Gastroesophageal reflux disease occurs when acidic stomach juice or food flows back from the stomach into the esophagus. A range of factors contribute to the pathogenesis of GERD, including dysfunction of the anti-reflux barrier, disturbances in gastric emptying, abnormal esophageal defense mechanisms, decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone, and dysfunction of the esophagogastric junction15. The present study induced reflux esophagitis in rats using a non-surgical method based on repetitive fasting and overeating. This specific dietary pattern can make mice overeat, leading to alterations in the lower esophageal mucosa that resemble GERD. Most models require surgical intervention to create a reverse acid flow into the esophagus. These surgical models did not reflect normal physiological condition. Additionally, most of the animals quickly perished due to excessive surgical stress12. We expanded the section to integrate recent literature (2022–2023) on GERD, vitamin D, and autonomic dysfunction. Novelty emphasized: our study is the first to combine histology, cytokines, HRV, and vitamin D3 intervention in a physiological non-surgical RE model.

Our research investigated the impact of vitamin D3 supplementation on heart rate variability (HRV) and the healing process in a rat model of esophageal reflux. Recently, new findings highlighted the importance of vitamin D3 for maintaining a healthy digestive system. The occurrence of esophagitis was confirmed by gross, microscopic evaluation and scoring of esophageal tissue. The control of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) pressure is primarily accomplished by the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)16. Vitamin D3 seems to have significant potential for preventing and treating ulcerative disorders by promoting cell growth and specialization. It also can control the release of gastrin through both endocrine and paracrine pathways, which subsequently affects the secretion of stomach acid and pepsinogen by chief cells17. In this experiment, the morphological examination of the esophagus and histological scoring of H&E-stained esophageal sections demonstrated that esophageal inflammation and damage were markedly decreased in vitamin d treated groups. These results suggested that vitamin D3 reduced reflux-related damage. In contrast to our results, Wei et al. revealed that no morphologic and histopathologic changes were observed in vitamin D3 groups compared with the control group in acute RE despite improvement in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines1. Wei et al.’s research used a surgical model for RE, which could account for this apparent discrepancy. Additionally, our non-surgical fasting refeeding paradigm maintains systemic physiology while surgical induction is less physiological, resulting in extra stress and more mortality. Moreover, vitamin D3 was given as a therapy and a preventive strategy in our trial, whereas the study of Wei et al. only used it as a preventative intervention.

The rat models of RE showed significant elevation in several key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-618. IL-6 is produced by vascular endothelial cells, mononuclear phagocytes, and fibroblasts as part of the body’s response to acute phase reactions upon stimulation by IL-1β and TNF-α. Studies showed that esophageal cell suspension had significantly elevated IL-6 in vitro from RE patients19. Increased lipopolysaccharides- toll-like-receptor-4 (LPS-TLR-4) binding triggers interleukin (IL)-18 synthesis, enhancing a series of inflammatory reactions. Six Pro-inflammatory chemokines like as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α are all transcriptionally promoted20. This disrupts the luminal esophageal barrier by retrograde inflammation from the submucosa, as well as potential unfavorable relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and reduced esophageal motility. The result is cytokine cascade spreading, direct acid entry through the mucosal barrier, and further exacerbation of GERD21. The substantial inhibitory effect of vitamin D3 on inflammatory response might be a possible way to improve RE. Thus, the healing potential of vitamin D3 may be attributed to decrease TNF-α and IL-6 as shown in the immunohistochemical and ELISA results. Consistent with our data, previous findings have shown that Vit D3 treatment significantly reduced the pro-inflammatory cytokines levels in RE compared with the control group1. We discuss the dual role of vitamin D3: (i) anti-inflammatory effects via suppression of IL-6 and TNF-α, and (ii) autonomic regulation via improved HRV. Correlations between cytokines and HRV parameters further strengthen the mechanistic link. Preventive supplementation of vitamin D3 significantly inhibits the mucosal damage in our study. This discovery could be connected to vitamin D’s capacity to control the lower esophageal sphincter motility and to prevent the aberrant rise of inflammatory mediators. In line with these results, it was previously reported that vitamin D3 deficiency could dysregulate the function of the lower esophageal sphincter22.

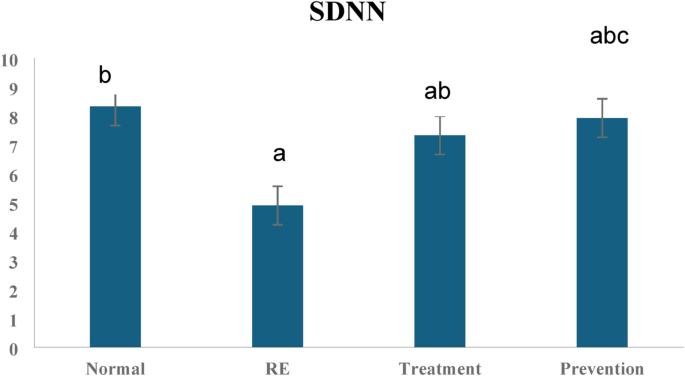

HRV plays a vital role as an indicator of autonomic ANS function and cardiovascular health. Decreased HRV has been linked to a range of health issues, including gastrointestinal conditions like GERD. Recent research indicates that vitamin D3 might impact autonomic regulation and gastrointestinal function. This discussion delves into the potential ways vitamin D3 could influence HRV in a rat model of GERD. Patients with GERD often experience autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and the pathophysiology of GERD is connected to disruptions in autonomic nervous system function23. In the recent study, HRV findings showed that rats in the RE group displayed signs of autonomic dysfunction, as demonstrated by lower SDNN, LF, and HF values, along with a higher LF/HF ratio. The study showed a reduction in HRV’s overall time domain parameters. Since HF is a measure of parasympathetic activity, the decrease in our study suggests a shift in the sympatho-vagal balance towards sympathetic predominance. Our results were following Milovanovic et al., who revealed that patients with GERD showed similar decreases in SDNN, LF and HF; however, HF decreased significantly23.

The stress and frequent arousal linked to GERD can trigger the sympathetic nervous system, reducing HRV24. Additionally, a physiological connection exists between the peripheral nervous system and the inflammatory processes25. According to a meta-analysis conducted by Williams et al., there is a negative correlation between time- and frequency measurements of the HRV and pro-inflammatory markers such as the cytokine IL-626. Evidence suggests that long-term GERD may trigger an immunological reaction that aggravates cardiac dysrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation. The lower esophageal sphincter’s myogenic control may be compromised by decreased vagal activity brought on by the inflammatory response. This could promote lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and, as a result, likely increase the frequency of transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter23.

The alteration in autonomic balance can cause several cardiovascular problems over time, highlighting the need to look into possible treatments that could raise HRV. According to recent research, vitamin D3 insufficiency causes autonomic dysfunction and structural and ionic channel remodeling. It may put a person at risk for fatal cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death27. Vitamin D3 might impact both autonomic regulation and gastrointestinal function. This discussion delves into the potential ways vitamin D3 could influence HRV in a rat model of GERD. The time and frequency domain HRV parameters showed improvement in the vitamin D3-treated groups. Moreover, vitamin D3 administration in the prevention group could prevent changes in the frequency domain HRV parameters. Therefore, vitamin D’s possible contribution to the enhancement of HRV is confirmed. The improvement in HF results strongly suggests the possible effect of vitamin D3 on parasympathetic activity. Following our study, Nahar et al. concluded that vitamin D3 supplementation could improve heart rate variability by increasing the parasympathetic activity in chronic asthmatic patients28. There are few documented investigations on the relationship between vitamin D3 and HRV. However, some studies supported the positive relationship between vitamin D3 levels and HRV parameters in Vitamin D3 deficient conditions29. In contrast, prior investigations comparing vitamin D3 deficient patients with low cardiovascular risk to healthy subjects with adequate vitamin D3 levels didn’t discover significant differences in the time domain HRV measures30.

Very little data explains the link between vitamin D3 and autonomic nerve function. Studies have shown that autonomic neurons rich in vitamin D receptors (VDRs) exist31. The improvement of HRV in our study could be attributed to the ability of vitamin D3 to lower the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF. The hypothesis that IL-6 may have a role in decreasing vagus activity and causing parasympathetic autonomic dysfunction was supported by a prior study. A decrease in vagal activity would likely compromise the cholinergic anti-inflammatory system, thus aggravating the condition32.

The observed association between HRV indices and IL-6 levels implies that vitamin D3 operates both systemically through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and locally at the esophageal mucosa. This is consistent with findings showing that vitamin D receptors are present in autonomic neurons and that vagal activity can directly regulate cytokine release31. Collectively, these results support the existence of neuroimmune pathway through which vitamin D3 exerts protective effects.

Based on previous findings, TNFα may influence the neuronal pathways that regulate the gastro-intestinal system and cause significant inhibition of gastric motility by affecting the brain stem’s vago-vagal reflex circuits. They demonstrated that TNFα activates the sensory elements of this circuit (nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), possibly by presynaptic modulation of the glutamate release from vagal afferents to NTS and sensitizing presynaptic intracellular calcium release. As a result, the efferent elements produce gastro-inhibition by action on the enteric plexus, thus disturbing the entire autonomic gut control33. The innate immune system’s various immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils, are thought to be inhibited by the β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR). Interestingly, low concentrations of noradrenaline NE can raise macrophage TNF levels. However, acetylcholine Ach inhibits TNF release via binding to macrophages’ α-7-nicotinic acetylcholine (Ach) receptors. Thus, in chronic patients, a decrease in parasympathetic tone decreases the activation of α-7-nicotinic Ach receptors, increasing the production of cytokines like TNF and ultimately causing prolonged intestinal inflammation. Enteric neuron synapses mediate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway by releasing Ach at the synaptic junction with macrophages via vagal efferent fibers34.

Immunostaining results revealed increased esophageal TGF- β expression in rats with RE. However, its expression in the prevention and treatment groups was moderate. The cytokine TGF-β is necessary for some cellular processes, including inflammation, fibrosis, and immune system regulation35. It has been proposed that gastric acid exposure into the esophagus in GERD induces tissue remodeling by stimulating TGF β. Additionally, variations in TGF-β expression and signaling mediators may be crucial in the emergence of GERD36. Prior research suggested that TGF- β contributes to the breakdown of the esophageal epithelial barrier by inhibiting the expression claudin-7, a tight junction molecule37. Additionally, sympathetic activity has been demonstrated to increase macrophage TGF-β expression38. This may explain the moderate decrease in its expression after vitamin D3 supplementation. The possible impacts of TGF-β on HRV alteration are still unknown, partly because earlier research produced contradictory results. Wang et al. found a strong relation between TGF-β and the decrease in HRV39. Although Yang et al. found no correlations40. Another recent study confirmed that Increased TGF-β levels would cause a reduction in the HRV41. However, the involved mechanisms aren’t fully understood. Further research is needed. When vitamin D3 is supplemented in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, the bioavailability of TGF-β is considerably reduced42. The inclusion of TGF-β highlights its potential contribution to esophageal remodeling. Vitamin D3’s moderate reduction of TGF-β supports its role in barrier integrity and ANS regulation, consistent with recent findings37,41. This study has limitations. A DMSO-only control group was not included, although solvent volumes were negligible. Only male rats were studied; sex differences warrant future exploration. HRV may be influenced by non-GI systemic factors, though correlations with cytokines strengthen disease relevance. Long-term outcomes beyond 2 months were not assessed.