Wijsenbeek, M. & Cottin, V. Spectrum of fibrotic lung diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 958–968 (2020).

Plikus, M. V. et al. Fibroblasts: origins, definitions, and functions in health and disease. Cell 184, 3852–3872 (2021).

Henderson, N. C., Rieder, F. & Wynn, T. A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 587, 555–566 (2020).

George, P. M. et al. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: clinical uncertainties, consensus recommendations, and research priorities. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 925–934 (2020).

Lederer, D. J. & Martinez, F. J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1811–1823 (2018).

Wells, A. U., Brown, K. K., Flaherty, K. R., Kolb, M. & Thannickal Victor, J. What’s in a name? That which we call IPF, by any other name would act the same. Eur. Respir. J. 51, 1800692 (2018).

Raghu, G. & Fleming, T. R. Moving forward in IPF: lessons learned from clinical trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 12, 583–585 (2024).

Noble, P. W. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 377, 1760–1769 (2011).

Richeldi, L. et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 2071–2082 (2014).

King, T. E. et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 2083–2092 (2014).

Richeldi, L. et al. Nerandomilast in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 2193–2202 (2025).

Distler, O. et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2518–2528 (2019).

Maher, T. M. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with unclassifiable progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 147–157 (2020).

Flaherty, K. R. et al. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1718–1727 (2019).

Behr, J. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with progressive fibrotic interstitial lung diseases other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (RELIEF): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 9, 476–486 (2021).

Maher, T. M. et al. Nerandomilast in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 2203–2214 (2025).

Adams, T. S. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1983 (2020).

Habermann, A. C. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals profibrotic roles of distinct epithelial and mesenchymal lineages in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1972 (2020).

Franzén, L. et al. Mapping spatially resolved transcriptomes in human and mouse pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 56, 1725–1736 (2024).

Mayr, C. H. et al. Spatial transcriptomic characterization of pathologic niches in IPF. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl5473 (2024).

Sikkema, L. et al. An integrated cell atlas of the lung in health and disease. Nat. Med. 29, 1563–1577 (2023).

Tsukui, T. et al. Collagen-producing lung cell atlas identifies multiple subsets with distinct localization and relevance to fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 1920 (2020).

Tsukui, T., Wolters, P. J. & Sheppard, D. Alveolar fibroblast lineage orchestrates lung inflammation and fibrosis. Nature 631, 627–634 (2024). This paper shows that injury-induced pathogenic fibroblasts arise from alveolar fibroblasts after lung injury. A highly orchestrated sequence of fibroblast state transitions, driven by inflammatory and profibrotic cues, is required for effective regeneration.

Valenzi, E. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and myofibroblasts in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78, 1379–1387 (2019).

Melms, J. C. et al. A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Nature 595, 114–119 (2021).

Vannan, A. et al. Spatial transcriptomics identifies molecular niche dysregulation associated with distal lung remodeling in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 57, 647–658 (2025). This study provides a spatially resolved, single-cell map of the human fibrotic lung, revealing niche-specific dysregulation in advanced pulmonary fibrosis.

Fabre, T. et al. Identification of a broadly fibrogenic macrophage subset induced by type 3 inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 8, eadd8945 (2023).

Schupp, J. C. et al. Integrated single-cell atlas of endothelial cells of the human lung. Circulation 144, 286–302 (2021).

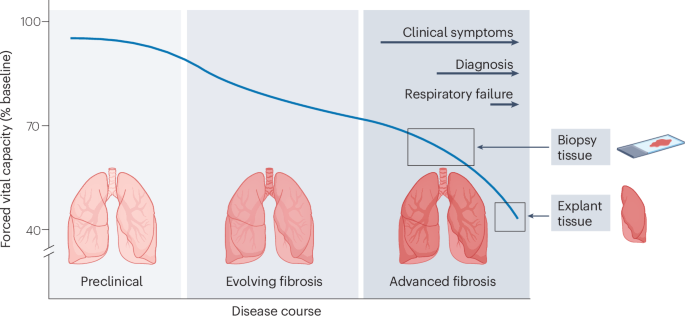

Park, J. H. et al. Mortality and risk factors for surgical lung biopsy in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 31, 1115–1119 (2007).

Martin, P., Pardo-Pastor, C., Jenkins, R. G. & Rosenblatt, J. Imperfect wound healing sets the stage for chronic diseases. Science 386, eadp2974 (2024).

Younesi, F. S., Miller, A. E., Barker, T. H., Rossi, F. M. V. & Hinz, B. Fibroblast and myofibroblast activation in normal tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 617–638 (2024).

Hinz, B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 526–537 (2007).

Hinz, B. & Lagares, D. Evasion of apoptosis by myofibroblasts: a hallmark of fibrotic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 16, 11–31 (2020). In this seminal review, the authors describe that myofibroblasts are primed for apoptosis but evade programmed cell death through upregulation of pro-survival pathways.

Jun, J.-I. & Lau, L. F. The matricellular protein CCN1 induces fibroblast senescence and restricts fibrosis in cutaneous wound healing. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 676–685 (2010).

Demaria, M. et al. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev. Cell 31, 722–733 (2014).

Kisseleva, T. et al. Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during regression of liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9448–9453 (2012).

Hecker, L., Jagirdar, R., Jin, T. & Thannickal, V. J. Reversible differentiation of myofibroblasts by MyoD. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 1914–1921 (2011).

Konkimalla, A. et al. Transitional cell states sculpt tissue topology during lung regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 30, 1486–1502.e9 (2023). This study reveals Runx1 as a driver of profibrotic fibroblast states. Runx1 deletion in PDGFRα+ fibroblasts improves fibrosis but disrupts ECM organization and lung architecture.

Jones, D. L. et al. An injury-induced mesenchymal–epithelial cell niche coordinates regenerative responses in the lung. Science 386, eado5561 (2024). This study uncovers how alveolar fibroblast plasticity regulates lung repair by modulating stem cell competition between airway-derived and alveolar-derived epithelial progenitors.

Plikus, M. V. et al. Regeneration of fat cells from myofibroblasts during wound healing. Science 355, 748–752 (2017).

Merkt, W., Zhou, Y., Han, H. & Lagares, D. Myofibroblast fate plasticity in tissue repair and fibrosis: deactivation, apoptosis, senescence and reprogramming. Wound Repair Regen. 29, 678–691 (2021).

Desmoulière, A., Redard, M., Darby, I. & Gabbiani, G. Apoptosis mediates the decrease in cellularity during the transition between granulation tissue and scar. Am. J. Pathol. 146, 56–66 (1995).

Distler, J. H. W. et al. Shared and distinct mechanisms of fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 15, 705–730 (2019).

Zepp, J. A. & Morrisey, E. E. Cellular crosstalk in the development and regeneration of the respiratory system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 551–566 (2019).

Nowarski, R., Jackson, R. & Flavell, R. A. The stromal intervention: regulation of immunity and inflammation at the epithelial–mesenchymal barrier. Cell 168, 362–375 (2017).

Basil, M. C. et al. The cellular and physiological basis for lung repair and regeneration: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell 26, 482–502 (2020).

Greicius, G. et al. PDGFRα+ pericryptal stromal cells are the critical source of Wnts and RSPO3 for murine intestinal stem cells in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E3173–e3181 (2018).

Shoshkes-Carmel, M. et al. Subepithelial telocytes are an important source of Wnts that supports intestinal crypts. Nature 557, 242–246 (2018).

Zacharias, W. J. et al. Regeneration of the lung alveolus by an evolutionarily conserved epithelial progenitor. Nature 555, 251–255 (2018).

Nabhan, A. N., Brownfield, D. G., Harbury, P. B., Krasnow, M. A. & Desai, T. J. Single-cell Wnt signaling niches maintain stemness of alveolar type 2 cells. Science 359, 1118–1123 (2018). In this paper, the authors show that fibroblast-derived WNT signals support AT2 stem cell self-renewal, whereas injury-induced autocrine WNT signals expand the progenitor pool.

Zepp, J. A. et al. Distinct mesenchymal lineages and niches promote epithelial self-renewal and myofibrogenesis in the lung. Cell 170, 1134–1148.e10 (2017).

Fernanda de Mello Costa, M., Weiner, A. I. & Vaughan, A. E. Basal-like progenitor cells: a review of dysplastic alveolar regeneration and remodeling in lung repair. Stem Cell Rep. 15, 1015–1025 (2020).

Zuo, W. et al. p63+Krt5+ distal airway stem cells are essential for lung regeneration. Nature 517, 616–620 (2015).

Choi, J. et al. Inflammatory signals induce AT2 cell-derived damage-associated transient progenitors that mediate alveolar regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 27, 366–382.e7 (2020).

Narasimhan, H. et al. An aberrant immune–epithelial progenitor niche drives viral lung sequelae. Nature 634, 961–969 (2024). In this study, the authors demonstrate that IFNγ and TNF derived from CD8+ T cells stimulate macrophages to continuously release IL-1β. This drives maintenance of dysplastic epithelial cell progenitors and lung fibrosis after COVID-19 infection.

Vaughan, A. E. et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature 517, 621–625 (2015).

Weiner, A. I. et al. Np63 drives dysplastic alveolar remodeling and restricts epithelial plasticity upon severe lung injury. Cell Rep. 41, 111805 (2022).

Taylor, M. S. et al. A conserved distal lung regenerative pathway in acute lung injury. Am. J. Pathol. 188, 1149–1160 (2018).

Heinzelmann, K. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies G-protein coupled receptor 87 as a basal cell marker expressed in distal honeycomb cysts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 59, 2102373 (2022).

Davidson, S. et al. Fibroblasts as immune regulators in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 704–717 (2021).

Alexandre, Y. O. & Mueller, S. N. Splenic stromal niches in homeostasis and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 705–719 (2023).

Krishnamurty, A. T. & Turley, S. J. Lymph node stromal cells: cartographers of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 21, 369–380 (2020).

Fletcher, A. L., Malhotra, D. & Turley, S. J. Lymph node stroma broaden the peripheral tolerance paradigm. Trends Immunol. 32, 12–18 (2011).

Lee, J. W. et al. Peripheral antigen display by lymph node stroma promotes T cell tolerance to intestinal self. Nat. Immunol. 8, 181–190 (2007).

Fletcher, A. L. et al. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells directly present peripheral tissue antigen under steady-state and inflammatory conditions. J. Exp. Med. 207, 689–697 (2010).

Malhotra, D. et al. Transcriptional profiling of stroma from inflamed and resting lymph nodes defines immunological hallmarks. Nat. Immunol. 13, 499–510 (2012).

Astarita, J. L. et al. The CLEC-2–podoplanin axis controls the contractility of fibroblastic reticular cells and lymph node microarchitecture. Nat. Immunol. 16, 75–84 (2015).

Assen, F. P. et al. Multitier mechanics control stromal adaptations in the swelling lymph node. Nat. Immunol. 23, 1246–1255 (2022).

Fletcher, A. L., Acton, S. E. & Knoblich, K. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 350–361 (2015).

Scandella, E. et al. Restoration of lymphoid organ integrity through the interaction of lymphoid tissue–inducer cells with stroma of the T cell zone. Nat. Immunol. 9, 667–675 (2008).

Onder, L. et al. IL-7-producing stromal cells are critical for lymph node remodeling. Blood 120, 4675–4683 (2012).

Foster, D. S. et al. Multiomic analysis reveals conservation of cancer-associated fibroblast phenotypes across species and tissue of origin. Cancer Cell 40, 1392–1406.e7 (2022).

Pentimalli, T. M. et al. Combining spatial transcriptomics and ECM imaging in 3D for mapping cellular interactions in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Syst. 16, 101261 (2025).

Öhlund, D. et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 214, 579–596 (2017).

Gao, Y. et al. Cross-tissue human fibroblast atlas reveals myofibroblast subtypes with distinct roles in immune modulation. Cancer Cell 42, 1764–1783.e10 (2024).

Biffi, G. et al. IL1-induced JAK/STAT signaling is antagonized by TGFβ to shape CAF heterogeneity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 9, 282–301 (2019).

Croft, A. P. et al. Distinct fibroblast subsets drive inflammation and damage in arthritis. Nature 570, 246–251 (2019).

Boyd, D. F. et al. Exuberant fibroblast activity compromises lung function via ADAMTS4. Nature 587, 466–471 (2020).

Korsunsky, I. et al. Cross-tissue, single-cell stromal atlas identifies shared pathological fibroblast phenotypes in four chronic inflammatory diseases. Med 3, 481–518.e14 (2022).

Dobie, R. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics uncovers zonation of function in the mesenchyme during liver fibrosis. Cell Rep. 29, 1832–1847.e8 (2019).

Ramachandran, P. et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature 575, 512–518 (2019).

Morse, C. et al. Proliferating SPP1/MERTK-expressing macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 54, 1802441 (2019).

Reyfman, P. A. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 199, 1517–1536 (2019).

Kuppe, C. et al. Decoding myofibroblast origins in human kidney fibrosis. Nature 589, 281–286 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat. Immunol. 20, 928–942 (2019).

Ma, F. et al. Single cell and spatial sequencing define processes by which keratinocytes and fibroblasts amplify inflammatory responses in psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 14, 3455 (2023).

Wohlfahrt, T. et al. PU.1 controls fibroblast polarization and tissue fibrosis. Nature 566, 344–349 (2019).

Fang, Y. et al. RUNX2 promotes fibrosis via an alveolar-to-pathological fibroblast transition. Nature 640, 221–230 (2025). This study shows that the transcription factor Runx2 mediates the conversion of alveolar fibroblasts into profibrotic CTHRC1+POSTN+ myofibroblasts. Conditional genetic deletion of Runx2 in alveolar fibroblasts mitigates pulmonary fibrosis.

Lingampally, A. et al. Evidence for a lipofibroblast-to-Cthrc1+ myofibroblast reversible switch during the development and resolution of lung fibrosis in young mice. Eur. Respir. J. 65, 2300482 (2025).

Mayr, C. H. et al. Sfrp1 inhibits lung fibroblast invasion during transition to injury-induced myofibroblasts. Eur. Respir. J. 63, 2301326 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Distinct mural cells and fibroblasts promote pathogenic plasma cell accumulation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 65, 2401114 (2025).

Ewing-Crystal, N. A. et al. Dynamic fibroblast–immune interactions shape recovery after brain injury. Nature 646, 934–944 (2025).

Amuso, V. M. et al. Fibroblast-mediated macrophage recruitment supports acute wound healing. J. Invest. Dermatol. 145, 1781–1797.e8 (2025).

Guo, J. L. et al. Histological signatures map anti-fibrotic factors in mouse and human lungs. Nature 641, 993–1004 (2025).

Kanisicak, O. et al. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nat. Commun. 7, 12260 (2016).

Wynn, T. A. & Vannella, K. M. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity 44, 450–462 (2016).

Buechler, M. B., Fu, W. & Turley, S. J. Fibroblast–macrophage reciprocal interactions in health, fibrosis, and cancer. Immunity 54, 903–915 (2021).

Wynn, T. A., Chawla, A. & Pollard, J. W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature 496, 445–455 (2013).

Behmoaras, J., Mulder, K., Ginhoux, F. & Petretto, E. The spatial and temporal activation of macrophages during fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 25, 816–830 (2025).

Duffield, J. S. et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 56–65 (2005).

Aran, D. et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 20, 163–172 (2019).

Amrute, J. M. et al. Targeting immune–fibroblast cell communication in heart failure. Nature 635, 423–433 (2024).

Misharin, A. V. et al. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2387–2404 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Circuit design features of a stable two-cell system. Cell 172, 744–757.e17 (2018).

Adler, M. et al. Principles of cell circuits for tissue repair and fibrosis. iScience 23, 100841 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Profibrotic effect of IL-17A and elevated IL-17RA in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease support a direct role for IL-17A/IL-17RA in human fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 316, L487–L497 (2019).

Chrysanthopoulou, A. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote differentiation and function of fibroblasts. J. Pathol. 233, 294–307 (2014).

Gregory, A. D. et al. Neutrophil elastase promotes myofibroblast differentiation in lung fibrosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 98, 143–152 (2015).

Wilson, M. S. et al. Bleomycin and IL-1β-mediated pulmonary fibrosis is IL-17A dependent. J. Exp. Med. 207, 535–552 (2010).

Mi, S. et al. Blocking IL-17A promotes the resolution of pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis via TGF-β1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Immunol. 187, 3003–3014 (2011).

Carter, H. et al. CD103+ dendritic cell-fibroblast crosstalk via TLR9, TDO2, and AHR signaling drives lung fibrogenesis. JCI Insight 10, e177072 (2025).

Lu, Y. Z. et al. CGRP sensory neurons promote tissue healing via neutrophils and macrophages. Nature 628, 604–611 (2024). This study shows that ablation of sensory nociceptors impairs skin wound repair and muscle regeneration after acute tissue injury. It demonstrates that the nociceptor-derived neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibits recruitment and accelerates removal of pro-inflammatory myeloid cells, promoting tissue repair.

Almanzar, N. et al. Vagal TRPV1+ sensory neurons protect against influenza virus infection by regulating lung myeloid cell dynamics. Sci. Immunol. 10, eads6243 (2025).

Hiroki, C. H. et al. Nociceptor neurons suppress alveolar macrophage-induced Siglec-F+ neutrophil-mediated inflammation to protect against pulmonary fibrosis. Immunity 58, 2054–2068.e6 (2025). This study shows that vagal TRPV1+ nociceptors protect against experimental pulmonary fibrosis by restraining alveolar macrophage-derived VIP. Loss of TRPV1+ nociceptors results in increased macrophage-derived VIP and downstream induction of TGFβ1-mediated recruitment of pro-inflammatory neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular trap formation.

Li, W. et al. A brain-to-lung signal from GABAergic neurons to ADRB2+ interstitial macrophages promotes pulmonary inflammatory responses. Immunity 58, 2069–2085.e9 (2025).

Gieseck, R. L., Wilson, M. S. & Wynn, T. A. Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 62–76 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Neuropilin-1 mediates lung tissue-specific control of ILC2 function in type 2 immunity. Nat. Immunol. 23, 237–250 (2022).

Otaki, N. et al. Activation of ILC2s through constitutive IFNγ signaling reduction leads to spontaneous pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 14, 8120 (2023).

Cui, G. et al. CD45 alleviates airway inflammation and lung fibrosis by limiting expansion and activation of ILC2s. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2215941120 (2023).

Nakatsuka, Y. et al. Profibrotic function of pulmonary group 2 innate lymphoid cells is controlled by regnase-1. Eur. Respir. J. 57, 2000018 (2021).

Dahlgren, M. W. et al. Adventitial stromal cells define group 2 innate lymphoid cell tissue niches. Immunity 50, 707–722.e6 (2019).

Cautivo, K. M. et al. Interferon gamma constrains type 2 lymphocyte niche boundaries during mixed inflammation. Immunity 55, 254–271.e7 (2022). This study shows that, in type 2 immune responses, ILC2s migrate to de novo parenchymal sites near alveoli via IL-33-induced upregulation of trafficking-associated S1P receptors.

He, Y. et al. Mechanics-activated fibroblasts promote pulmonary group 2 innate lymphoid cell plasticity propelling silicosis progression. Nat. Commun. 15, 9770 (2024).

Jowett, G. M. et al. ILC1 drive intestinal epithelial and matrix remodelling. Nat. Mater. 20, 250–259 (2021).

Geng, Y. et al. PD-L1 on invasive fibroblasts drives fibrosis in a humanized model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 4, e125326 (2019).

Cui, L. et al. Activation of JUN in fibroblasts promotes pro-fibrotic programme and modulates protective immunity. Nat. Commun. 11, 2795 (2020). This work demonstrates an exhausted-like phenotype in CD8+ T cells in explanted lung tissue from patients with IPF.

Wernig, G. et al. Unifying mechanism for different fibrotic diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4757–4762 (2017).

Celada, L. J. et al. PD-1 up-regulation on CD4+ T cells promotes pulmonary fibrosis through STAT3-mediated IL-17A and TGF-β1 production. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaar8356 (2018).

Yadav, S. et al. Reactivation of CTLA4-expressing T cells accelerates resolution of lung fibrosis in a humanized mouse model. J. Clin. Investig. 135, e181775 (2025).

Martin, O. P. et al. Single-cell atlas of human liver and blood immune cells across fatty liver disease stages reveals distinct signatures linked to liver dysfunction and fibrogenesis. Nat. Immunol. 26, 1596–1611 (2025).

Pfister, D. et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature 592, 450–456 (2021).

Mariathasan, S. et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554, 544–548 (2018).

Krishnamurty, A. T. et al. LRRC15+ myofibroblasts dictate the stromal setpoint to suppress tumour immunity. Nature 611, 148–154 (2022).

Sato, Y., Silina, K., van den Broek, M., Hirahara, K. & Yanagita, M. The roles of tertiary lymphoid structures in chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19, 525–537 (2023).

Sato, Y. et al. Heterogeneous fibroblasts underlie age-dependent tertiary lymphoid tissues in the kidney. JCI Insight 1, e87680 (2016).

Nayar, S. et al. Immunofibroblasts are pivotal drivers of tertiary lymphoid structure formation and local pathology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 13490–13497 (2019). This work demonstrates that perivascular fibroblasts acquire features of FRCs, including expression of the homeostatic cytokines CCL21, CCL19 and CXCL13, and depend on lymphotoxin-β signalling between stromal and immune cells.

Denton, A. E. et al. Type I interferon induces CXCL13 to support ectopic germinal center formation. J. Exp. Med. 216, 621–637 (2019).

Jacquelot, N., Tellier, J., Nutt, S. l. & Belz, G. T. Tertiary lymphoid structures and B lymphocytes in cancer prognosis and response to immunotherapies. Oncoimmunology 10, 1900508 (2021).

Farr, A. G. et al. Characterization and cloning of a novel glycoprotein expressed by stromal cells in T-dependent areas of peripheral lymphoid tissues. J. Exp. Med. 176, 1477–1482 (1992).

Kratz, A., Campos-Neto, A., Hanson, M. S. & Ruddle, N. H. Chronic inflammation caused by lymphotoxin is lymphoid neogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 183, 1461–1472 (1996).

Kamiya, M. et al. Immune mechanisms in fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Cell 187, 3506–3530 (2024).

Taillé, C. et al. Identification of periplakin as a new target for autoreactivity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183, 759–766 (2011).

Koether, K. et al. Autoantibodies are associated with disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 61, 2102381 (2023).

Ganeshan, K. & Chawla, A. Metabolic regulation of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 609–634 (2014).

Selvarajah, B., Azuelos, I., Anastasiou, D. & Chambers, R. C. Fibrometabolism — an emerging therapeutic frontier in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Signal. 14, eaay1027 (2021).

Noom, A., Sawitzki, B., Knaus, P. & Duda, G. N. A two-way street — cellular metabolism and myofibroblast contraction. npj Regen. Med. 9, 15 (2024).

Xie, N. et al. Glycolytic reprogramming in myofibroblast differentiation and lung fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 192, 1462–1474 (2015).

Selvarajah, B. et al. mTORC1 amplifies the ATF4-dependent de novo serine–glycine pathway to supply glycine during TGF-β(1)-induced collagen biosynthesis. Sci. Signal. 12, eaav3048 (2019).

Andrianifahanana, M. et al. Profibrotic up-regulation of glucose transporter 1 by TGF-β involves activation of MEK and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 pathways. FASEB J. 30, 3733–3744 (2016).

Kottmann, R. M. et al. Lactic acid is elevated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and induces myofibroblast differentiation via pH-dependent activation of transforming growth factor-β. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 740–751 (2012).

Nigdelioglu, R. et al. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β promotes de novo serine synthesis for collagen production. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 27239–27251 (2016).

Ge, J. et al. Glutaminolysis promotes collagen translation and stability via α-ketoglutarate-mediated mTOR activation and proline hydroxylation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 58, 378–390 (2018).

Bai, L. et al. Glutaminolysis epigenetically regulates antiapoptotic gene expression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 60, 49–57 (2019). This paper shows that glutamine metabolism promotes resistance to apoptosis in IPF fibroblasts via epigenetic reprogramming.

Mamazhakypov, A., Schermuly, R. T., Schaefer, L. & Wygrecka, M. Lipids — two sides of the same coin in lung fibrosis. Cell Signal. 60, 65–80 (2019).

Sosulski, M. L. et al. Deregulation of selective autophagy during aging and pulmonary fibrosis: the role of TGFβ1. Aging Cell 14, 774–783 (2015).

Robinson, C. M., Neary, R., Levendale, A., Watson, C. J. & Baugh, J. A. Hypoxia-induced DNA hypermethylation in human pulmonary fibroblasts is associated with Thy-1 promoter methylation and the development of a pro-fibrotic phenotype. Respir. Res. 13, 74 (2012).

Senavirathna, L. K. et al. Hypoxia induces pulmonary fibroblast proliferation through NFAT signaling. Sci. Rep. 8, 2709 (2018).

Taylor, C. T., Doherty, G., Fallon, P. G. & Cummins, E. P. Hypoxia-dependent regulation of inflammatory pathways in immune cells. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 3716–3724 (2016).

Mirchandani, A. S., Sanchez-Garcia, M. A. & Walmsley, S. R. How oxygenation shapes immune responses: emerging roles for physioxia and pathological hypoxia. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 25, 161–177 (2025).

Mirchandani, A. S. et al. Hypoxia shapes the immune landscape in lung injury and promotes the persistence of inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 23, 927–939 (2022).

Santos, A. & Lagares, D. Matrix stiffness: the conductor of organ fibrosis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 20, 2 (2018).

Parker, M. W. et al. Fibrotic extracellular matrix activates a profibrotic positive feedback loop. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1622–1635 (2014).

Liu, F. et al. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression. J. Cell Biol. 190, 693–706 (2010).

Herrera, J., Henke, C. A. & Bitterman, P. B. Extracellular matrix as a driver of progressive fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 128, 45–53 (2018).

Walker, C. J. et al. Nuclear mechanosensing drives chromatin remodelling in persistently activated fibroblasts. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 1485–1499 (2021).

Novak, C. M., Wheat, J. S., Ghadiali, S. N. & Ballinger, M. N. Mechanomemory of pulmonary fibroblasts demonstrates reversibility of transcriptomics and contraction phenotypes. Biomaterials 314, 122830 (2025).

Balestrini, J. L., Chaudhry, S., Sarrazy, V., Koehler, A. & Hinz, B. The mechanical memory of lung myofibroblasts. Integr. Biol. 4, 410–421 (2012).

Wong, V. W. et al. Focal adhesion kinase links mechanical force to skin fibrosis via inflammatory signaling. Nat. Med. 18, 148–152 (2012). Data from this study suggest that physical force modulates wound healing and fibrosis via paracrine fibroblast–macrophage crosstalk, implicating a direct link between mechanobiology and inflammation during wound healing.

Du, H. et al. Tuning immunity through tissue mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 174–188 (2023).

Huse, M. Mechanical forces in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 679–690 (2017).

Atcha, H. et al. Mechanically activated ion channel Piezo1 modulates macrophage polarization and stiffness sensing. Nat. Commun. 12, 3256 (2021).

Meli, V. S. et al. YAP-mediated mechanotransduction tunes the macrophage inflammatory response. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb8471 (2020).

Chakraborty, M. et al. Mechanical stiffness controls dendritic cell metabolism and function. Cell Rep. 34, 108609 (2021).

Solis, A. G. et al. Mechanosensation of cyclical force by PIEZO1 is essential for innate immunity. Nature 573, 69–74 (2019). This study shows that cyclical hydrostatic pressure initiates a pulmonary inflammatory response via the mechanically activated ion channel PIEZO1. These data illustrate how immune activation thresholds are modulated by the mechanical properties of the lungs.

Saitakis, M. et al. Different TCR-induced T lymphocyte responses are potentiated by stiffness with variable sensitivity. eLife 6, e23190 (2017).

Meng, K. P., Majedi, F. S., Thauland, T. J. & Butte, M. J. Mechanosensing through YAP controls T cell activation and metabolism. J. Exp. Med. 217, e20200053 (2020).

Shaheen, S. et al. Substrate stiffness governs the initiation of B cell activation by the concerted signaling of PKCβ and focal adhesion kinase. eLife 6, e23060 (2017).

Sutherland, T. E., Dyer, D. P. & Allen, J. E. The extracellular matrix and the immune system: a mutually dependent relationship. Science 379, eabp8964 (2023).

Penkala, I. J. et al. Age-dependent alveolar epithelial plasticity orchestrates lung homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1775–1789.e5 (2021).

Shiraishi, K. et al. Biophysical forces mediated by respiration maintain lung alveolar epithelial cell fate. Cell 186, 1478–1492.e15 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis is caused by elevated mechanical tension on alveolar stem cells. Cell 180, 107–121.e17 (2020). In this study, the authors describe a direct mechanistic link among impaired AT2 cell regeneration, increased mechanical tension and a subpleural-to-central pattern of progressive pulmonary fibrosis.

Liu, Z. et al. MAPK-mediated YAP activation controls mechanical-tension-induced pulmonary alveolar regeneration. Cell Rep. 16, 1810–1819 (2016).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Persistence of a regeneration-associated, transitional alveolar epithelial cell state in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 934–946 (2020).

Enomoto, Y. et al. Autocrine TGF-β-positive feedback in profibrotic AT2-lineage cells plays a crucial role in non-inflammatory lung fibrogenesis. Nat. Commun. 14, 4956 (2023). This paper shows that bleomycin induces AT2 cells to enter an intermediate transition state enriched for SASP-related factors including TGFβ. This establishes TGFβ-mediated autocrine feedback loops and drives myofibroblast activation.

Hoffman, E. T. et al. Aberrant intermediate alveolar epithelial cells promote pathogenic activation of lung fibroblasts in preclinical fibrosis models. Nat. Commun. 16, 8710 (2025).

Martinez, F. J. et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3, 17074 (2017).

Moss, B. J., Ryter, S. W. & Rosas, I. O. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 17, 515–546 (2022).

Farhat, A. et al. An aging bone marrow exacerbates lung fibrosis by fueling profibrotic macrophage persistence. Sci. Immunol. 10, eadk5041 (2025). Bone marrow transplantation from aged donors reveals a role for the aged haematopoietic compartment in promoting persistent profibrotic macrophage populations and exacerbating fibrosis.

Sano, S. et al. Hematopoietic loss of Y chromosome leads to cardiac fibrosis and heart failure mortality. Science 377, 292–297 (2022).

Rossi, D. J. et al. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9194–9199 (2005).

Mann, M. et al. Heterogeneous responses of hematopoietic stem cells to inflammatory stimuli are altered with age. Cell Rep. 25, 2992–3005.e5 (2018).

Niec, R. E., Rudensky, A. Y. & Fuchs, E. Inflammatory adaptation in barrier tissues. Cell 184, 3361–3375 (2021).

Netea, M. G., Quintin, J. & van der Meer, J. W. M. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe 9, 355–361 (2011).

Netea, M. G. et al. Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 375–388 (2020).

Naik, S. et al. Inflammatory memory sensitizes skin epithelial stem cells to tissue damage. Nature 550, 475–480 (2017). This study expands the concept of trained immunity to epithelial stem cells, demonstrating that prior inflammation enhances epithelial responsivity after wounding.

Frišcic, J. et al. The complement system drives local inflammatory tissue priming by metabolic reprogramming of synovial fibroblasts. Immunity 54, 1002–1021.e10 (2021). This study shows that synovial fibroblasts display elements of inflammatory ‘memory-like’ responses in vivo using adoptive transfer models.

Bian, X. et al. Epigenetic memory of radiotherapy in dermal fibroblasts impairs wound repair capacity in cancer survivors. Nat. Commun. 15, 9286 (2024).

Larsen, S. B. et al. Establishment, maintenance, and recall of inflammatory memory. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1758–1774.e8 (2021).

Falvo, D. J. et al. A reversible epigenetic memory of inflammatory injury controls lineage plasticity and tumor initiation in the mouse pancreas. Dev. Cell 58, 2959–2973.e7 (2023).

Del Poggetto, E. et al. Epithelial memory of inflammation limits tissue damage while promoting pancreatic tumorigenesis. Science 373, eabj0486 (2021).

Levra Levron, C. et al. Tissue memory relies on stem cell priming in distal undamaged areas. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 740–753 (2023).

Crowley, T., Buckley, C. D. & Clark, A. R. Stroma: the forgotten cells of innate immune memory. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 193, 24–36 (2018).

Sohn, C. et al. Prolonged tumor necrosis factor α primes fibroblast-like synoviocytes in a gene-specific manner by altering chromatin. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 86–95 (2015).

Klein, K. et al. The epigenetic architecture at gene promoters determines cell type-specific LPS tolerance. J. Autoimmun. 83, 122–133 (2017).

Kamada, R. et al. Interferon stimulation creates chromatin marks and establishes transcriptional memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E9162–E9171 (2018).

Álvarez, D. et al. IPF lung fibroblasts have a senescent phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 313, L1164–l1173 (2017).

Schafer, M. J. et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat. Commun. 8, 14532 (2017).

Schuliga, M. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the senescent phenotype of IPF lung fibroblasts. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 22, 5847–5861 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Inhibition of mechanosensitive signaling in myofibroblasts ameliorates experimental pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 123, 1096–1108 (2013).

Lagares, D. et al. Targeted apoptosis of myofibroblasts with the BH3 mimetic ABT-263 reverses established fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaal3765 (2017).

Cooley, J. C. et al. Inhibition of antiapoptotic BCL-2 proteins with ABT-263 induces fibroblast apoptosis, reversing persistent pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 8, e163762 (2023).

Bühling, F. et al. Altered expression of membrane-bound and soluble CD95/Fas contributes to the resistance of fibrotic lung fibroblasts to FasL induced apoptosis. Respir. Res. 6, 37 (2005).

Im, J., Kim, K., Hergert, P. & Nho, R. S. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts become resistant to Fas ligand-dependent apoptosis via the alteration of decoy receptor 3. J. Pathol. 240, 25–37 (2016).

Wang, T.-W. et al. Blocking PD-L1–PD-1 improves senescence surveillance and ageing phenotypes. Nature 611, 358–364 (2022). This study demonstrates that CD8+ T cells are involved in cytotoxicity against senescent fibroblasts and that PDL1 expression in senescent cells results in escape from T cell immunity.

Pereira, B. I. et al. Senescent cells evade immune clearance via HLA-E-mediated NK and CD8+ T cell inhibition. Nat. Commun. 10, 2387 (2019).

Krizhanovsky, V. et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 134, 657–667 (2008).

Naik, S. & Fuchs, E. Inflammatory memory and tissue adaptation in sickness and in health. Nature 607, 249–255 (2022).

Reyes, N. S. et al. Sentinel p16(INK4a+) cells in the basement membrane form a reparative niche in the lung. Science 378, 192–201 (2022).

Ritschka, B. et al. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype induces cellular plasticity and tissue regeneration. Genes Dev. 31, 172–183 (2017).

Aghajanian, H. et al. Targeting cardiac fibrosis with engineered T cells. Nature 573, 430–433 (2019).

Sobecki, M. et al. Vaccination-based immunotherapy to target profibrotic cells in liver and lung. Cell Stem Cell 29, 1459–1474.e9 (2022).

Nabhan, A. N. et al. Targeted alveolar regeneration with frizzled-specific agonists. Cell 186, 2995–3012.e15 (2023).

Liakouli, V., Ciancio, A., Del Galdo, F., Giacomelli, R. & Ciccia, F. Systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease: unmet needs and potential solutions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 20, 21–32 (2024).

Shaw, M., Collins, B. F., Ho, L. A. & Raghu, G. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 24, 1–16 (2015).

Grunewald, J. et al. Sarcoidosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 5, 45 (2019).

Barnes, H. et al. Diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in adults: a position statement from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology 29, 1023–1046 (2024).

Regev, A. et al. The human cell atlas. eLife 6, e27041 (2017).

Krausgruber, T. et al. Structural cells are key regulators of organ-specific immune responses. Nature 583, 296–302 (2020).

Muhl, L. et al. Single-cell analysis uncovers fibroblast heterogeneity and criteria for fibroblast and mural cell identification and discrimination. Nat. Commun. 11, 3953 (2020).

Buechler, M. B. et al. Cross-tissue organization of the fibroblast lineage. Nature 593, 575–579 (2021).

Elmentaite, R., Domínguez Conde, C., Yang, L. & Teichmann, S. A. Single-cell atlases: shared and tissue-specific cell types across human organs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 395–410 (2022).

Tsukui, T. & Sheppard, D. Stromal heterogeneity in the adult lung delineated by single-cell genomics. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 328, C1964–C1972 (2025).

Madissoon, E. et al. A spatially resolved atlas of the human lung characterizes a gland-associated immune niche. Nat. Genet. 55, 66–77 (2023).

Stuart, T. & Satija, R. Integrative single-cell analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 257–272 (2019).

Basil, M. C. & Morrisey, E. E. Lung regeneration: a tale of mice and men. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 100, 88–100 (2020).

Jenkins, R. G. et al. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop report: use of animal models for the preclinical assessment of potential therapies for pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 56, 667–679 (2017).

Naikawadi, R. P. et al. Telomere dysfunction in alveolar epithelial cells causes lung remodeling and fibrosis. JCI Insight 1, e86704 (2016).

Povedano, J. M., Martinez, P., Flores, J. M., Mulero, F. & Blasco, M. A. Mice with pulmonary fibrosis driven by telomere dysfunction. Cell Rep. 12, 286–299 (2015).

Yao, C. et al. Senescence of alveolar type 2 cells drives progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 203, 707–717 (2020).

Redente, E. F. et al. Loss of Fas signaling in fibroblasts impairs homeostatic fibrosis resolution and promotes persistent pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 6, e141618 (2020).

Wendisch, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers profibrotic macrophage responses and lung fibrosis. Cell 184, 6243–6261.e27 (2021).