Photo by Disney

You wonder how it’s all going to come together. There are two FBI agents (Evan Peters and Rebecca Hall) – he’s audibly American, she belongs to that presumably small stratum of the FBI who speak like they went to Roedean. They’re colleagues, they’re sleeping together, they’re pretending it’s “casual”, and they’re investigating a spate of increasingly strange cases.

In this satire of beauty standards and 21st-century narcissism, overseen by the body-horror auteur Ryan Murphy, very attractive people keep freaking out and attacking those around them before spontaneously combusting; a supermodel played by Bella Hadid is among the first to suddenly turn violent and die. But, from Paris to Venice to the Condé Nast offices, the FBI duo are on the case, speaking schoolboy French and Italian whenever necessary. And they soon discover, through photographic records, that while all the victim-assailants are really good looking, two years earlier, they really weren’t.

And then, in much less glamorous Indianapolis, there’s Jeremy. He’s overweight, and has had a tough time with girls. So he spends his time and money on marijuana, camgirls and painful-sounding penis-enlargement pumps, living in (you guessed it) his mother’s basement. Sick of this state of affairs, he engages the services of a grotesque looksmaxxing – the incel-turned-Gen Z term for maximising one’s physical attractiveness – plastic surgeon straight out of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. The surgeon has bad news (“You are an incel, Jeremy”), but he has good news (“I can make you a Chad”), and he promises to fix Jeremy’s self-confidence, apparently by warping his face to hell and giving him a chin like Gaston in Beauty and the Beast.

But when this doesn’t have the desired results, Jeremy returns and shoots up the clinic. His rampage is halted by the prospect of another treatment, which involves a sexual liaison with a beautiful but sinister woman in a dingy, red-lit hotel room. After that’s all done and dusted, the treatment begins, a disgusting convulsion that sees Jeremy ripping out his own teeth and hoisting his guts out of his own throat, while his bones crack and reassemble beneath the skin. Though, as one character says, “Beauty is pain.” After this brutal eclosion, he emerges, as luck would have it, with the looks of a gorgeous, chiselled, up-and-coming actor.

New year, new read. Save 40% off an annual subscription this January.

Bringing our plotlines together is “the Beauty”, an experimental treatment that takes the form of a sexually transmitted infection, and which has escaped confinement. It’s the reason behind the exploding pin-ups, and Jeremy’s got it too. As the narrative spirals (this is the sort of show that takes its premise and sprints with it) we get clues that “the Beauty” is the work of a yacht-dwelling evil billionaire (Ashton Kutcher), who has enlisted an eye-patched contract killer to eliminate everyone now carrying the virus and contain the outbreak.

There’s talk here and there of Ozempic, and the scriptwriters – led and marshalled by Murphy – are quite keen on the dramatic irony of having characters talk blithely about their beauty treatments (boob jobs, thread lifts) soon before they are infected. Otherwise, the series is played as a twisted, violent thriller, with occasional diversions into Houellebecqian sexual politics thrown into the mouths of its characters at odd moments. “I think everything that we do, from the minute we hit puberty, to the second we die, is about sex,” muses Evan Peters’ FBI agent. And the eye-patched assassin offers: “The world is cruel to people who aren’t beautiful. To normal people.”

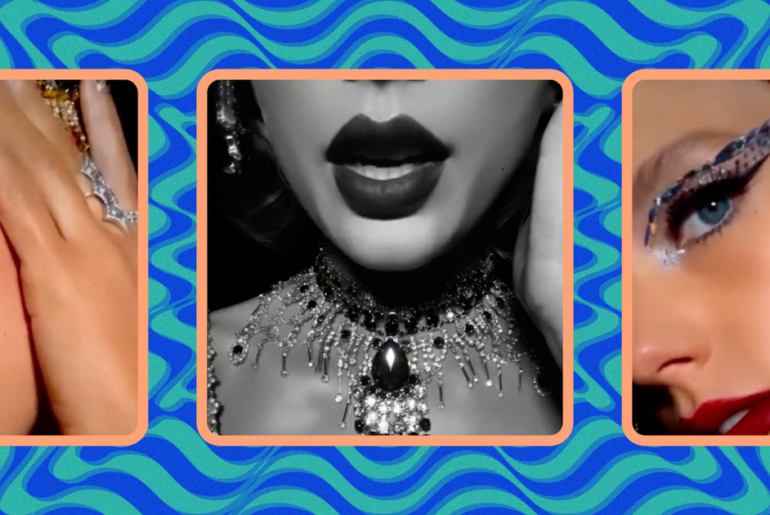

At the risk of impugning Murphy, when you think about it, the very premise of the programme could only have occurred to someone who’s spent a lot of time staring resentfully and imaginatively at better-looking people. But the whole show looks so good – ironically, very conventionally cinematically beautiful – that it feels pointless to linger or ponder. The choreographed fisticuffs, the vast, opulent hotel suites and everything shot in light and shade, by turns flattering and grotesque – this is face-lift TV, taut and tight and very smooth, even if you never really believe it’s real.

[Further reading: Julian Barnes departs on his own terms]

Content from our partners