Researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, have discovered that immune cells known as macrophages remain poised to fight repeat infections due to the persistent presence of signaling molecules left behind during previous infections. The study, to be published February 18 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), provides surprising new details about how the body’s innate immune system retains memories of previous immune threats, and suggests new ways to reduce the activity of misprogrammed macrophages that contribute to autoimmune diseases such as lupus and arthritis.

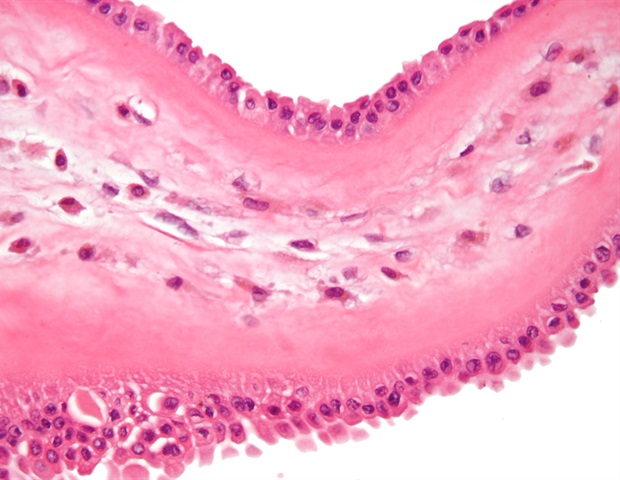

Macrophages patrol the body’s tissues for potential threats such as invading microbes or cancerous cells. Macrophages can engulf and kill these threats, as well as send signals to other immune cells to join the fight, thereby promoting either inflammation or tissue repair.

In recent years, researchers have found that macrophages retain memories of previous encounters that allow them to mount a stronger response if a threat should reoccur. In the body, macrophage memory formation depends on a signaling molecule, or cytokine, known as interferon gamma. During an initial immune response, interferon gamma prompts macrophages to unwrap specific sections of their DNA to form specialized “enhancer” domains that promote gene activity. These newly formed enhancers leave hundreds of immune response genes poised for action, ready to be quickly and strongly activated if the threat should reoccur. But how macrophages maintain this memory for long periods after their initial exposure to interferon gamma was unknown.

Our new findings suggest that these changes in macrophages are actually readily reversible and do not inherently encode immune memory. Instead, the cells are dependent on ongoing signaling from interferon gamma sequestered at or near the macrophage cell surface.”

Professor Alexander Hoffmann, senior author of the JEM study

Pioneered by lead author Aleksandr Gorin, an infectious disease physician and a postdoctoral researcher in the Hoffmann laboratory, the study reports that human macrophages temporarily exposed to interferon gamma form thousands of new enhancers that persist for many days and strengthen the cells’ subsequent response to bacterial molecules. The researchers discovered, however, that small amounts of interferon gamma remain stuck to the macrophages and their immediate surroundings even after most of the cytokine has been removed.

Signals from this residual interferon gamma are required to maintain the macrophages’ memory: when Gorin inhibited the persistent interferon gamma signals, macrophages erased their enhancers and reduced their response to bacterial molecules.

“We suggest that acute immune activity within a tissue in response to infection or injury may “stain” the tissue with cytokines and that ongoing signaling from these molecules contributes to lasting changes in tissue resident macrophages,” Gorin says. Hoffmann adds “Our observation that the interferon gamma–induced memory state is pharmacologically reversible raises the possibility that at least some trained immune states can be pharmacologically erased or modified by blocking cytokine signaling pathways.”

Erasing the memory of macrophages could, for example, be therapeutically useful in autoimmune disease where macrophages have become aberrantly trained to attack the body’s own, healthy tissues, such as in lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or type 1 diabetes.

Source:

Journal reference:

Gorin, A., et al. (2026). IFNγ-induced memory in human macrophages is sustained by the durability of cytokine signaling itself. Journal of Experimental Medicine. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20250976. https://rupress.org/jem/article/223/4/e20250976/281507/IFN-induced-memory-in-human-macrophages-is