published in the 8 January 2026 print edition of Cycling Weekly magazine – available to buy on the newsstand every Thursday (UK only) while digital versions are available on Apple News and Readly. Subscriptions through Magazine’s Direct.

![[Report] NCN Investment Trends, 2025 recap, 2026 outlook [Report] NCN Investment Trends, 2025 recap, 2026 outlook](https://www.vitaminrush.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/ncn_report_Feb._2026-770x515.png)