Last week, United States health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr released the government’s revamped dietary guidelines for 2025 to 2030.

These recommendations on healthy eating are updated every five years and help shape food policy and education for millions of Americans.

Under the slogan “eat real food”, the new guidelines recommend people “prioritise protein at every meal”, eat full-fat dairy and plenty of whole grains, and limit ultra-processed foods. A new food pyramid has also been redesigned and flipped on its head.

But are the guidelines based in good science? And how much has actually changed?

Much of the core guidance is unchanged

As in previous versions, the new guidelines promote nutrient-rich foods – such as fruits, vegetables and whole grains – and appropriate portions.

They continue to recommend people get protein from a variety of sources and limit added sugars and salt. Saturated fat remains capped at less than 10% of total calories.

This is consistent with the long-standing body of nutrition evidence.

Diets rich in whole foods are the most strongly linked to good health overall. There is also evidence they help prevent and manage heart disease, diabetes and – increasingly – mental health.

So, what’s different?

1. More protein

One of the major changes is an increase in recommended protein intake. The previous recommendation was 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight each day – it’s now 1.2–1.6 grams.

The change was based on a rapid review, which mainly focused on weight loss and exercise studies.

However, this evidence base is too narrow to make dietary recommendations for the whole population, which has varying needs.

The revised guidelines also encourage eating protein at every meal, without explicitly prioritising lean options.

2. Full-fat dairy

The guidelines also recommend full-fat rather than low-fat dairy products.

Yet many people – particularly those at higher risk of heart disease – may continue to benefit from choosing reduced-fat dairy. This is the Heart Foundation’s position in both Australia and the US.

3. Limit ultra-processed foods

The new advice explicitly says people should limit and avoid ultra-processed foods.

This is in line with a growing body of research linking them to chronic disease and inflammation.

Previous guidelines recommended eating “nutrient-dense foods” without specifically mentioning ultra-processed foods.

4. A new – inverted – food pyramid

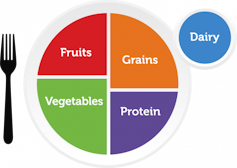

The new “Real Food” website contrasts its food pyramid with the 1992 food pyramid. But that model had already been replaced by MyPlate in 2011.

A plate diagram replaced a previous food pyramid in 2011.

USDA

In this diagram, half the plate is made up of fruits and vegetables. Whole grains and protein each make up a quarter, and dairy is shown separately.

The new pyramid marks a clear shift. Meats, dairy and oils are at the widest edge – which is now at the top – along with vegetables. Fruits, nuts and grains appear in smaller proportions at the pointy tip.

Confusingly, this contradicts the written recommendations, which continue to promote 2–4 daily servings of whole grains and a variety of protein sources from both animal and plant foods.

This visual focus on animal-based foods may encourage people to exceed the (written) recommendations to limit saturated fats at 10% of what you eat overall, and to balance plant and animal-based foods.

The new food pyramid contradicts some of the guidelines’ own written advice.

USDA

5. Vague alcohol guidance

Alcohol limits have appeared in the guidelines since 1980 – these have now been removed. The new advice is to “limit alcoholic beverages” without quantifying what “limit” means.

Warnings about alcohol’s links to cancers, present in guidelines for 25 years, have also been removed. Scientific consensus links alcohol consumption to at least seven types of cancer.

In 2024, the US Surgeon General called for cancer warning labels on alcoholic beverages.

Read more:

Should Australia mandate cancer warnings for alcoholic drinks?

6. Low carbs recommendation

The advice says people with “certain chronic diseases” may benefit from following a lower carbohydrate diet.

While this is supported by evidence – for example, it can help some people manage type 2 diabetes – reducing carbohydrates won’t be safe for everyone (such as children, pregnant women and older adults).

So this advice shouldn’t be seen as a blanket suggestion.

Conflicts of interest

The scientific report accompanying the new guidelines disclosed that several committee members had financial relationships with food industry groups.

Three of nine members received grants or consulting fees from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. One also received support from the National Pork Board.

At least three members were linked to dairy industry organisations, and another was involved in developing a high-protein meal replacement product.

Industry connections are not new. For example, an analysis of the 2020–25 dietary guidelines found 95% of committee members had conflicts of interest with food or pharmaceutical companies.

However, under the Trump administration, the 2025 development process diverged from standard procedures.

The faster review lacked the usual systematic evidence protocols, public comment period and standard safeguards designed to limit individual influence and conflicts.

The missing conversation

“Eat real food” is simple messaging. But for many, it’s not simple in practice.

Perhaps the most striking omission is the guidelines’ lack of attention to socio-economic realities. The report announces a deliberate shift away from “health equity”, which considers how factors like race and income affect access to healthy food.

Access to affordable, healthy food remains limited across the US, especially for people in low-income communities, rural areas, or those working long and unpredictable hours.

People choose food based on whether it’s affordable, accessible and culturally relevant – but the guidelines overlooked these structural drivers.

Instead, they place the responsibility for healthy eating solely on individuals, rather than within the broader food system.

What does this all mean?

No dietary guidelines, however well-designed, can overcome a food system that prioritises profit over public health.

While these recommendations contain some sensible advice about promoting whole foods and avoiding processed foods, they also introduce contradictions and confusion.

People seeking individualised, evidence-based support for their eating should consult a dietitian.