Beauty and fashion influencer Eni Popoola first learned she’d been deepfaked the way many creators do: from her audience. A YouTube ad sent by a follower featured her face and her voice, promoting an online course she had never heard of.

“People were sending screenshots saying, ‘Hey, there’s this video of you, and we obviously know it’s not you, because this is not something that you would talk about,’” Popoola said.

She’s far from alone, as the experience of finding one’s AI doppelganger — promoting unknown supplements, self-help content or beauty products — is becoming increasingly commonplace in the creator economy. The phenomenon is just part of a wider wave of virtual characters appearing to shill affiliate links from TikTok Shop and Amazon for brands like Cerave or Tarte.

“We’re at the point now where you can generate something that’s essentially undetectable,” said Kyle Dulay, founder of influencer marketing platform Collabstr.

Most brands remain wary about the prospect of creating content using artificial influencers. A recent Collabstr study of 40,000 advertisers and 100,000 creators on its platform found that 86 percent of respondents did not want to work with virtual influencers, a figure up 30 percent from 2024.

But the ubiquity of affiliate linking has incentivised enterprising individuals and companies to head to platforms like Sora, Nano Banana or Kling to generate fake influencers. TikTok, Instagram and YouTube have been inundated with people charging for paid “courses” on how to create the most realistic-looking influencers with the right lighting and skin texture, promising thousands of dollars a month in earnings.

Many of these tutorials include tips on how to create AI-generated posts that slip past platforms’ required disclosure rules, showing that the extent of how many are succeeding is difficult to measure. Wonderskin, a top-selling brand on TikTok known for its viral blue peel-off lip stain, has detected TikTok Shop-linked posts made with AI, but none of them show characters actually applying the product.

“The technology hasn’t been good enough to create realistic demonstrations or product applications,” said Wonderskin chief executive Michael Malinsky, who is skeptical that AI influencer content can make as much money as promised. “If they were making so many thousands of dollars generating affiliate commissions, why are they selling courses about how to generate affiliate commissions?”

But brands are prepared for that to change as technology improves. Dieux founder Charlotte Palermino posted on Instagram that she discovered many AI influencers listed in an affiliate report, and shared an account’s AI-generated TikTok video of a Dieux product, calling for tighter regulation of AI content.

“If TikTok can’t fix this, real creators will not be creating as much anymore. I can’t compete with somebody who doesn’t sleep and just posts videos nonstop,” said Palermino.

Artificial Expertise

AI likenesses have popped up for social media personalities of all follower counts, from reality stars to microinfluencers. Medical professionals like dermatologists and plastic surgeons have become especially frequent targets, in part because of the trust audiences place in them.

Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Dr. Andrew Cohen first learned he’d been impersonated after a friend sent him an Instagram video appearing to show Cohen promoting a supplement.

“I clicked the link and thought, ‘No, that’s not me,’” Cohen said. “Also, I’m way better looking.”

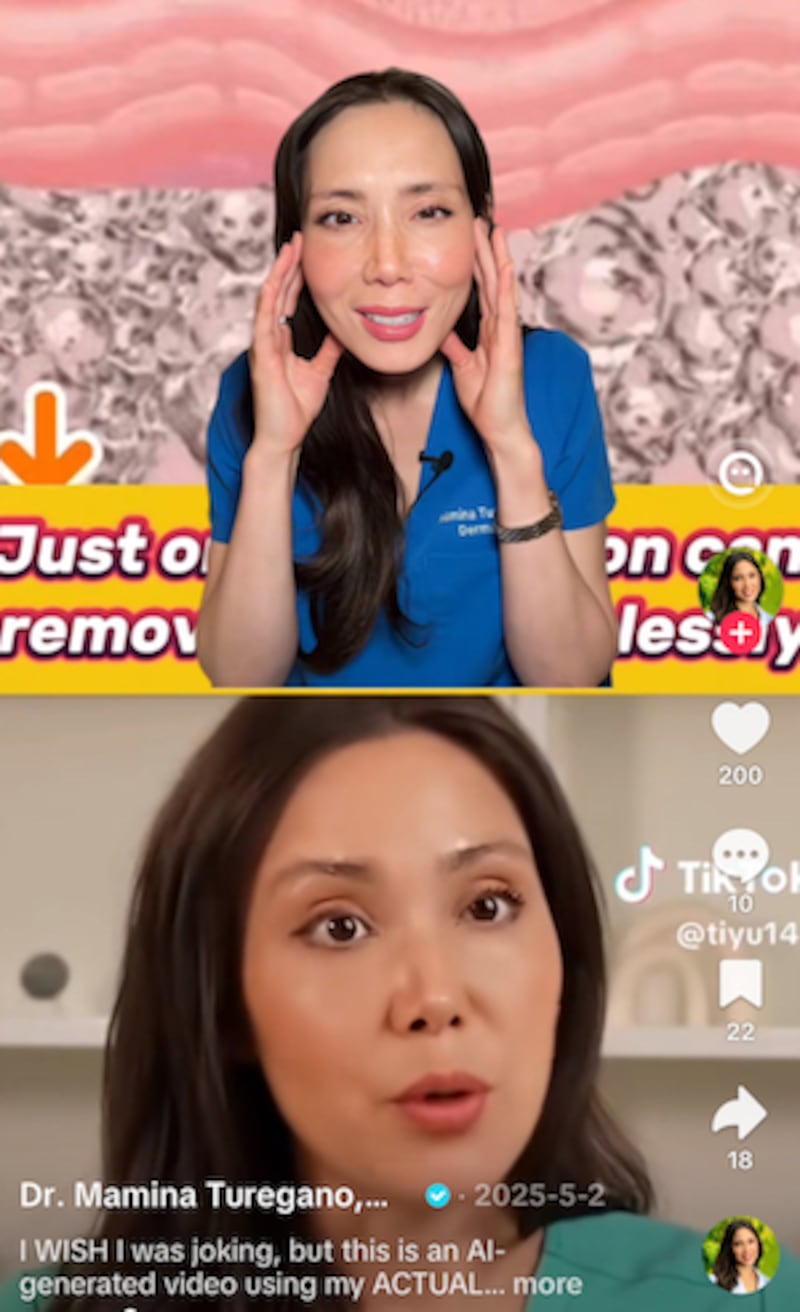

Others who have come across deepfakes include plastic surgeon Dr. Daniel Barrett, who was impersonated in an AI-generated post claiming to be a dentist, as well as dermfluencers Dr. Michelle Henry, Dr. Brooke Jeffy and Dr. Mamina Turegano. Doctors are fighting back by posting warnings, such as Turegano, who created a video calling out an AI deepfake video of her promoting a purported wart and skin tag removal cream.

Dermatologist Mamina Turegano reacts to an AI deepfake using her likeness to sell a skin cream. (TikTok)

Dermatologist Mamina Turegano reacts to an AI deepfake using her likeness to sell a skin cream. (TikTok)

Reporting to platforms is influencers’ fastest recourse in these situations, as impersonations and lack of disclosure of AI content are banned by Meta, YouTube and TikTok policies. But finding the culprits is difficult. Popoola succeeded in reporting the deepfake of herself to YouTube and seeing it removed, but she has not been able to identify who was behind it.

Influencers are worried that these incidents harm their credibility. “Let’s say someone buys something with my recommendation that’s AI, and then they get hurt,” said Cohen. “Now they’re going to sue me for the fact they got sick from this medication … and I have to prove it wasn’t me.” His team has tried to report the video to Meta, but it remains available, while the culprit has been difficult to find.

Beyond doctors, other types of fake AI experts are being used to bring negative reviews of brands and promote less well-known competitors.

The US brand Grande Cosmetics has come across AI-generated content giving its products poor reviews while promoting rival brands. In one TikTok video with more than 400,000 views, a clearly artificial “lash tech” claims its lash serum caused eye irritation while recommending a competitor’s product. Two accounts featuring dubious creators — “Glowwithmia” and “Skincarewithaimee” — give lacklustre reviews to skincare brands at Sephora and Target before praising products from a brand called Jiyu. (Jiyu did not respond to questions on who created the accounts.)

“I’m seeing a lot of brand-equity-destructive behavior,” said Wojtek Kokoszka, chief executive of influencer marketing platform Mention Me. “And some of it may very well be done by competitors.”

Mainstream Potential

It’s not just unknown or small brands being sold by AI influencers. An AI ad for L’Oréal-owned Cerave on TikTok directs to a listing on its official Amazon shop, while products from mainstream brands can be found in AI accounts’ TikTok Shop showcases. An account called “CowboyMom91” featuring a blonde woman filming in her kitchen contains videos disclosed as AI-generated with watermarks from the AI platform Sora, along with TikTok Shop links to brands including Kitsch, Tarte and Color Wow.

An ad on TikTok featuring an AI-generated influencer linking to buy a Cerave product on Amazon. (TikTok)

An ad on TikTok featuring an AI-generated influencer linking to buy a Cerave product on Amazon. (TikTok)

These videos could proliferate as venture capital funds pour money into startups heavily focused on AI-generated influencer content. Founded by former Snapchat executive Alex Mashrabov, AI video platform Higgsfield has raised $130 million and is often linked in promotions for tutorials on how to make lifelike AI influencers. Doublespeed, an AI influencer company that received $1 million in funding from Andreessen Horowitz, operates over 2,000 AI influencer accounts on TikTok alone, according to its 21-year-old founder Zuhair Lakhani, who said clients included unnamed supplement and beauty brands.

“For people who aren’t deeply online — especially older audiences — it’s incredibly easy to get tricked,” said Lakhani.

Some accounts have seemed to fool, or at least win over, audiences. One called “Baddie Betty,” a self-proclaimed 82-year-old, is seen doing viral TikTok dances in designer outfits and unboxing “gifted” products l. With over 719,000 followers, it is not disclosed as AI. While earlier videos of “Baddie Betty,” offering sassy soundbites on relationships were recognised as AI content, newer, slightly more realistic videos feature countless comments of effusive praise.

Still, experts argue that consumers remain generally averse to AI-generated beauty reviews if they know it’s not showing the product in action on a real human.

“The moment people realize it’s not another human being talking to them, something breaks psychologically,” said Kokoszka. “The half-life of the virtual influencer is very short.”

Sign up toThe Business of Beauty newsletter, your complimentary, must-read source for the day’s most important beauty and wellness news and analysis.