A multidisciplinary team of University of Cincinnati Cancer Center researchers has received a $40,000 Ride Cincinnati grant to study a delayed release preparation, or wafer, of an immunostimulatory molecule to stimulate the central nervous system (CNS) immune system after surgery to remove glioblastoma, a form of primary brain cancer.

Jonathan Forbes, MD, the project’s principal investigator, explained glioblastomas are the most common type of primary cancer of the brain. Only 5% to 7% of patients with a glioblastoma survive five years after diagnosis.

Effective treatments for these tumors have been hard to identify for decades due to two primary challenges:

– The blood brain barrier that usually protects the brain from harmful bacteria also prevents high-molecular weight agent medications from reaching tumor cells.

– The CNS is associated with a “cold” immune microenvironment, making it harder to stimulate an immune response to kill cancer cells that infiltrate the normal brain and are not able to be removed with surgery.

Currently, neurosurgeons can use wafers that release either radiation or general cell-killing agents, but Forbes said these treatments are nonspecific, expensive and not found to provide much benefit to improve patient outcomes.

“After surgery to remove the tumor, we have unencumbered access to a resection cavity that we know microscopically is invaded by tumor cells,” said Forbes, associate professor and residency program director in the Department of Neurosurgery in UC’s College of Medicine and a UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute neurosurgeon. “Why not use this access to enhance the central nervous system‘s ability to clear residual tumor cells?”

Medical student Beatrice Zucca explained the first step of the project was to determine what immune-stimulating molecule was safe and powerful enough to activate the brain’s immune system. The team landed on a protein called Interleukin-15 (IL-15).

“IL-15 is exceptionally effective at activating immune populations that are critical for recognizing and killing cancer cells,” said Zucca, who worked as a neurooncology research fellow under Forbes’ mentorship last fall. “It improves their survival, expands their numbers and enhances their cell-killing function, making it an ideal candidate for driving a coordinated immune attack against a highly-resistant cancer like glioblastoma.”

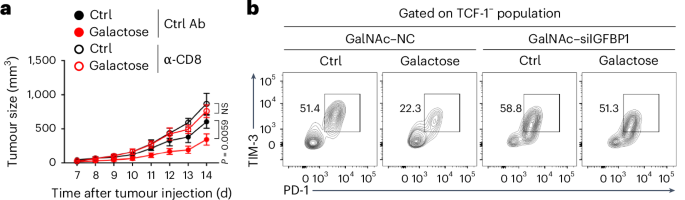

The grant funding will allow the team to test how the immunostimulatory preparation actually stimulates the immune system using glioblastoma-on-a-chip technology developed in partnership with Ricardo Barrile, PhD.

“An organ-on-a-chip is a miniaturized model of a living organ engineered to incorporate the minimal biological elements needed to recreate specific disease conditions,” said Barrile, assistant professor of biomedical engineering in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science. “Instead of testing drugs on flat plastic dishes or relying solely on animal models – which often fail to predict human results due to genetic disparities – we use 3D bioprinting and microfluidics to build a living model of a human organ.”

Barrile’s lab was the first-ever to build a model that integrates human brain cells with glioblastoma cells via a combination of 3D printing and bioprinting. The glioblastoma-on-a-chip model also includes a bioprinted “blood vessel” channel to mimic how drugs move from the bloodstream to the brain and a channel to replicate the immune system.

“This provides a ‘human-relevant’ platform to test therapies safely and accurately before they reach a patient,” Barrile said. “Integrating the immune system was the missing piece and is the key to capture the natural composition of glioblastoma, which in a patient is typically made up to 30% of immune cells. These cells are typically lost during in vitro cell culture.”

While this phase of the project will focus on how the wafer affects the immune response to glioblastoma cells, it could also help move toward the validation of Barrile’s glioblastoma-on-a-chip as a personalized medicine tool.

“We are building a platform that could eventually predict a specific patient’s response to immunotherapy. By using a patient’s own cells on our chip, we can identify the best therapeutic approach for that specific individual before treatment even begins,” Barrile said. “We are essentially moving from a one-size-fits-all approach to a tailored-to-you strategy.”

Forbes noted that in addition to this research, the UC Brain Tumor Center is also researching an approach to overcome the limitations of the blood-brain barrier through navigated focused ultrasound that is able to transiently open the barrier.

“It’s very exciting that we’re actually working on both fronts at the University of Cincinnati, trying to find better treatments for glioblastoma,” Forbes said.

Zucca said the multidisciplinary research has been deeply meaningful, both scientifically and personally.

“It brings together molecular immunology, biomedical engineering and clinical neurooncology in a way that has profoundly influenced my development as a researcher,” Zucca said. “Most importantly, it represents a tangible step toward therapies that leverage the patient’s own immune system to combat one of the most aggressive cancers known.”

Other collaborators on the project include Kevin Haworth and David Plas.