The environment around a tumor often puts a chill on the immune system. Researchers at Peking University and Shenzhen Bay Laboratory have reported that they’ve combined two approaches to heat up immunity against solid tumors. The result is one molecule that can be both a checkpoint degrader and a cancer vaccine (Nature 2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09903-1).

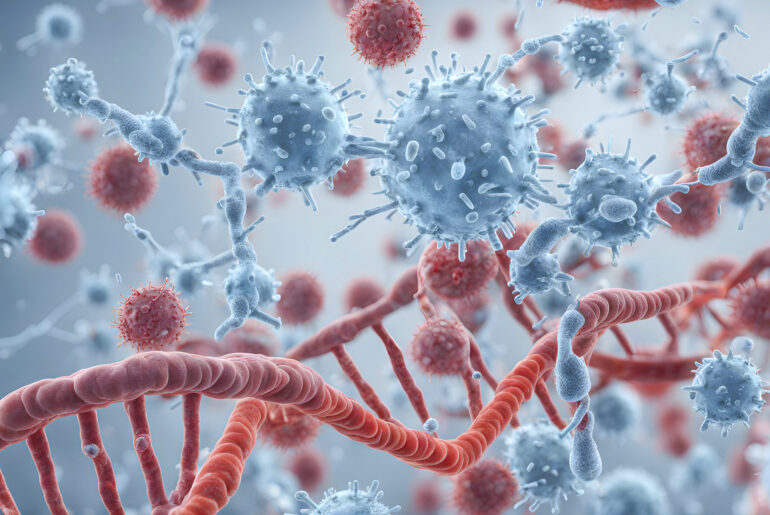

The human immune system has ways to detect unhealthy cells, but cancers develop evasive maneuvers to survive. For example, while normal cells display snippets of internal proteins on their surface, cancer cells turn down this system, hiding their mutations from immune surveillance. Mutant cells also tend to express checkpoint proteins that block immune-cell activity. A variety of immune therapies, including vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors, aim to reactivate the immune system in “cold” tumor environments.

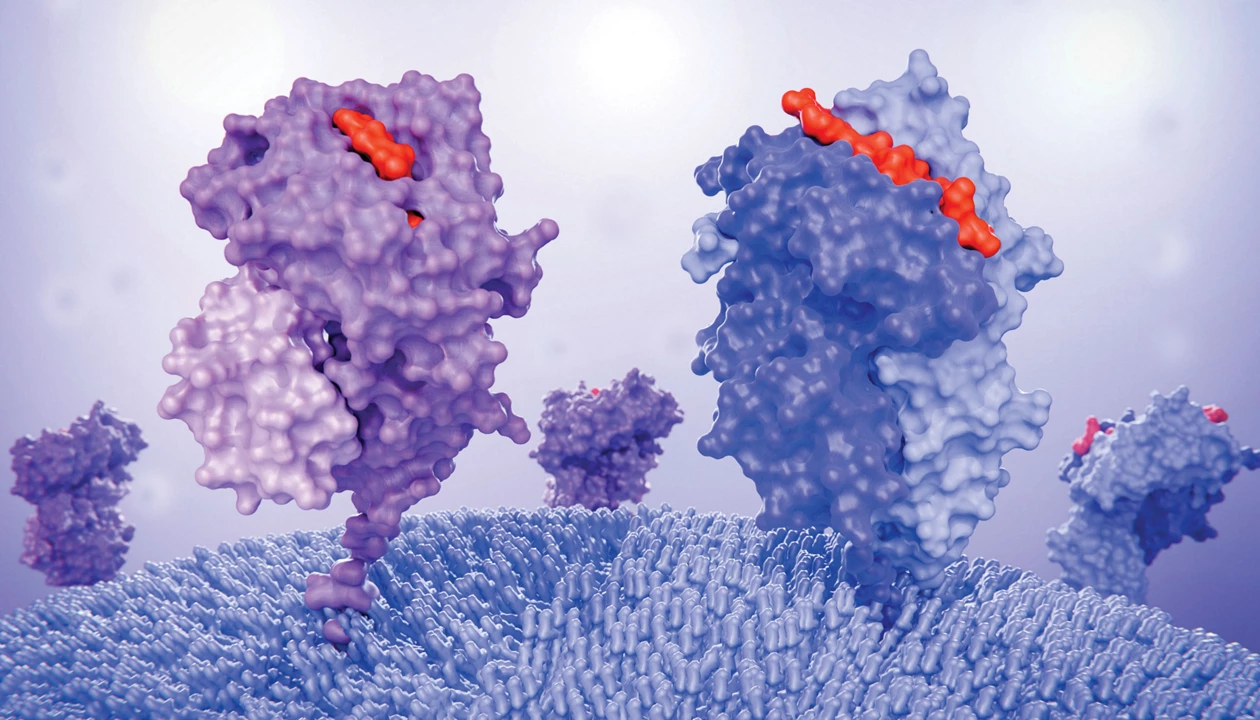

To develop a tumor-fighting treatment, researchers led by Peng Chen engineered a covalent surface degrader molecule targeting the immune checkpoint protein PD-L1. Other teams have developed degraders for PD-L1 and other cell-surface antigens, but here, the authors added a second function. “Instead of just destroying the immune checkpoint protein PD-L1,” they write in an email to C&EN, they asked, “could we leverage its internalization process to deliver a cargo?”

The researchers introduced a peptide cargo, hoping that after destroying PD-L1, treated cancer cells would present the peptide through their surface-display system. They chose a peptide from the common virus cytomegalovirus, reasoning that bystander immune cells around the tumor would already be primed to recognize traces of that virus and would destroy the tumor cells as soon as the PD-L1 brake was removed.

Xin Zhou, a chemical biologist at Harvard University who reviewed the paper, calls the approach “a very creative application of membrane protein degraders” in an email to C&EN.

When testing their design, dubbed iVAC, in cell culture, the researchers discovered that not only did the cargo present on the surface of the cell as hoped, but the molecule also increased the expression of surface-presentation genes, boosting the cells’ overall visibility to the immune system.

In a mouse cancer model and in a cell culture model with a mix of cell types from patients, the researchers found that injecting the degrader into a solid tumor did in fact activate immune cells to attack the tumor.

“They’re able to heat up the tumor,” says Michael Super, a protein engineer at the Hansjörg Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University who focuses on cancer immunity. He praises the approach for its novelty and efficacy, adding that injecting directly into a solid tumor may be a good approach to focus immune activation where it’s needed and avoid the runaway harms of overactivation. He adds that because iVAC is chemical and not genetic, it may reduce the risk of off-target effects that some cancer vaccines carry.

Nicolas Béry, a researcher at Inserm focusing on targeted degraders, similarly finds the degrader-vaccine combination novel. He says it seems versatile; in principle, combination molecules could also target checkpoint proteins besides PD-L1, he says. But “the toxicity of the approach should be carefully deciphered,” because even traditional checkpoint inhibitors like monoclonal antibodies can cause immune reactions against healthy tissue.

The authors tell C&EN that their molecules will need further refinement to be used in the clinic but that they are excited about the proof of concept, adding, “We see iVAC as the beginning of chemical reprogramming of anti-tumor immunity.”

Laurel Oldach is a senior editor and life sciences reporter at C&EN.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2026 American Chemical Society