New research reveals that the heart, brain, nervous, and immune systems are all connected during heart attacks.

A leading cause of death worldwide

Cardiovascular diseases are the world’s leading cause of death, with more than four out of five of these deaths caused by heart attacks and strokes.

In a heart attack, clogged arteries restrict blood flow, and oxygen supply to heart tissues is reduced, resulting in cell death and necrosis.

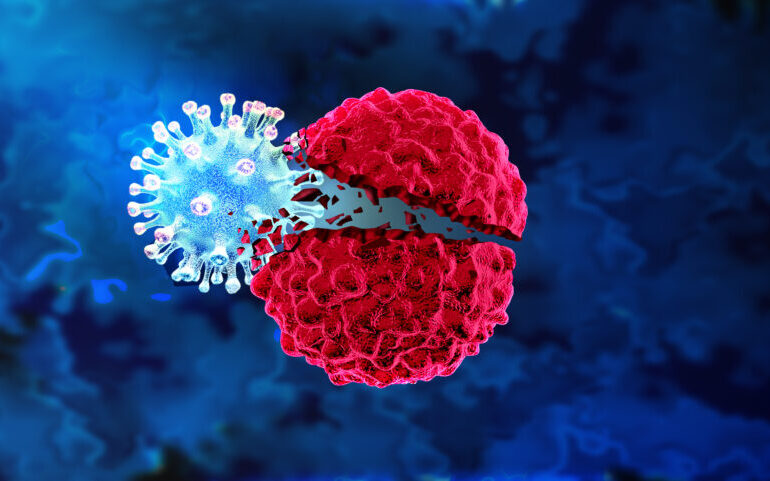

Conventional approaches to understanding and treating heart attacks focus on the heart as an isolated organ, but new research from the University of California San Diego proposes that heart attacks can be characterized though a “triple node” lens that incorporates connections between the heart, brain and immune system.

“We’re flipping the switch on heart attack research to show that it’s not just the heart itself that is involved,” said Professor Vineet Augustine, one of the authors of the new research.

Heart–brain signaling

Communication between the heart and the brain is essential for maintaining cardiovascular health and is mediated by intricate neural, immune, and endocrine pathways.

Neurons in the vagus nerve or the dorsal root ganglia, movement of immune cells and molecules, and autonomic nervous system signaling enable communication from the heart to the brain and vice versa.

After a heart attack, neural responses, including increased sensory and sympathetic signaling, influence cardiac inflammation and immune system activity.

Increased sympathetic signaling from the brain after a heart attack contributes to ventricular remodeling, which can further impair cardiac function and lead to heart failure.

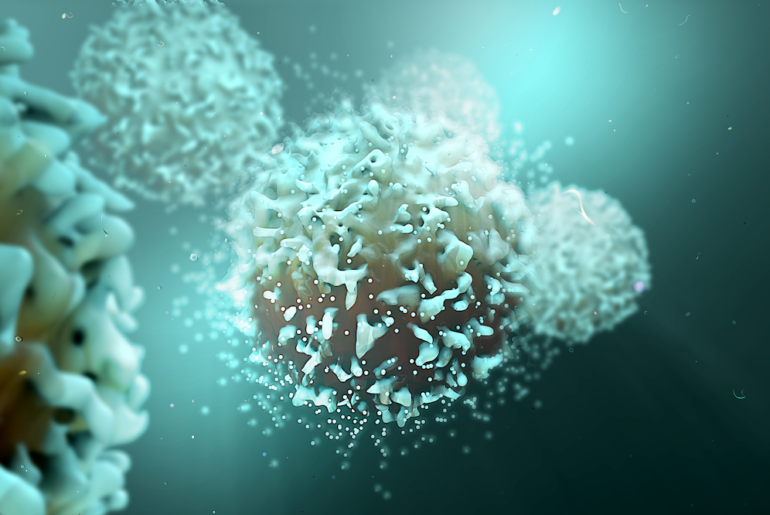

The researchers propose that the overactivation of the immune system in response to a heart attack likely worsens the damage.

Using single-cell RNA sequencing in mice, the researchers set out to map the connections between the heart, brain, and immune system.

Three nodes behind heart attack signaling

The study identified a subset of vagal sensory neurons (VSNs) that expressed transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1), which could be involved in sensing myocardial injury and subsequent ventricular remodeling. These neurons increased in number after a heart attack in mouse models. The researchers also mapped the TRPV1-expressing VSN fibers as they shifted to increased innervation in the heart—indicating that TRPV1 VSNs may be a key component of the sensory pathway that responds to heart injury.

The researchers specifically removed this subset of VSNs, which reduced post-heart attack inflammation and the severity of cardiac dysfunction, as well as enhancing recovery.

They propose that TRPV1-expressing VSNs form one of the three nodes involved in bi-directional communication between the heart, brain, and immune systems following heart attacks.

Changes in heart tissues

Spatial transcriptomics and single-nuclei sequencing were then used to map the changes in heart cell composition after a heart attack to reveal how VSNs influence cardiomyocytes and angiogenesis.

When TRPV1 VSNs were removed, a significant shift in cardiomyocyte subtypes was observed, particularly in the infarct zone—tissue that was damaged in the heart attack—which was smaller in the models with TRPV1 VSNs ablated.

Increased neuronal activity was linked to ventricular remodeling

Following a heart attack, neuronal activity in the hypothalamus increases, specifically in angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1aR)-expressing neurons, which increases sympathetic nervous system signaling and leads to ventricular remodeling. When TRPV1 VSNs were ablated, this neuronal activity was reduced, indicating that TRPV1 VSNs interact with angiotensin II receptor type 1-expressing neurons.

The researchers also illustrated that inhibiting AT1aR-expressing neurons alleviated some of the damage from a heart attack.

AT1aR-expressing neurons in the hypothalamus were therefore proposed to be another node involved in heart attacks.

Inflammation in the ganglia

The researchers also noted that immune signaling mediated by interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and sympathetic innervation from the superior cervical ganglia increased after a heart attack. They identified that the sympathetic signaling directly innervated the heart, contributing to ventricular remodeling.

The increase in IL-1β signaling from the superior cervical ganglia was also found to be sufficient to reduce cardiac function. Blocking this signaling pathway reduced inflammation, suggesting that the superior cervical ganglia plays a key role in adverse cardiac outcomes after a heart attack.

New treatments for heart attacks

The three nodes involved in a bi-directional communication loop between the brain and the heart following a heart attack were identified as: TRPV1 VSNs, AT1aR-expressing neurons in the hypothalamus, and sympathetic and inflammatory signaling from the superior cervical ganglion.

“Blocking this heart-brain-neuroimmune system was shown to stop the spread of the disease,” said Dr. Saurabh Yadav, who also worked on the research. “If you think of a heart attack as the epicenter, the blockage of the signals stopped the spread of the injury.”

Further understanding of the three-node loop system behind heart attacks could help to spur new treatments that leverage the connections between the heart, brain, and immune systems.

“Current treatments for heart attacks focus on repairing the heart, including bypass surgery, angioplasty, and blood thinners, which are all invasive,” said Augustine. “This research is showing that perhaps by manipulating the immune system we can drive a therapeutic response.”

Reference: Yadav S, Ninh VK, Lovelace JW, et al. A triple-node heart-brain neuroimmune loop underlying myocardial infarction. Cell. 2026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.12.058

This article is a rework of a press release issued by the University of California San Diego. Material has been edited for length and content.