Across Instagram feeds and pet parent WhatsApp groups in urban India, a familiar pattern is unfolding. Influencers post videos breaking down kibble ingredients under alarming titles, such as “What’s really killing your dog.” In these videos, pet owners share screenshots of ingredient labels, circling unfamiliar terms (such as wheat gluten and poultry by-product meal) with red arrows and warning emojis. The conclusion, delivered with absolute certainty, is almost always the same: commercial pet food is poison.

It is a script India has seen before. The same mechanics that turned WhatsApp into a vector for health misinformation (for instance, that gluten causes cancer; microwaves destroy nutrients; and packaged food is toxic) have now found a new target. This time, the anxiety is being projected onto pet owners.

The panic gained momentum during the pandemic. Confined at home, pet owners became hypervigilant. Every minor ailment — a skin rash, digestive upset, low energy — was blamed on kibble. Social media amplified the panic. Anecdotes replaced evidence. A single viral post about a dog’s supposed reaction to commercial food could spark thousands of shares, with each iteration adding layers of unfounded claims. Veterinary consensus got drowned out by the volume of online outrage.

Much of this is driven by the same cognitive bias that fuels health fads in human nutrition: if something is processed, it must be harmful. If an ingredient is a chemical, it must be dangerous. If I don’t eat it, my pet shouldn’t either. The logic is intuitive and emotionally appealing, but largely unsupported by veterinary science.

But companies are sensing an opportunity here, because beneath the manufactured panic lies a genuine shift: urban pet owners, particularly millennials and Gen Z, are willing to spend significantly more on products marketed as “natural,” “clean,” or “human-grade,” regardless of whether those terms have any regulatory meaning.

According to Mordor Intelligence, the Indian pet food market is estimated to have reached about $1.01 billion (around Rs 9,000) by 2025 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 16.7% through 2030

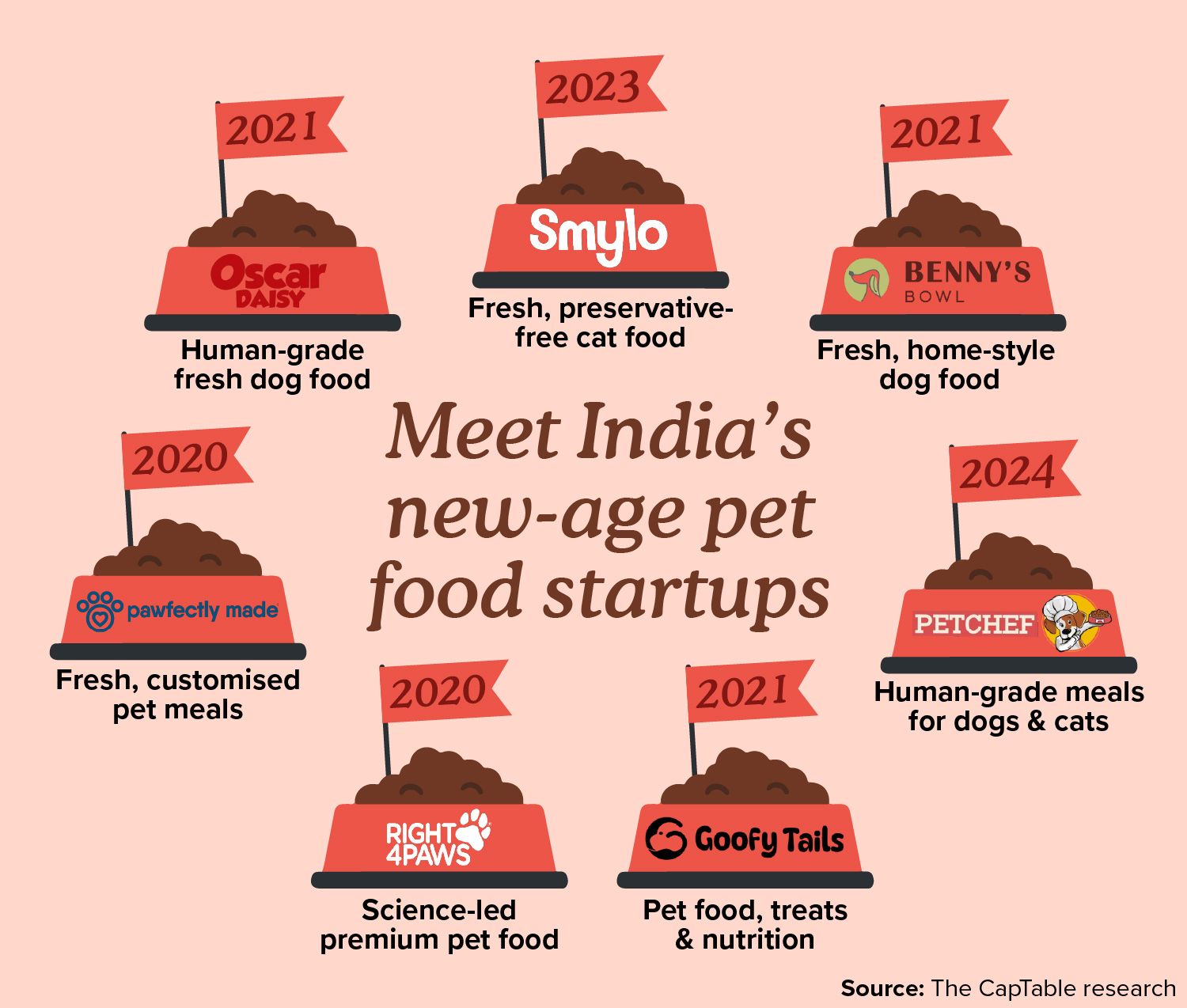

What started as Instagram hysteria has become a commercial opportunity. And brands are moving fast.

The new playbook

The marketing follows a template, but for some founders, it began with something more personal. “We had a cat named Mylo. After a couple of months, we lost him,” recalls Karthikeya Gupta, co-founder of Smylo, a premium cat food brand launched in 2022. “That’s when we started asking ourselves what really went wrong. When we researched deeply, we realised it was really about the food. For pets, especially cats and dogs, what they eat matters far more than anything else.”

The experience led to a business built on specific beliefs about the pet food market. “Many cats in India today face serious health issues,” Gupta says. The company’s perspective is that conventional pet foods could be improved with higher-quality ingredients and better formulations.

Smylo positions itself carefully on credibility. “We don’t launch any product unless we are convinced it has very high credibility for a cat’s health,” says Abhishek Agrawal, who co-founded the company with Gupta. “Pet parents today are willing to pay a 30–50% premium if they believe the product will give their cat a healthier life. People may not have a nutritionist for themselves, but they ask us for nutrition plans for their cats,” he adds.

The capital is flowing in. Venture funds that previously focused on direct-to-consumer fashion or beauty are now evaluating pet food startups. The pitch follows familiar themes: premiumisation, millennial consumers, aspirational spending, and digital-first distribution.

For emerging brands, the market presents both opportunities and challenges. “Big companies can definitely launch similar products and even price them cheaper,” the Agrawal. acknowledges, “but making a genuinely good product at that price is extremely difficult. This category is very transparent. If chicken itself is expensive, you have to ask how cheap cat food is even possible.”

“Our strength is not just the product, it’s how we talk to consumers, how transparent we are, and how we build trust,” Agrawal says. “Today, around 45% of our revenue comes from D2C, and the rest comes from marketplaces. Quick commerce platforms like Zepto and Blinkit are seeing cat food grow faster than dog food.”

It’s a market in transition, with new players making their case to increasingly receptive consumers. But the veterinary community is watching these developments with a more measured perspective.

The science question

Dr Rohini V, a veterinary nutritionist based in Bengaluru, represents a different view of the premium pet food boom. Her practice has given her a front-row seat to changing consumer behaviour and its consequences.

“The premiumisation trend reflects something positive: pet owners care deeply and want the best for their animals,” Dr Rohini says. “That emotional investment is genuine and important. But there’s a gap between marketing language and nutritional science that concerns me professionally.”

Her concern centres around how products are evaluated. “When I assess a pet food, I’m looking at nutritional adequacy, digestibility, feeding trial data, formulation by qualified nutritionists. Many premium brands emphasise ingredients — ‘human-grade chicken,’ ‘no preservatives’ — but ingredients alone don’t tell you if a diet is nutritionally complete or balanced for long-term feeding.”

The regulatory landscape in India adds to the complexity. “We don’t have the same stringent standards that exist in the US or Europe. Terms like ‘natural,’ ‘premium,’ or ‘human-grade’ aren’t regulated here. A brand can use these terms without meeting any specific criteria. For veterinarians, that makes it difficult to evaluate claims,” she adds.

Dr Rohini makes a nuanced point about established brands. “Products from companies like Royal Canin, Hill’s, or Purina are formulated by teams of veterinary nutritionists. They conduct feeding trials, they publish research, they have decades of data. That doesn’t mean they’re perfect or that there’s no room for innovation. But it does mean we have evidence of their safety and nutritional adequacy over time.”

The ‘grain-free’ trend illustrates her concerns. “In markets like the US, grain-free diets have been linked to dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs. The FDA investigated this connection. Yet here, grain-free is marketed as healthier, more ‘natural,’ when the evidence doesn’t necessarily support that. Cats are obligate carnivores, but that doesn’t mean every grain is problematic. It’s more nuanced than the marketing suggests.”

What she observes in her clinic reflects the broader information environment. “I have clients who’ve switched their pets to boutique diets based on social media recommendations. Sometimes there are no issues. Other times, I see nutritional imbalances, calcium-phosphorus ratios that are off, insufficient taurine in cat food, protein levels that aren’t appropriate for the animal’s life stage.”

The fundamental problem, she reckons, is about how we decide what to trust. “In veterinary nutrition, we rely on research, feeding trials, and long-term data. In social media, knowledge comes from anecdotes, testimonials, and influencer recommendations. These are different ways of establishing truth, and they often conflict.”

Her advice to pet owners is pragmatic. “If you want to try premium food, that’s fine. But look beyond the marketing. Ask if the company employs veterinary nutritionists. Ask if they’ve conducted feeding trials. Check if the food meets AAFCO or FEDIAF standards.” AAFCO (the Association of American Feed Control Officials) and FEDIAF (the European Pet Food Industry Federation) are organisations that set nutritional guidelines for pet food in the US and Europe, respectively.

The erosion of professional expertise troubles her, though she understands its roots. “There’s a broader cultural scepticism toward expertise; we see it in human medicine, in science communication generally. Pet owners are bombarded with alarming content about ‘toxic’ ingredients, and they’re scared. I understand that. But fear isn’t the best foundation for decision-making, especially when the decisions affect an animal’s long-term health.”

Still, she recognises the market reality. “Consumer preferences are shifting, and that will drive product innovation. Some of that innovation will be genuinely beneficial. The question is how we separate marketing from meaningful improvement, and how we ensure that pets, who can’t voice their preferences or their discomfort, are protected in the process.”

Where it’s heading

India’s pet food market will continue to grow. But aggregate numbers, such as market sizes, obscure the real story: the premium segment is growing much faster than the overall market. While dog food dominates, with over a 90% marketshare, cat ownership is rising rapidly in urban areas. The pet population in India has grown from 26 million in 2019 to over 40 million in 2024, with dogs accounting for over 36.8 million and cats making up the rest.

The distribution remains remarkably low, which both explains the opportunity and suggests the challenges ahead. Only about 10% of pet owners use packaged pet food, and even among those who do, they use it only 40% of the time. Most Indian pet owners still rely primarily on home-cooked food — rice, dal, chicken, eggs — supplemented occasionally with commercial products.

This creates a dual challenge for the industry. The first is conversion: convincing pet owners to switch from home-cooked to packaged food. The second is premiumisation within the packaged segment: moving those who already buy commercial food from economy brands to premium offerings.

The corporate giants are betting they can achieve both. Their advantage lies not in superior nutrition, with many of their formulations differing only marginally from established brands, but in distribution reach, pricing power, and marketing muscle. A brand like Waggies, backed by Reliance’s retail network, can appear in thousands of neighbourhood stores across tier-2 and tier-3 cities almost overnight, something no startup can replicate.

The premium D2C brands, meanwhile, are banking on a different value proposition: trust, transparency, and community. Their margins are higher, their customer lifetime value is strong, and their brand loyalty is sticky. But they’re limited in scale. A brand selling primarily through its website and quick commerce platforms can capture affluent metros but would struggle to expand beyond them, said a Mumbai based investment banker.

What’s emerging, then, is likely to be a layered market. At the bottom, mass-market brands would be competing on price and distribution. At the top would be premium D2C brands catering to urban, affluent pet parents willing to pay for perceived quality and specialised nutrition. In the middle, there would be a squeeze: mid-tier brands without the distribution strength of the giants or the brand loyalty of the premiums, the banker added.

The regulatory vacuum

But beneath this commercial dynamism lies an uncomfortable truth: India’s pet food market operates in a regulatory grey zone that would be unthinkable in most developed markets.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) does not have a dedicated system for pet food and primarily relies on regulatory standards that are likely to impact the sector only if public health risks, such as zoonotic disease risks, exist.

The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) issued IS 11968:2019 as a specification for pet food, but it remains voluntary. It is worth noting that the FSSAI has made the BIS standards for Compounded Feed for Cattle (IS 2052:2009) mandatory. However, the BIS criteria for pet meals are still voluntary. The implication is stark: animal nutrition in India is only regulated to the extent that it affects the health of human beings.

This has created a situation in which terms like “natural,” “premium,” “human-grade,” and “grain-free” lack a legal definition or enforcement mechanism. A brand can claim anything on its packaging without meeting any specific nutritional or safety standards. For consumers trying to make informed choices, the regulatory vacuum makes it nearly impossible to distinguish between genuinely rigorous brands and those that are essentially marketing operations.

The contrast with international markets is striking. The US’ AAFCO and Europe’s FEDIAF standards require feeding trials, nutritional adequacy statements, and transparent labelling. India has none of this.

Dr Rohini points to this regulatory gap as a core concern. “When I recommend an established brand to a client, I can point to decades of feeding trials, published research, and adherence to international standards. When a new premium brand launches, what do I have to evaluate? Marketing materials and Instagram testimonials. That’s not a basis for making nutritional recommendations that affect an animal’s long-term health.”

The regulatory vacuum also means there’s little oversight of manufacturing practices, quality control, or contamination risks. While major companies maintain their own standards, often aligned with international practices, smaller manufacturers face no mandatory requirements beyond basic food safety regulations that apply to all edible products.

FSSAI is responsible for enforcing safe food, including pet foods, through licensing, surveillance, audits, inspections, and recall management, but without mandatory nutritional standards specific to pet food, enforcement focuses primarily on hygiene and preventing contamination rather than nutritional adequacy.

What’s actually at stake

The Indian pet food market in 2025 sits at an inflection point. Capital is available, consumers are willing to pay premium prices, and brands are proliferating. But the ecosystem lacks the regulatory infrastructure, professional guidance, and evidence base that should underpin decisions affecting animal health.

India has an opportunity to learn from mistakes made in other markets—mistakes that cost animals their lives before anyone realized what was happening.

Consider what happened in the United States from the early 2010s through 2019. Grain-free dog food became the premium segment’s fastest-growing category, with sales in the pet specialty channel growing over 200% between 2012 and 2016. Brands marketed these formulations as “natural,” “ancestral,” and superior to traditional diets. Grains were portrayed as fillers and allergens. Pet owners, wanting the best for their dogs, paid premium prices and made the switch. No one asked whether these new formulations had been adequately tested.

By 2016, veterinary cardiologists began noticing something alarming: an increase in cases of Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM), a serious heart disease where the heart muscle weakens and loses its ability to pump blood effectively. What made these cases unusual was that they were appearing in breeds like Golden Retrievers and Labrador Retrievers, which aren’t genetically predisposed to the condition.

The common thread: most were eating grain-free diets heavy in peas, lentils, chickpeas, and potatoes.

In July 2018, the FDA issued a public alert investigating a potential link between certain grain-free diets and DCM. Between January 2018 and April 2019, the agency received reports of 553 affected dogs. Analysis revealed that over 90% were eating grain-free formulations, and 93% of those diets contained peas or lentils as primary ingredients. Dogs had typically been on these diets for approximately two years before diagnosis. Some showed low taurine levels, an amino acid critical for heart function. Some improved when switched back to traditional diets. Some died before the connection was made.

By November 2022, the FDA had received reports involving 1,382 dogs with DCM potentially linked to diet.

The investigation continues today. Leading theories suggest that legumes may interfere with taurine absorption or synthesis, or that these formulations contain anti-nutritional factors that block nutrient uptake. The exact mechanism remains unclear.

But the damage was already done. Over a thousand dogs were affected. Many died. And this happened despite these products meeting basic nutritional standards on paper—because those standards didn’t require long-term feeding trials.

The irony is devastating: pet owners thought they were making a superior choice. They paid premium prices for what they believed was healthier. Instead, some formulations may have been nutritionally inadequate in ways that only became apparent after years of feeding.

This grain-free-DCM connection illustrates what happens when marketing runs ahead of science. When premium positioning substitutes for rigorous testing. When regulatory frameworks allow products to reach consumers without adequate validation.

India could require feeding trials before new formulations are marketed. It could mandate adherence to international nutritional standards like AAFCO or FEDIAF. It could regulate marketing claims to prevent misleading pet owners.

Instead, the market is developing in a regulatory vacuum, driven by Instagram aesthetics and venture capital, with veterinary expertise sidelined in favor of influencer testimonials.

“My fear,” Dr Rohini says, “is that ten years from now, we’ll look back and realize we created a generation of pets with preventable health problems because we prioritized marketing narratives over nutritional science. And the pets, who couldn’t speak for themselves, paid the price.”