Artificial stone, also known as engineered stone or quartz, can contain more than 90% crystalline silica. Resins and other chemicals added to the factory-made slabs contribute to making engineered stone dust more dangerous than dust from natural stones such as granite or marble, according to doctors.

Cambria faces 400 lawsuits from stoneworkers for silica-related injuries, most of them in California, Schult said. Other major manufacturers facing lawsuits, such as Israel-based Caesarstone and Cosentino, headquartered in Spain, have developed low or no-crystalline silica alternatives. But Cambria, which owns a quartz mine that supplies its high-silica products, has not.

Maryland Rep. Jamie Raskin said the courts should determine whether manufacturers have any responsibility for the impact of their products on stoneworkers. In one of the two cases against Cambria and other manufacturers that went to trial, the company was found partially liable in a $52.4 million verdict for failing to adequately warn of the hazards. Cambria appealed the jury decision. In a separate case, a jury ruled in favor of the defendant manufacturers, a decision that is also on appeal.

“You are looking for categorical absolute immunity in all of these cases,” Raskin said in a testy exchange with Schult. “On your definition, there’s no defect on the product, right? So how could you ever be held liable?”

Cambria has emerged as a vocal opponent of a doctor’s petition last month asking California to ban cutting and polishing of artificial stone. The Western Occupational and Environmental Medicine Association said such a ban would encourage the use of safer substitutes developed by some manufacturers for the Australian market. That country was the world’s first to prohibit the sale and use of high-silica artificial stone in 2024.

Schult said Cambria’s own fabrication shops have cut artificial stone safely for more than 20 years, without a single silicosis case. A Cambria safety video played at the start of the hearing showed state-of-the-art facilities that use robotic machines to cut slabs in glass-enclosed areas. The company told KQED that Cambria’s fabrication practices include the use of handheld devices, but declined to specify how much of its cutting tasks is done by the robotic machines.

A stone countertop fabricator wears a mask to help protect against airborne particles, which can contribute to silicosis, at a shop on Oct. 31, 2023, in Sun Valley, California. (Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

A stone countertop fabricator wears a mask to help protect against airborne particles, which can contribute to silicosis, at a shop on Oct. 31, 2023, in Sun Valley, California. (Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Some silicosis experts and employers doubt the sophisticated and expensive measures needed to safely handle engineered stone are feasible or affordable for most fabrication shops, which are typically small businesses with fewer than 10 employees.

Cal/OSHA inspectors have found that about 95% of the fabrication operations they’ve visited were not following all of the state’s safety rules. California’s regulations, the nation’s strictest, require artificial stone to be cut or polished with machines that cover the material’s surface in water to suppress dust. Employers must also provide workers with sophisticated respirators that can cost more than $1,000 each, and a ventilation system to clean the air.

James Nevin, an attorney at Brayton Purcell LLP representing hundreds of stonecutters, said that workers are contracting silicosis in even the most sophisticated fabrication facilities.

“This epidemic starts and stops with crystalline silica artificial stone. It is entirely the uniquely toxic product that is the problem, not ‘a few bad actors’ in the countertop fabrication process,” Nevin told KQED in a statement.

Nearly all of the sick stoneworkers in California are Latino men, many of them undocumented immigrants. McClintock, whose district includes parts of California’s Central Valley, said fabrication shops that violate worker protections undercut law-abiding competitors while regulators fail to enforce existing rules.

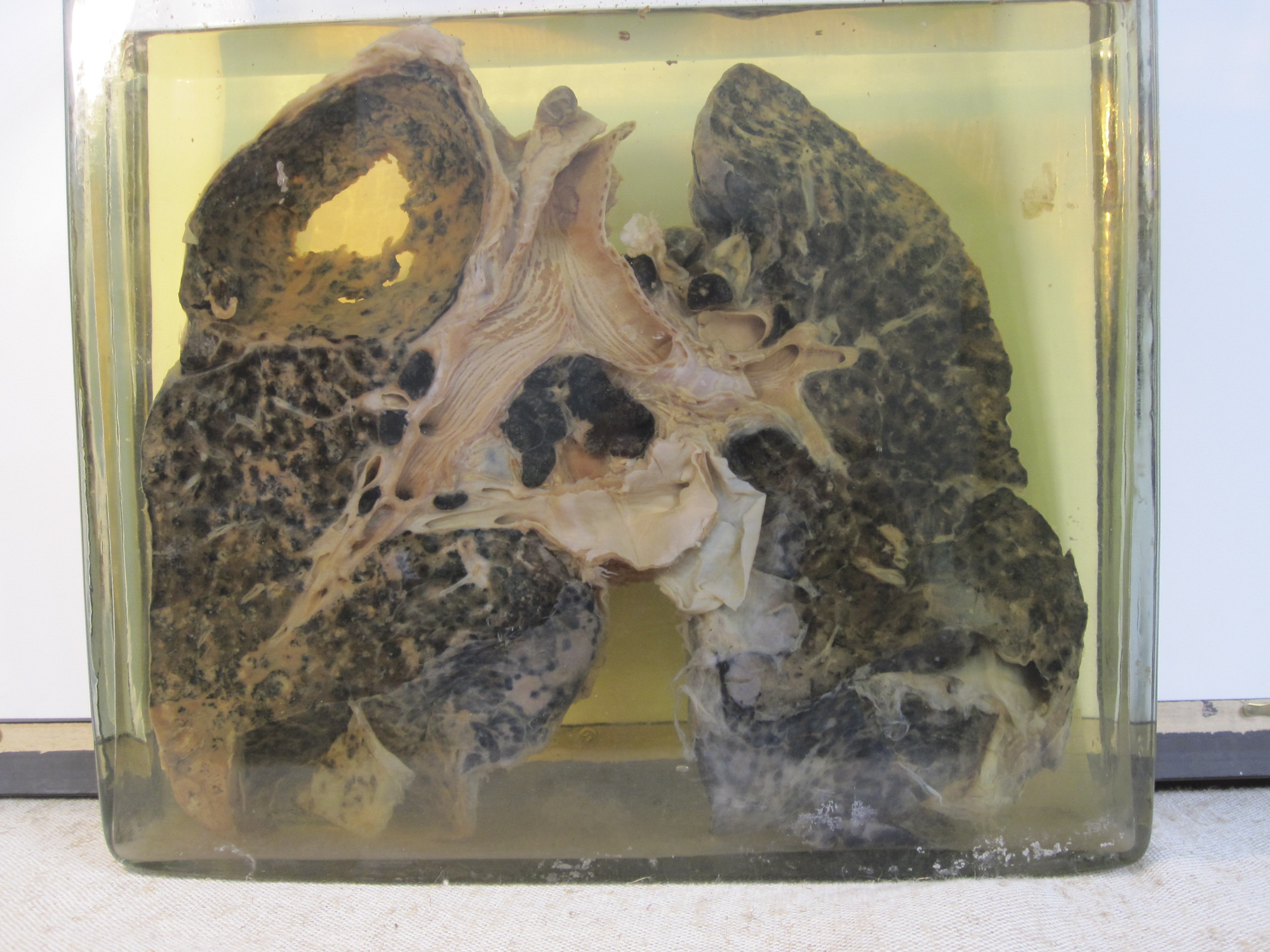

A photo of a pair of lungs with silicosis used in a Cal/OSHA presentation slide about the disease, and rising numbers of cases in California, at a public meeting on Nov. 13, 2025. (Courtesy of Museomed via Wikimedia Commons)

A photo of a pair of lungs with silicosis used in a Cal/OSHA presentation slide about the disease, and rising numbers of cases in California, at a public meeting on Nov. 13, 2025. (Courtesy of Museomed via Wikimedia Commons)

“It appears they’re just turning a blind eye to law-breaking by sweatshops that are breaking our immigration laws, labor, health and safety laws, exposing their employees to the dust that causes silicosis,” McClintock told Schult. “And it appears that instead of enforcing the law against these illegal practices, the Democrats prefer to drive you out of business.”

California is not the only state facing a growing silicosis problem. Dozens of additional cases have been identified in Washington, Utah, Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts and other states where engineered stone is being cut. David Michaels, a former assistant secretary at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, believes thousands more silicosis cases across the country have not been reported.

“Lawsuits play an important role in public health protection. If lawsuits by workers with silicosis are prohibited, these manufacturers will make no effort to prevent more workers from dying or becoming disabled by silicosis,” Michaels, an epidemiologist and professor at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, said.

“We shouldn’t be discussing immunity from litigation. We should be discussing banning this product to make it safe for workers, and that would protect the manufacturers and the distributors as well,” he added. “We should not allow the carnage to continue.”

On Wednesday, fabrication workers not yet diagnosed with silicosis sued Cambria and other major manufacturers and distributors in federal court in San Francisco, seeking to require the companies to pay for medical monitoring for all California workers exposed to artificial stone dust.