The immune system remains seriously out-of-whack – in an inflammatory state of overactivation and impaired functionality – following the international gold standard for treating people with latent tuberculosis (TB) and HIV, a team at Texas Biomedical Research Institute reports in Nature Communications.

“The good news is that the treatments control the virus and kill most of the TB bacteria,” said Riti Sharan, Ph.D., Assistant Professor at Texas Biomed and co-corresponding author. “The bad news is that the immune system in the lungs does not fully recover.”

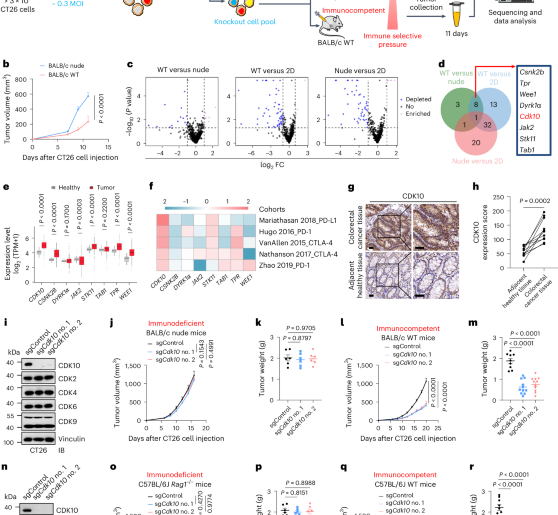

The study is believed to be the most detailed analysis to date documenting what happens in the lungs following the standard treatment for co-infection, which is possible thanks to well-established nonhuman primate models representing humans with latent TB and active HIV.

“We believe this is the first time researchers have shown experimentally how immune responses remain dysfunctional following co-infection and combined treatment,” said Deepak Kaushal, Ph.D., Professor at Texas Biomed and co-corresponding author. “It’s been hypothesized by many, and this is really the first deep dive into it.”

Double trouble

Latent TB is when Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is present but not causing active symptoms of disease and is not infectious. About a quarter of the world’s population – upwards of 2 billion people globally – is estimated to have latent TB. In the U.S., 13 million people are estimated to have the bacteria. The vast majority do not fall ill, but those with compromised immune systems, such as people living with HIV, malnutrition or diabetes, have a higher risk for developing active TB disease. Antiretroviral therapy is highly effective at suppressing HIV, so the virus is no longer the death sentence it once was. Rather, TB has become the leading cause of death for those with co-infection.

Upon a new HIV diagnosis, the World Health Organization recommends antiretroviral therapy to control the virus and an antibacterial protocol called 3HP to help minimize the chance of reactivating latent tuberculosis, which involves taking one pill once a week for 12 weeks.

The Texas Biomed research team has previously shown immune responses remain dysregulated following HIV treatment. This time, they evaluated simultaneous treatment for HIV and latent TB to see if it helped better restore lung immune system functionality.

“Co-infection messes things up for the immune response,” Dr. Kaushal said. “You would think that after treatment the immune responses would reset to normal – that does not happen. That has the potential to explain why co-infected people remain at greater risk for respiratory infections.”

Single-cell deep dive

The team found that specific populations of T cells, which are white blood cells and a key component of the immune system, were imbalanced following treatment compared with the control group. Specifically, following treatment, there were significantly fewer CD4+ effector memory T cells, which are frontline defenders and send early signals to other immune cells to attack. A subset of beneficial T helper cells (TH1) were decreased, while another T cell type (TH17) was increased and may be responsible for continuous immune system activation.

“When the immune system is continuously activated, it leads to immune exhaustion, which increases susceptibility to reinfection with TB bacteria,” Dr. Sharan said.

With the help of single cell RNA sequencing, the team also tracked the activity of macrophages – which are large immune cells that engulf Mtb in the lungs – at the beginning of infection. Macrophage functionality, determined through which genes were turned on or off, changed as early as two weeks after co-infection with SIV, the nonhuman primate equivalent of HIV, and did not change back after completing the treatment regimens.

More therapies needed

Based on these findings, the bottom line is clear.

“We need host-directed therapies,” Dr. Sharan said. “The immune system is not getting any help with these standard treatments. We are controlling the bug, but what about the immune system?”

Host-directed or immunotherapies specifically target a part of the immune system to help improve responses to treatments. The researchers are investigating potential options in their respective labs.

“It’s clear treating TB and HIV is not going to be enough to ensure people are able to go on living healthy lives,” Dr. Kaushal said. “Developing host-directed therapies to restore the immune system could potentially be used not just for TB and HIV, but for a range of respiratory diseases.”

Source:

Texas Biomedical Research Institute

Journal reference:

Sharan, R., Zou, Y., Singh, B. et al. Concurrent TB and HIV therapies control TB reactivation during co-infection but not chronic immune activation. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67188-4