Cancer cells that have broken away from a primary tumor can lurk in the body for years in a dormant state, evading immune defenders and biding their time until conditions are ripe for establishing a new tumor elsewhere in the body, a process known as metastasis.

The vast majority of deaths caused by cancer — as many as 9 in 10 — are caused not by an initial tumor, but by the impact of these metastatic tumors (also known as stage 4 cancer). Understanding this complex process is among the most challenging and urgent needs in cancer science.

Now new research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) shows how metastatic cancer cells prevent the immune system from eliminating them by changing their shape. Scientists at MSK uncovered how cancer cells lower their surface tension, making it harder for patrolling immune cells to latch onto them. The findings, published January 5 in Nature Cancer, illuminate how cancer cells physically adapt to survive.

Dr. Zhenghan Wang

“When cancer cells are round, they have much lower surface tension and it’s harder for the immune cells to attack them and pop them like a balloon,” says senior study author Joan Massagué, PhD, Director of MSK’s Sloan Kettering Institute and a leading expert on cancer metastasis.

The study, led by Zhenghan Wang, PhD, a senior research scientist in the Massagué Lab, was conducted in cells and mouse models of lung cancer.

“Our research suggests that if we can stop cancer cells from entering this soft state, or re-stiffen them, we might help the immune system find and clear dormant metastases before they can seed a new tumor,” Dr. Wang says.

VIDEO | 00:10

Softness protects metastatic cancer cells from immune cells

The ability to change shape helps protect metastatic cells from the immune system. These cancer cells can reorganize their cytoskeleton in response to specific environmental cues, giving them a more relaxed, round shape. When they are round, like the cell on the left, they have much lower surface tension and it’s harder for immune cells to destroy them. The video was recorded by Dr. Zhenghan Wang of the Massagué Lab at MSK’s Molecular Cytology Core Facility.

Dr. Joan Massagué

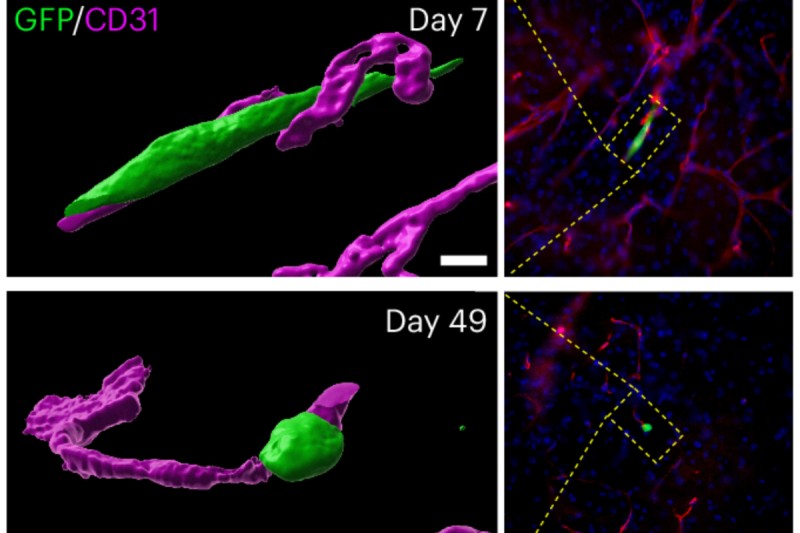

Using an atomic force microscope to study the mechanical properties of cells, MSK researchers were able to observe dormant metastatic lung cancer cells changing their physical shape to help them survive. The cells transition from an elongated and firm spindle shape to one that’s softer and rounder, a bit like letting air out of a balloon — softer balloons are harder to pierce.

This switch from firm to soft is driven by a signal called TGF-beta and the protein gelsolin. Gelsolin helps break down the cell’s internal scaffolding of actin fibers, which reduces the cell’s overall stiffness. Softer, rounder cells are harder for the immune system’s natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells to grab onto, the research showed.

The team also showed how TGF-beta signals change the cancer cells’ shape over time. When lung cancer cells first encounter TGF-beta, they undergo a shift called an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, or EMT for short. The process converts fixed epithelial cells into mobile, invasive mesenchymal cells. As part of this process, the lung cancer cells also become elongated and stiffer.

Significantly longer exposure to TGF-beta, however, causes the cells to ramp up gelsolin production. The increase in gelsolin then breaks apart and reorganizes the cells’ fiber scaffolding, which softens the cell and makes it rounder.

When the researchers blocked TGF-beta, reduced gelsolin, or otherwise prevented cells from becoming soft, however, the dormant cancer cells were more effectively eliminated by immune cells.

In this way, the scientists showed TGF-beta was crucial for helping dormant metastatic cells evade immune defenders over months and years.

By revealing a new mechanism that helps cancer thwart the immune system, the research also points to potential new treatment strategies.

“We hope that with continuing research into dormant metastasis, we can ultimately prevent metastatic cancer by helping the body eliminate its dormant seeds,” Dr. Massagué says.

Additional Authors, Funding, and Disclosures

Additional authors of the study include Yassmin Elbanna, Inês Godet, Siting Gan, Lila Peters, George Lampe, Yanyan Chen, Joao Xavier, and Morgan Huse.

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health / National Cancer Institute (R35-CA252978, P01-CA129243, R01-AI087644, R01-CA266068, T32 CA254875, P30-CA008748), as well as by a grant from the Alan and Sandra Gerry Metastasis and Tumor Ecosystems Center at MSK, a Damon Runyon Quantitative Biology Fellowship, and postdoctoral fellowships from the Alan and Sandra Gerry Metastasis and Tumor Ecosystems Center.

Dr. Massagué owns company stock in Scholar Rock.

Read the paper: “TGFβ induces an atypical EMT to evade immune mechanosurveillance in lung adenocarcinoma dormant metastasis,” Nature Cancer. DOI: 10.1038/s43018-025-01094-y

Dr. Massagué holds the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Foundation Chair.