Listen to this article

Estimated 4 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by AI-based technology. Mispronunciations can occur. We are working with our partners to continually review and improve the results.

Salt River First Nation in the N.W.T. is expanding its wellness efforts by transforming a former correctional facility into a healing space.

The new wellness centre hosts sharing circles, workshops and land-based programming rooted in culture and lived experience. It is located in the building that housed the men’s corrections centre until 2024.

Salt River First Nation officially opened the facility on Nov. 3 and said the transformation from correctional centre to healing centre is just the beginning of a broader push toward community-driven wellness.

This week, the centre welcomed Indigenous hip-hop artist Paul Sawan, also known as K.A.S.P. — Keeping Alive Stories for the People — for a three-day “tradition over addiction” workshop.

The workshop focuses on reclaiming your life, escaping harmful patterns and rebuilding through culture, sobriety and practical tools for change, K.A.S.P. said.

He began his own healing journey in 2009 and, after getting clean and sober, turned that experience into a career helping others do the same. His message centres on self-worth and personal responsibility as the starting point for healing.

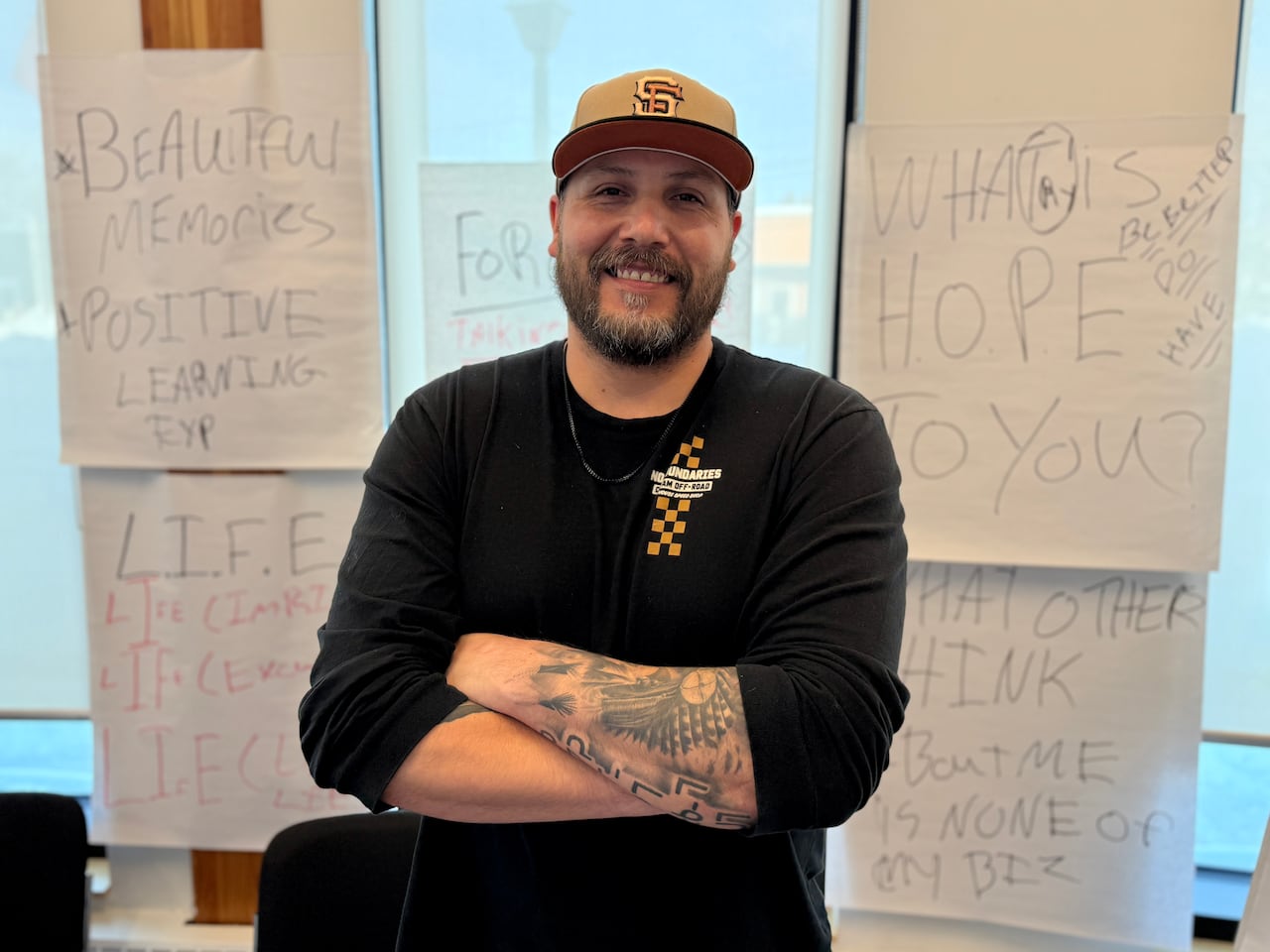

Hip-hop artist K.A.S.P. said many Indigenous communities are still carrying the effects of drugs, alcohol, gang and lateral violence rooted in residential schools. (Carla Ulrich/CBC)

Hip-hop artist K.A.S.P. said many Indigenous communities are still carrying the effects of drugs, alcohol, gang and lateral violence rooted in residential schools. (Carla Ulrich/CBC)

“Your story matters, and who you are makes a difference. You have greatness in you if you decide to embrace it,” he said. “It all starts with sobriety. It all starts with culture. It all starts with tradition.”

K.A.S.P., who has been touring his workshop for years, said he’s seeing a shift across communities, with younger and older generations choosing sobriety and reconnecting with their roots.

“Just to see people getting sober, especially our young people, that’s huge,” he said. “And it makes my heart smile. It just shows that I’m living my purpose.”

He said the work matters because many Indigenous communities are still carrying the effects of drugs, alcohol, gang and lateral violence rooted in residential schools. While support programs exist, few are grounded in Indigenous perspectives and lived experience.

He said the most powerful moments come when he sees generations connecting — elders, adults and youth opening up emotionally and spiritually in the same space.

For Salt River men’s health and wellness coordinator, Chris Waniandy, who has been sober for six years, the workshop is part of a broader effort to create space for people who have long carried their struggles alone.

Waniandy recently earned his diploma in addictions and community health. He said his focus now is on building practical supports that make it easier for people to seek help close to home.

Salt River’s men’s health and wellness coordinator Chris Waniandy has been sober for 6 years. He said it’s important for men to have a safe space to talk about their struggles. (Carla Ulrich/CBC)

Salt River’s men’s health and wellness coordinator Chris Waniandy has been sober for 6 years. He said it’s important for men to have a safe space to talk about their struggles. (Carla Ulrich/CBC)

“People tend to want to talk to people with lived experience,” he said. “[I’ve] lost way too many people to addiction, suicide. And you know, if I can help one person, that’s more than enough.”

One of the biggest gaps he sees in the community is the lack of support specifically for men. He said that too often there’s nowhere for men to go to talk openly about what they’re carrying.

And that stigma prevents many men from speaking about trauma, addiction and grief, he said, so he wants to create a space where the burden doesn’t have to be carried alone.

“I want people to know that they’re cared for, they’re seen, they’re heard,” he said. “Don’t be scared to open up. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. You’re not a burden. Just reach out before it’s too late.”

Leading the centre is wellness coordinator Mavis Moberly, who has worked in social services and community healing for more than 30 years.

Mavis Moberly has worked in social services and community healing for more than 30 years. She is the wellness coordinator at the new centre. (Submitted by Mavis Moberly)

Mavis Moberly has worked in social services and community healing for more than 30 years. She is the wellness coordinator at the new centre. (Submitted by Mavis Moberly)

She said the centre offers stability for people at some of their most vulnerable moments. Whether someone is returning from treatment or waiting for a bed to open, the centre provides a place to regroup, reflect and begin planning next steps.

Staff will help individuals navigate housing, connect to resources and access cultural supports. The approach, she said, is shaped by generations of disrupted teachings and the ongoing impacts of residential schools, with an emphasis on restoring culture and choice.

“I missed out on a lot of teachings I would have had if I’d been raised with my people,” she said. “How can we teach our children what we didn’t have? I work with people to figure out what’s missing and how culture can help fill those gaps.”