What’s a side chain that’s curvy gotta do with scurvy? Proline isn’t *pro*-lines & it’s definitely *anti* α-helix! But it’s a pro at being structurally awkward! Proline (Pro, P) may just be the wackiest protein letter (amino acid)… It has a secondary instead of a primary amine group but it gets genetically coded for & inserted into growing protein chains just like any other. It’s just… special…

blog form: http://bit.ly/prolinestuff

It’s Day 10 of #20DaysOfAminoAcids – the bumbling biochemist’s version of an advent calendar. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. There are 20 (common) genetically-specified ones, each with a generic backbone with to allow for linking up through peptide bonds to form chains (polypeptides) that fold up into functional proteins, as well as unique side chains (aka “R groups” that stick off like charms from a charm bracelet). Each day I’m going to bring you the story of one of these “charms” – what we know about it and how we know about it, where it comes from, where it goes, and outstanding questions nobody knows.

More on amino acids in general here http://bit.ly/aminoacidstoproteins, but the basic overview is:

amino acids have generic “amino” (NH₃⁺/NH₂) & “carboxyl” (COOH/COO⁻) groups that let them link up together through peptide bonds (N links to C, H₂O lost, and the remaining “residual” parts are called residues). The reason for the “2 options” in parentheses is that these groups’ protonation state (how many protons (H⁺ ) they have) depends on the pH (which is a measure of how many free H⁺ are around to take).

Those generic parts are attached to a central “alpha carbon” (Ca), which is also attached to one of 20 unique side chains (“R groups”) which have different properties (big, small, hydrophilic (water-loving), hydrophobic (water-avoided), etc.) & proteins have different combos of them, so the proteins have different properties. And we can get a better appreciation and understanding of proteins if we look at those letters. So, today let’s look at Proline (Pro, P).

Biochemically and functionally, it’s an amino acid – it serves as a protein letter (albeit a quirky one), getting coded for by 3-letter RNA “codons” (in the case of Pro, CCU, CCA, CCC, & CCG) and added to a growing chain during protein making, just like any other. But because the N is hooked up to 2 carbons in the free form, it’s called a “secondary amine” instead of a “primary amine” (where the N’s only attached to one non-H).

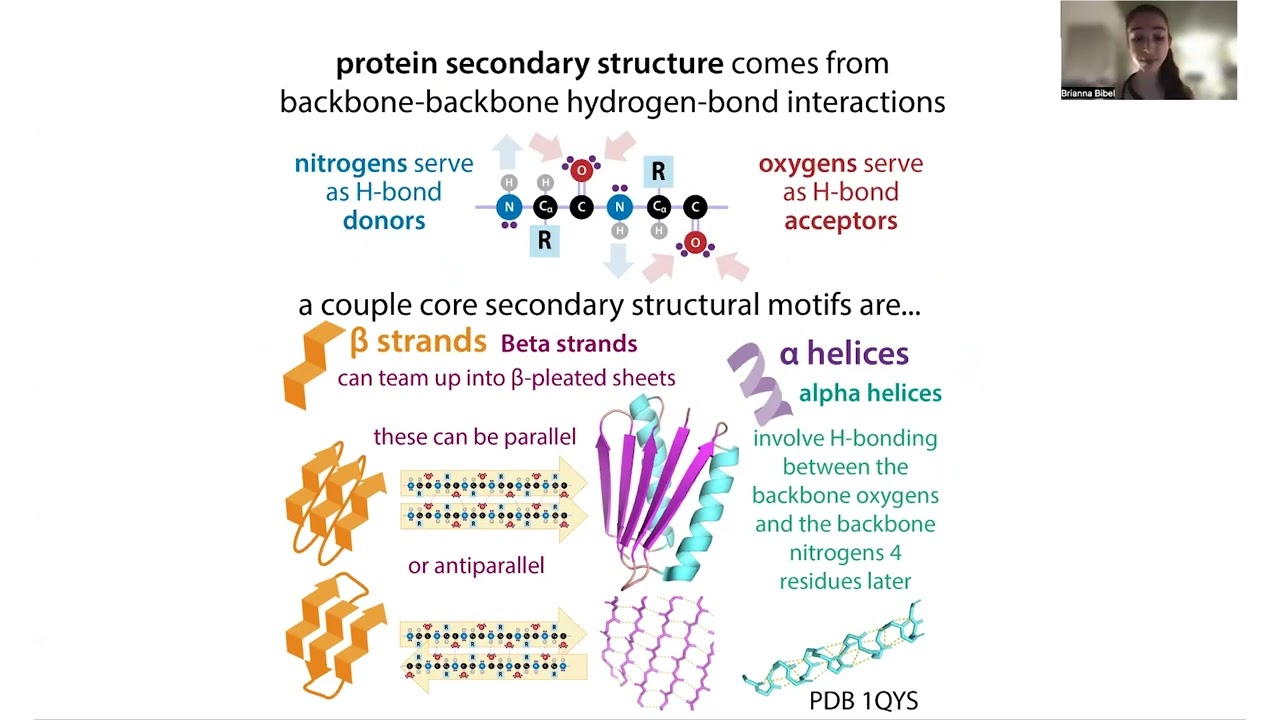

All the other amino acids’ side chains (R groups) only connect to the “generic” backbone at Cα. BUT proline’s side chain comes off Cα, loops around & connects to backbone’s nitrogen, “kicking out” an H – a really important one! Normally when amino acids link together (through peptide bonds), this N still has that H so it can act as a H-donor in non covalent hydrogen bonds with the Os of other amino acids’ backbones to form secondary structures like a helices & beta strands. Oh jargon-dy-gook… Let me explain…

Basically, atoms (like individual C’s, H’s, O’s, & N’s) are really tiny, but they’re made up of even tinier parts called “subatomic particles,” which include electrons, protons, and neutrons. Electrons are negatively-charged subatomic particles that whizz around in “electron clouds” around a dense central core called the atomic nucleus where positively-charged protons (with some gluing together help from neutral neutrons) are tasked with reigning them in. Next-door-neighbor atoms join together in strong “covalent bonds” when they share pairs of electrons. This strong gluing is how molecules are formed. But atoms can also interact through weaker attractions that don’t involve electron housing rearrangements, they just involve charge-based attractions.

In a neutral molecule, the # of protons = the # of neutrons. If there’s a “full” imbalance meaning you have more electrons than protons or vice versa, you get a formal charge and we call such charged particles ions. More electrons than protons gives you a negatively-charged ANION & more protons gives you a positively-charged CATION.

The # of protons an element has is fixed – it’s what defines an element (e.g. carbon has 6 and will always have 6 and hydrogen has 1 and will always only have 1 – if it had 2 it’d be helium). But the electrons, especially the more loosely-held outermost ones called valence electrons can roam around a little and even get lured away. They have to get fully lured away to give you a full charge, but they can get lured a little farther away from their “owning” nucleus without leaving when they’re in an unfairly-shared covalent bond. In such “polar covalent bonds,” one atom is electron-hogging (electronegative) and it pulls their shared electrons closer to it, leaving its neighbor partly positive, and making itself partly negative.

finished in comments