A new study has found that gut bacteria can inject proteins into human cells to trigger immune responses. The discovery enhances understanding of gut-immune interactions, where microbes directly modulate pathways alongside metabolites.

The research points out that this communication mechanism between gut bacteria and human cells has not yet been recorded, which helps explain the gut microbiome’s role in inflammatory diseases.

The researchers identified that many harmless bacteria possess type III secretion systems, which are syringe-like structures that inject bacterial proteins into human cells. This structure was previously thought to exist only in pathogens.

Nutrition Insight speaks with the study’s corresponding author about the implications of this discovery and its potential to influence the design of microbial communities for therapeutic use.

The team mapped out over 1,000 bacterial proteins and human protein interactions, revealing their impact on immune regulation and metabolism, which may contribute to chronic intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease patients

Sparking innovative microbiome interventions

Professor Pascal Falter-Braun, director of the Institute of Network Biology, says the research discovery brings a new dimension to gut-immune interactions.

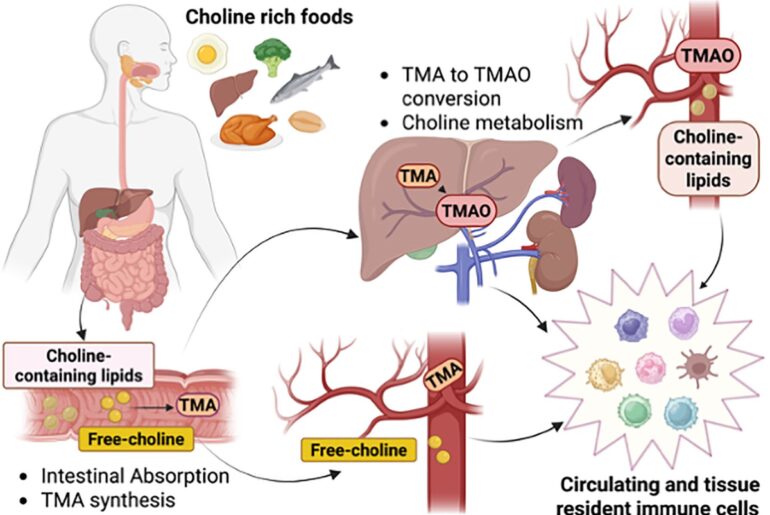

Gut bacteria use protein effectors to directly manipulate human immune pathways, shifting understandings from metabolite-based interactions to molecular communication.“It suggests that, beyond metabolites and immune sensing, some microbes may directly modulate host immune pathways at the protein level. That said, it is far too early to draw conclusions that would immediately affect the composition of microbiome-targeted supplements.”

Gut bacteria use protein effectors to directly manipulate human immune pathways, shifting understandings from metabolite-based interactions to molecular communication.“It suggests that, beyond metabolites and immune sensing, some microbes may directly modulate host immune pathways at the protein level. That said, it is far too early to draw conclusions that would immediately affect the composition of microbiome-targeted supplements.”

“In the midterm, however, these findings may help us better distinguish which bacterial strains have specific, context-dependent effects on the immune system,” he notes. “This could open the door to identifying immune-beneficial microbes. These act not primarily through metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, but through more targeted modulation of host signaling pathways, such as promoting anti-inflammatory responses under defined conditions.”

Additionally, Falter-Braun says the discovery may spark designs of microbial communities with a specific combination of strains that produce stronger or more durable effects than individuals alone.

Although these approaches require significantly more mechanistic and in vivo research, they also offer promising, more precise directions for microbiome-based interventions.

Impacts on immune pathways

The study in Nature Microbiology identified bacterial protein effectors that influenced central immune signaling pathways, such as the NF-kB and MAP kinase, well-established in research. “We have also shown that NF-kB activity is changed and that this leads to altered immune responses,” says Falter-Braun.

“However, these observations about the actual impact of effectors in human cells are only an initial view, as we have only looked at a small subset of immune pathways to demonstrate that immune responses are altered by bacterial proteins at all. Understanding the complexity of this, including which pathways are modulated more strongly, is a key question that must be addressed now.”

He points out another interesting observation about gram-negative bacteria. These cause public health problems, as their hard outer shell results in higher antibiotic resistance, and they inject bacterial proteins into cells. They alter immune responses to gram-positive bacteria, a group of beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus.

“Thus, the human host appears to be used in the fight between microbes among each other. This may be potentially interesting for commercial applications, as establishing new beneficial microbes is notoriously challenging. If we speculate, it could be that effectors play a role in the underlying difficulties,” says Falter-Braun.

The Type III secretion system is a syringe-like structure that gut bacteria use to inject immune-modulating proteins directly into human intestinal cells.“On the metabolic side, we noticed a strong targeting of fatty acid metabolism, but we have not done functional studies yet, which are an important next step.”

The Type III secretion system is a syringe-like structure that gut bacteria use to inject immune-modulating proteins directly into human intestinal cells.“On the metabolic side, we noticed a strong targeting of fatty acid metabolism, but we have not done functional studies yet, which are an important next step.”

Gaps in translating findings to human health

The team says they have only scratched the surface by exposing the microbiome’s influence on immunity and, likely, human health.

“While our study reveals a previously unrecognized way in which gut bacteria can directly interact with human cells, several important gaps remain before these findings can be translated into clinical insights,” says Falter-Braun.

“We still need to understand under which conditions commensal bacteria activate these injection systems in the human gut, how often protein delivery occurs in vivo, and whether and which of these interactions are causal drivers of disease.”

He continues to explain that linking specific bacterial effectors to measurable effects will need longitudinal studies and experimental models. These would need to capture host genetics, microbial context, and environmental influences.

“Addressing these questions will be essential to move from molecular maps to actionable health insights.”

Implications for inflammatory diseases

Falter-Braun reports that patients with Crohn’s disease had more genes encoding the bacterial effector proteins, suggesting direct protein delivery from gut bacteria to human cells may contribute to chronic intestinal inflammation.

“On a practical level, this may reinforce the motivation for Crohn’s disease patients to ‘garden their microbiome’ to reduce the prevalence of the gram-negative proteobacteria and increase the abundance of beneficial microbes.”

“On a deeper level, the observations from our study point to opposing mechanisms that favor the emergence of ulcerative colitis versus Crohn’s disease in different individuals. This has not been appreciated by the scientific community so far and opens the door for studies that will help us understand both diseases and the contributing factors on a much deeper level,” he says.

Additionally, the team is highly interested in learning about the role of bacterially injected proteins in Crohn’s disease and whether they have a protective effect in ulcerative colitis.

Next steps

The researchers say their study has advanced understanding of the microbiome by shifting research from correlation to causation.

“The next steps are to move from mapping interactions to understanding functions. We are already using these bacterial effectors in follow-up studies to examine their biochemical effects in human cells, including their influence on signaling pathways and cellular responses,” says Falter-Braun.

“An important near-term goal is to test these proteins across different human cell types to assess tissue-specific effects. Ultimately, the most informative experiments will involve more complex systems, such as disease models and human organoids, which better capture tissue architecture and physiological context.”

He notes that these investigations are technically challenging. Before they can be broadly applied, a clearer understanding of bacterial effectors’ functions on tissues and health conditions is required.

“Building this functional overview will be a critical foundation for more targeted and translational studies that may eventually inform microbiome-based therapeutic strategies,” concludes Falter-Braun.

In other emerging gut health research, Nutrition Insight recently spoke with a Cambridge University researcher who found that healthy people’s gut microbiomes consistently have higher levels of the bacterial group CAG-170 than those with diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and obesity. The study revealed the importance of understanding the “hidden microbiome” to foster new therapeutics.