I (Katelyn) have temporarily escaped to the Amazon jungle, where the internet cannot even reach me. So this week, I left the YLE keys with my team and our good friend—and scientific communication rockstar—Jess Steier. You’re in good hands. Jess, take it away…

Hello YLE readers! I’m Jess Steier, public health scientist and founder of Unbiased Science, stepping in while Katelyn is on a much-deserved vacation. (During brief periods of WiFi connectivity, she’s sending pics that have me very jealous.)

What a week to guest-host: flu season is brutal, the new dietary guidelines are… interesting, the policy landscape is shifting fast, and the annual reader survey needs your feedback. Let’s get into it.

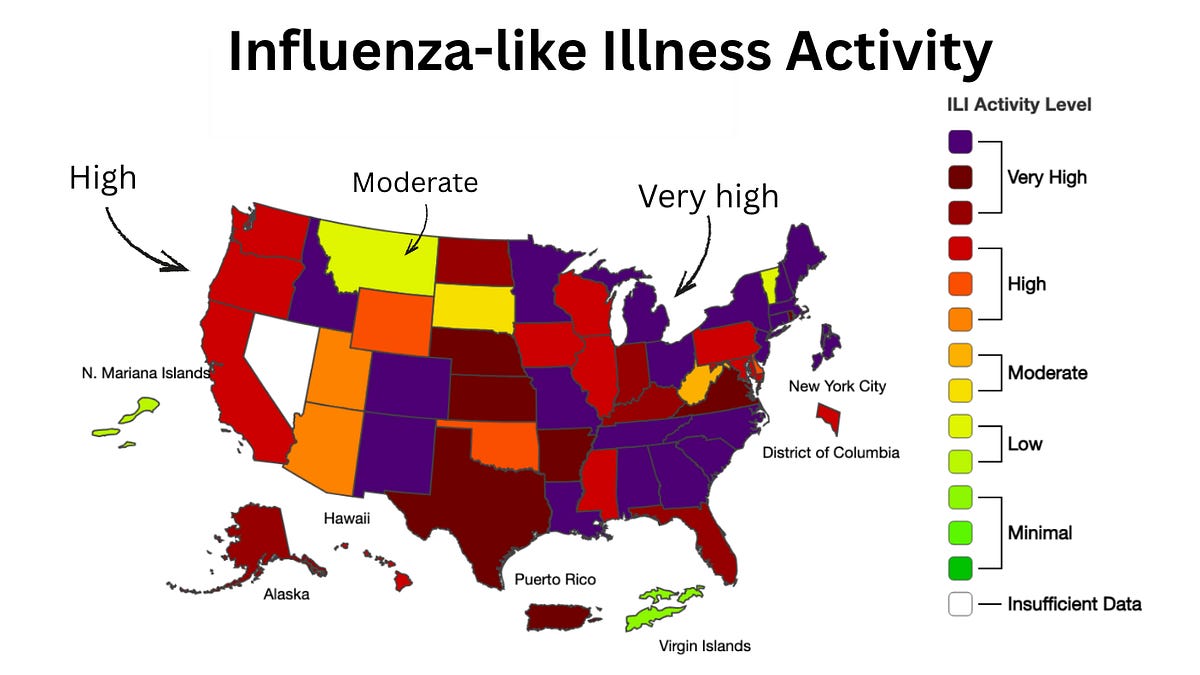

Flu. Buckle up, folks. We’re in the thick of a very rough flu season. The CDC tracks “influenza-like illness” (ILI)—doctor visits for fever, cough, and sore throat—as a proxy for respiratory virus activity. Most of those cases right now are flu. ILI is the highest it has been since 1997-98 (nearly 30 years), and the highest on record since the CDC started tracking. Last season, infections peaked at the beginning of February, and we’re already seeing similar rates a month earlier this year. And infections will continue to increase, since they haven’t peaked yet.

Source: ILINet. Annotations by YLE.

Source: ILINet. Annotations by YLE.

Emergency department visits are highest among kids ages 5-17, with children under 5 close behind. Seventeen children have died from the flu so far this season. For context, last year set the record for pediatric flu deaths (280). Looking at this horrible season, we might see similar rates this year, unless uptake of the flu shot—which greatly reduces the risk of hospitalization and death—catches up.

Subclade K, the latest offshoot of H3N2 (type A)—basically a slightly updated version of the virus we already know—emerged over the summer and is to blame here. It’s better at evading this season’s flu shot and prior immunity. It has accounted for roughly 80% of flu samples tested so far.

What this means for you: The best thing you can do is get a flu shot, and make sure everyone in your family 6 months and older has received one. It’s not too late.

The flu shot might not fully prevent an infection, but it can greatly reduce severity and reduce spread in the community.

Despite changes to the Health and Human Services (HHS) childhood vaccination schedule, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends the flu shot for everyone 6 months and up. (HHS taking the flu shot off the list amidst a flu season that could break records for pediatric deaths is cruelly tone deaf.)

If you do get sick, prescription antivirals like Tamiflu or Xofluza can reduce severity, hospitalization, and even death—especially for high-risk groups. The sooner you start, the better. I’m working on a deep-dive on antivirals for you later this week—stay tuned!

Even if you’ve already gotten the flu, getting a flu shot (if you haven’t yet) can help you. Since there are multiple strains of flu floating around, and the shot protects against some of them well, it can boost your overall immunity.

Other protective measures help, too: wear a mask in crowded indoor spaces, improve ventilation when possible, and stay home if you’re sick.

Measles. The U.S. has confirmed over 2,200 cases and 3 deaths this season—the highest annual total since 1992. Two major outbreaks are driving the surge: South Carolina (313 cases, with 125 added last week alone) has now spread to North Carolina and Ohio, and the Utah-Arizona outbreak continues to grow (nearly 400 cases combined). For latest full Yale School of Public Health SITREP report, go here:

YSPH VMOC Special Report Measles The Americas Jan 11 2026

1.45MB ∙ PDF file

The big question is whether the U.S. will lose its measles elimination status, which we’ve held since 2000. Canada lost theirs in November. If ongoing outbreaks are linked to the Texas outbreak that started last January—meaning continuous transmission for 12 months—we could be next. The Pan-American Health Organization — our regional version of WHO—is set to evaluate U.S. data soon.

Some good news: Covid-19 rates remain low nationwide, and common cold viruses (like rhinoviruses and seasonal coronaviruses) are down. RSV cases are lower than this time last year but starting to rise.

I’ll let Megan, YLE’s registered dietitian nutritionist, take it from here…

Last week, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and HHS released the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The DGA are updated every five years to guide nutrition policy, education, and programming for health professionals. While some federally funded programs like school meals must follow them, others use them as best-practice guidance. As an RDN, I reference the DGA often in my work.

Historically, the DGA has aligned with its Scientific Report—a public, multi-year evidence review by an independent advisory committee. This cycle, the DGA diverged from that report (released in 2024), openly criticized it, and introduced a separate Scientific Foundation developed privately by contracted scientists.

Reactions to the new DGA vary widely, including praise for its emphasis on “real” whole foods, confusion over vague or conflicting messaging, and concerns about its propaganda-like language, questionable scientific rigor, and opacity in the review process and author selection.

Notable takeaways include:

Significant reduction in length (10 pages versus the previous 164) to make it simpler and more accessible, but potentially at the expense of detail, guidance, and nuance that clinicians, schools, and policymakers rely on to translate recommendations into practice.

Continued emphasis on nutrient-dense food groups—fruits, vegetables, whole grains, protein foods, and dairy—with expanded inclusion of full-fat dairy and red meat, more explicit guidance to limit highly processed foods, and stronger limits on added sugars.

A heightened focus on protein, increasing recommended intake by 50–100%, with less emphasis on plant-based sources.

Encouragement of animal fats (e.g., beef, beef tallow, whole milk, butter), while still keeping the saturated fat limits to <10% of calories (~22 grams/day).

Note: This level is nearly reached with a glass of whole milk (4.5 grams), 1 tablespoon of butter (7 grams), and a 4-oz serving of ribeye (9 grams).

Softened alcohol guidance, removing specific daily limits (<1–2 drinks) despite growing evidence that no amount of alcohol is safe, and instead offering only a vague recommendation to consume less for better health.

Explicit removal of health equity as a consideration in reviewing evidence and shaping guidance, including factors like socioeconomic status, race, culture, research representation, and diverse population needs.

Replacement of the MyPlate graphic with an inverted food pyramid.

Source: https://cdn.realfood.gov/DGA.pdf

Source: https://cdn.realfood.gov/DGA.pdf

How will these changes affect daily life for most folks? For many adults, not much. Most Americans don’t follow the guidelines anyway. Still, the DGA shapes guidance for federal nutrition programs, such as school meals and nutrition assistance programs, which serve at least 1 in 4 Americans, and informs recommendations from health professionals. That’s why its clarity and scientific integrity remain important for both individuals and public health.

Would a deeper dive into the new guidelines be useful? If so, what questions do you have for us? Let us know in the comments.

The “Big Beautiful Bill” changed Medicaid eligibility, adding new work and renewal requirements. When they go into effect in January 2027, they will affect care in a myriad of ways, including cancer prevention.

An analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) last week predicted that, due to losing Medicaid coverage, millions of people will lose access to cancer screenings.

Their projections? More than one million missed screenings in the next two years, resulting in 155 preventable deaths. This study focused on implications for breast, colorectal, and lung cancers, all of which have shown increased survivorship after widespread screening implementation. This estimate is conservative; for example, it does not include recommended cervical cancer screening.

There will also be significant variation across states: in states that expanded Medicaid (where a larger fraction of the population is covered), more screenings will be missed.

Bottom line: This is just one direct health impact for those who will lose Medicaid coverage next year.

Will states step in? Probably, but it depends—and probably not to the full extent of the Medicaid coverage net, at least in the short run.

There may be opportunities to expand screening capacity at other points of care, such as community health centers and primary care visits, but this will require investment in already stretched systems.

I unfortunately have had the experience of a super uncomfortable, borderline painful, hastily accomplished Pap smear. I get it: as an important cervical cancer prevention tool, we’ve needed them. But like many of the other women in my life, I dread them.

Enter the at-home human papillomavirus (HPV) self-collection test. We can collect our own samples using at-home kits, and they are now FDA approved as a cancer screening tool in Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) guidelines. The at-home kits are less invasive, involve less equipment, don’t require a trip to the clinic, and are a welcome alternative for people who have experienced sexual trauma.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) first endorsed self-collection swabs for clinical use back in 2024. They were then available through prescription only in May 2025. These updated guidelines reflect additional data that vet how they can be reliably used to test for HPV, the infection that causes the majority of cervical cancers, and expands access without prescriptions.

For context, the HRSA recommends that women aged 30 to 65 at average risk of cervical cancer get screened with HPV testing—now including at-home tests—every five years, and women aged 21 to 29 at average risk get a Pap smear every three years. (The American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines recommend beginning to test for HPV at 25 years.) This at-home test aims to increase screening rates: an estimated 1 in 4 adults are not up to date with cervical cancer screenings.

This brings us to some nuance:

First, there’s a risk of people forgoing a clinician’s care, like at an annual physical, to collect samples at home.

Even though most insurance plans will have to cover them in 2027, they might not be available to everyone—especially people without insurance.

An HPV test is not a Pap smear. Pap smears also check for precancerous cells on the cervix, which might become cancerous if they are not treated properly.

Self-collection is not recommended for everyone. People with the following conditions should talk to their clinician before opting for at-home tests:

Abnormal tests or precancers in the past

Solid organ or stem cell transplant

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Taking medicines that suppress the immune system

Exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) before birth

If you want to try this option:

Find FDA-approved self-collection kits through your doctor’s office, Planned Parenthood, or other clinic.

Talk to your clinician about whether you’re a good candidate for at-home testing, and how to stay on schedule, follow up in case of a positive result, and stay accountable for other appointments.

HRSA notes that clinician-collected samples are still preferred, since an abnormal result can immediately be followed up with additional testing at the clinic.

Minimum wage increased to $15 an hour in 19 states. An economic change on the surface, with real public health gains down the line. Research shows that increasing income improves self-reported health, improves social interactions, reduces overtime work, increases birthweights, and can make life just a bit more affordable, improving mental health and well-being.

You can set resolutions that stick. It’s January, and resolutions are on the brain. According to psychology research, the best type of goals are the ones that are specific and manageable:

Specific means that you can look back on your day or week and know whether you kept your resolution. Resolutions work best when you choose them for you and your “why”—not because of external pressure.

Manageable means it fits into your life. You can connect whatever new habit you’re trying to build to what you already want or need to do, like walking while listening to your favorite podcast. Or think about when you were able to reach your goals in the past to help you recreate those conditions.

That’s it for this week!

Love,

Jess

Jess Steier, PhD, is a public health scientist and founder of Unbiased Science. Megan Maisano, MS, RDN, is a registered dietitian nutritionist. During the day, Megan works at National Dairy Council, a non-profit dairy nutrition research and education organization. (She does not write about the dairy industry for YLE.) Hannah Totte, MPH, is an epidemiologist and YLE Community Manager.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches more than 425,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions.

This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below: