A therapy injected directly into tumors has converted the immune cells already living there into active cancer-targeting cells inside the body.

The finding reframes tumors from passive targets into sites where immune cell therapies can be built in place, rather than manufactured elsewhere.

Inside solid tumors, resident immune cells absorbed the therapeutic payload and began producing proteins that allowed them to recognize and attack cancer cells.

Researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) demonstrated this conversion in tumors.

Professor Ji-Ho Park and his team documented immune cells that shifted from suppressed bystanders into active killers.

The effect unfolded within the tumor itself, where immune cells that normally stall under cancer pressure instead sustained a focused attack over time.

Because the transformation occurred locally, the result set clear boundaries around where the approach can work and pointed toward the delivery challenges that follow.

Tumors block treatments

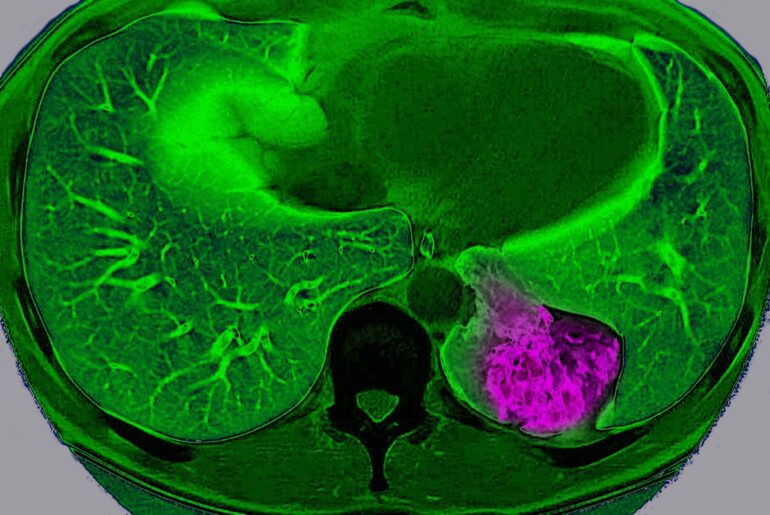

Solid tumors in the lung, liver, or stomach often trap immune cells at the edges, where cancer still grows.

Dense tissue, high pressure, and tangled support fibers restrict movement, so even potent immune drugs struggle to spread.

One review reported that only 1-2% of CAR-T cells, T cells engineered to target cancer, reached tumor cores.

Those physical and chemical barriers help explain why many immune therapies look promising in blood cancers but fade in solid masses.

Immune cells dominate tumors

Many tumors fill up with macrophages, roaming immune cells that swallow debris and signal for reinforcements, sometimes nearing half the tumor mass.

Inside a tumor, cancer can pressure these cells to calm inflammation, which blunts the engulfing response that could remove cancer cells.

When macrophages stop attacking, they may even help tumors grow by shaping blood supply and suppressing other immune cells.

Reprogramming that local workforce matters, because it turns a built-in weakness of solid tumors into a possible advantage.

Teaching immune recognition

The treatment gave tumor immune cells a way to distinguish cancer cells from healthy tissue.

After absorbing the injected drug, macrophages inside tumors began producing a new surface protein that marked cancer cells for destruction.

The instructions came from a temporary genetic message carried by the drug, guiding the cells without permanently altering them.

Because these immune cells already move freely through solid tumors, the approach avoided the access barriers that limit many existing immune therapies.

Delivering genetic messages

Getting mRNA into the right cells required lipid nanoparticles, tiny fat-based capsules that protect fragile genetic payloads.

The coating helped cells take in the package, then release mRNA where cell machinery could read it and build proteins.

By injecting directly into tumors, the researchers pushed more of the dose toward macrophages already present in that tissue.

That local delivery reduced the need for complex cell manufacturing, but it also tied the approach to tumors doctors can reach.

Triggering immune response

The treatment also carried a built-in signal that told immune cells something was wrong and demanded an active response.

Once that signal switched on, macrophages released chemical cues that pulled in other immune cells and kept their attention fixed on the tumor.

That added push mattered because tumors normally suppress these warning signals, allowing cancer to grow even when immune cells are present.

Amplifying immune alarms inside a tumor can also trigger side effects such as swelling or pain, which means careful control will be essential in future trials.

What mouse studies showed

In mouse melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer that can spread fast, the injections slowed tumor growth.

The converted macrophages attacked cancer cells directly and stirred nearby immune cells, so more immune cells gathered at the site.

In some mice, the immune response reached tumors that never received injection, showing effects beyond the treated site.

Because mice and humans respond differently, the results set the stage for careful safety testing rather than immediate clinical use.

Faster immune therapy

Cell therapies often take weeks because labs must collect cells, modify them, and expand them before infusion.

The 2025 paper in volume 19 issue 48 described a shortcut, by programming macrophages in place and letting tumors do the work.

“This study presents a new concept of immune cell therapy that generates anticancer immune cells directly inside the patient’s body,” said Professor Park.

Risks before human trials

Even local immune rewriting can backfire, because engineered macrophages might react to the wrong target and damage healthy cells.

Selecting the target matters, since tumors share some surface markers with normal tissue, especially in organs like the liver.

The approach also relies on mRNA, so the engineered receptor should fade with time, yet dosing schedules remain uncertain.

Researchers will need larger animal studies and careful early human trials to learn where this improves on CAR-T limits.

Turning tumor macrophages into engineered fighters and boosting local alarms could make cell therapy more practical against stubborn solid cancers.

Now the field needs trials that test safety, durability, and antigen choice, plus studies that compare injection sites across cancers.

The study is published in the journal ACS Nano.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–