Mental fitness is increasingly viewed as a core leadership capability, not a soft skill.

getty

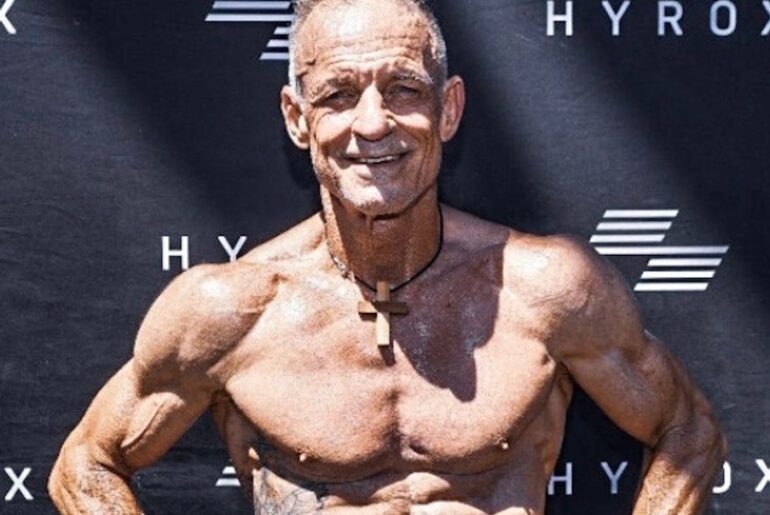

Dr. Gareth Craze has spent his career at the intersection of behavioral science and leadership development. A psychosocial fitness coach, business school professor, and co-founder of Hard Mind Lab, a consultancy specializing in risk management and employee wellness in Australian heavy industry, Craze has coached leaders across industries on everything from workplace performance to executive resilience.

His academic work as a Senior Lecturer in Organizational Behaviour at UEH – International School of Business, combined with his decades of coaching experience, has given him a unique vantage point on what separates leaders who thrive from those who merely survive.

Craze develops this idea further in his forthcoming book, Stronger, Sharper, Smarter, where mental fitness is positioned as a critical but underexamined leadership capability.

Mental health has rightfully become a central focus in professional life, but mental fitness represents something altogether different—and potentially more transformative for how we think about leadership performance today.

The Two-Leader Thought Experiment

Craze often begins his work with leaders using a deceptively simple thought experiment.

“Imagine two leaders with identical experience, judgment, and values,” he says. “One is consistently well-rested, physically active, and properly fueled. The other is chronically tired, under-recovered, and running on caffeine and deadlines.”

The question he poses next reveals an uncomfortable truth: “Faced with a high-stakes decision at the end of a long day, which one would you trust to regulate their emotions, see around blind corners, and make the clearer call?”

Research consistently shows that sleep deprivation significantly impairs cognitive performance, affecting memory, attention, judgment, and decision-making—all critical leadership capacities.

Most people instinctively choose the first leader—even if only by a small margin. That instinct, Craze argues, points to something organizations still struggle to acknowledge: leadership performance is not just cognitive or strategic. It is also, fundamentally, physiological.

“Although any linkage between physical wellness in the body and under-pressure professional performance as a leader might not be a direct one,” Craze says, “most people when confronted with this thought experiment tend to acknowledge that the fed, rested, active doppelganger leader must have some leadership advantage.”

Mental Health Is the Floor. Mental Fitness Is the Advantage.

The distinction Craze draws between mental health and mental fitness is crucial. Mental health, he explains, is ultimately about functioning—being sufficiently free from psychological injury or mental illness to show up and perform one’s job.

“Your mental health or illness is a private matter between yourself, and perhaps your family or physician, and is a matter of respecting your individual rights,” he says.

Mental fitness, by contrast, is about capacity.

“Assuming you are mentally healthy enough to show up and perform your job, then mental fitness is all about how well your mind performs under load, over time, and in conditions of uncertainty,” Craze explains. “Being mentally healthy is a baseline. Being mentally fit is what allows leaders to think clearly at hour ten, stay composed in conflict, and recover quickly after setbacks rather than slowly eroding away,” he says.

Here, the comparison to elite athletics is instructive. In professional sports, no one confuses being injury-free with being competition-ready. Leadership has been slower to make that distinction, even as today’s executives face sustained cognitive and emotional demands that would have been unthinkable a generation ago.

The Physiological Reality of Leadership

One of the most persistent myths in leadership development, according to Craze, is the idea that thinking happens in some abstract cognitive space, detached from the body.

“In reality, every act of judgment, attention and self-control has an underlying physiological component and cost,” he says. “Your brain is a sophisticated physiological system nested within other sophisticated physiological systems, and it draws on sleep, nutrition, movement and recovery to function well.”

Recent neuroscience research demonstrates that physical activity directly enhances executive function, which is the cognitive processes underlying judgment, attention, and decision-making that leaders rely on daily.

This isn’t to say that leaders can’t perform without optimal physical wellness. Craze acknowledges that some leaders emerge and reveal high potential despite being underslept, underfed, and “effectively handcuffed to their office chair. The two-packs-of-cigarettes-a-day centenarian is a real phenomenon.”

But he’s quick to add a statistical caveat: “You and almost all other people are not going to be that kind of running-on-fumes unicorn. More likely, you’ll lose precision. Your error margins will widen. Your emotional reactivity will increase. Subtle bias in your thought processes will creep in quietly.”

When leaders feel overwhelmed, many assume they have a time-management problem—that if only they had more hours in the day, they could accomplish everything without the constant pressure. But this could just as easily reflect the system inefficiencies of an individual mind that has not been properly optimized, suggests Craze. And this is where attending to your mental fitness can be decisive.

Three Domains That Shape Mental Fitness in Leaders

As it relates to leadership, mental fitness tends to show up across three interlocking domains.

Physiological Readiness: “This is the basic foundation,” Craze says. “Stable energy, predictable sleep, and basic physical conditioning determine how much cognitive and emotional bandwidth a given leader has access to on any given day. When this domain is neglected, everything else becomes significantly more difficult.”Cognitive and Emotional Regulation: Mental fitness, according to Craze, sharpens attention and what he calls “decision hygiene.” Leaders with higher cognitive precision (or who are more mentally fit) are better at separating signal from noise, timing important decisions to high-energy windows, and resisting the pull of impulsive action when clarity would benefit from delay. They can feel a full range of emotions without being hijacked by them, responding rather than reacting when the stakes are high, says Craze.Systems for Longevity: Willpower is overrated. Performance improves when systems are designed well: calendars that protect focus, routines that automate recovery, and environments that reduce unnecessary friction. Using what he admits is “a rather hackneyed analogy,” Craze notes that leadership is a marathon, not a sprint—and requires marathon-like conditioning. “Mentally fit leaders are those who design their careers for mind-body durability, not just short-term performance throughput. They align intensity with recovery, performance with connection, and work with life so that their professional wisdom and judgment as a leader improve with experience rather than deteriorate from constant taxation and chronic depletion,” he says.

Perhaps more importantly, Craze emphasizes that none of these domains requires perfection. They just require self-awareness and consistency.

The Cultural Ripple Effect

One of the most compelling insights from Craze’s work is how mental fitness extends beyond individual performance to shape organizational culture.

“Team members very often calibrate themselves and their own behaviours to what their leaders model, especially in pressure-cooker scenarios,” he observes.

The implications are significant.

“A leader who protects their recovery windows gives others permission to do the same,” Craze notes. “[Those] who treat a good night’s sleep as a non-negotiable professional obligation on everyone’s part sends a stronger signal than any breakroom-adorning wellness policy statement ever could.”

In fact, studies confirm that leadership modeling is critical to workplace wellness culture: when leaders prioritize wellbeing through their actions, organizations experience higher retention rates and employees bring their best selves to work.

Over time, these behaviors compound throughout an organization. According to Craze, the benefits are tangible: meetings become more focused and inclusive, HR issues decline, and decision-making improves without requiring additional resources or performance metrics. What begins as one leader’s personal commitment to mental fitness can ultimately transform into broader organizational culture.

A Leadership Responsibility

Craze is careful to distinguish mental fitness from what it is not. “It is not merely performative wellness through modeling good behaviors. It is not about comfort, indulgence, or knowing when to ‘check out’—or even ‘self-care’ in the way many professionals think about that term.”

Instead, he frames it as a matter of professional obligation. “Mental fitness is about collective responsibility. Leaders are entrusted with decisions which affect livelihoods, cultures and a host of long-term, multi-faceted [outcomes]. Taking ownership of the quality of your mind is a massive part of that responsibility.”

As organizations navigate increasing volatility and as artificial intelligence absorbs more routine cognitive work, Craze argues that the truly human leadership edge will lie in qualities like judgment, presence of mind, and adaptive thinking.

While AI handles data processing and automation, leadership increasingly requires the uniquely human capacities that mental fitness supports: creativity, emotional intelligence, ethical judgment, and contextual decision-making.

What’s perhaps most striking about Craze’s approach to mental fitness is that he doesn’t frame it as a cutting-edge trend. “In a way, it’s actually a return to a more basic understanding of both human limitation and human potential, based on a timeless ‘take care of yourself’ wisdom that most of us have (rightly) heard since the cradle.”

The speed of modern life and the chaos of modern business, he suggests, have simply gotten in the way of us taking advantage of basic psychophysiological truths about the intimate connection between our bodies and minds.

The leaders who last, and who lead well, are unlikely to be those who simply push harder. They will be the ones who build the capacity to think clearly, respond wisely, and recover quickly — again and again — over the long arc of a career.