Published February 10, 2026 09:18AM

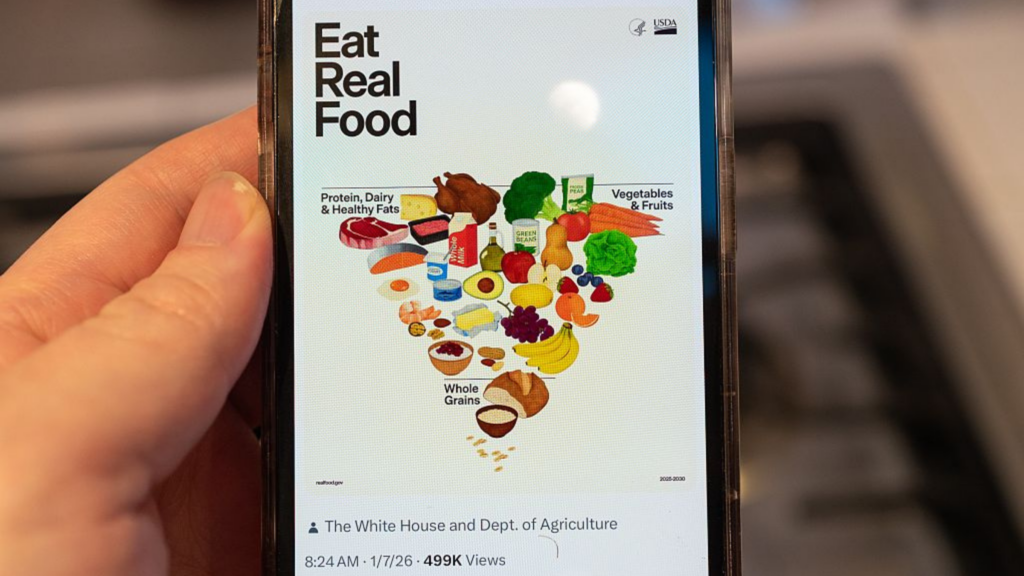

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans—updated every five years by law—serve as the nation’s blueprint for healthy eating. By now, you’ve probably seen the newly released and much‑debated MAHA‑influenced version of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).

This latest edition turns the classic food pyramid upside down and rearranges its priorities: protein‑dense foods now sit at the top while carbohydrate‑rich grains are pushed to the bottom. The streamlined guidelines raise protein targets, discourage heavily processed foods, and offer mixed messages when it comes to dietary fat.

If you’re a runner, you might be wondering what this inverted pyramid means for your grocery cart. Should pasta really lose ground to steak? As a registered dietician, I have some thoughts. I spoke with a sports dietitian, and together we broke down the pros and cons of these controversial recommendations with athletes in mind.

(Photo: Courtesy of USDA)

(Photo: Courtesy of USDA)

The Good

An Emphasis on Whole Foods

This time, the focus shifts toward eating mostly whole foods and getting back to the basics—think real strawberries instead of berry‑flavored Cheerios. There’s no shortage of reasons for runners and other athletes to build their diets around whole foods. As sports dietitian and former professional triathlete Kim Schwabenbauer of Fuel Your Passion explains, “Whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, provide a complex array of nutrients that support training adaptations, recovery, gut health, and long-term performance.”

Few would dispute that one of the strongest elements of these recommendations is the call to cut back on highly processed foods—those ultra‑processed products loaded with refined carbs, added sugars, excess sodium, and various additives. Following that guidance alone could go a long way toward actually making America healthy again.

Still, Schwabenbauer points out that endurance training places unique metabolic demands on the body, and there is a smart, intentional place for processed carbohydrates. During long or intense workouts, rapidly digestible fuel—like gels, chews, sports drinks, or even a bowl of white pasta after a grueling run—can be exactly what an athlete needs. “A whole‑foods‑based diet paired with targeted sports nutrition is often the most effective approach,” she explains.

Animal proteins are prioritized in the new dietary guidelines.

Animal proteins are prioritized in the new dietary guidelines.

Protein Positive

At the top of the inverted pyramid sit the heavy hitters of the protein world—foods like steak, chicken, and salmon. Their prime placement reflects a renewed emphasis on boosting daily protein intake. Current recommendations now land at 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight, roughly double the previous DGA guidance and, frankly, far more aligned with what most endurance athletes actually need.

“A growing body of evidence supports higher protein intakes for physically active individuals, including endurance athletes,” Schwabenbauer explains. “Higher protein intake can help support muscle maintenance, recovery, injury risk reduction, metabolic health, and satiety—particularly during periods of high training volume or energy deficit.”

In practical terms, runners stand to gain by making protein-rich foods—think chicken, fish, tofu, and similar options—a consistent part of their meals and snacks.

Celebrating Fruits, Veggies, Dairy, and Some Sodium

At the top of the pyramid, with the protein heavyweights, are vegetables and fruits. That is to be celebrated. “Increasing fruit and vegetable intake is a priority for runners and the general population alike,” Schwabenbauer says. “These foods provide essential vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, fiber, hydration, and complex carbohydrates that support performance, recovery, immune function, and bone health.”

Consider the three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruit the DGA suggests to be the minimum a runner needs. As a dietician, I appreciated that the DGA calls out frozen, dried, and canned as being good options—choices that can be convenient, budget-friendly, and, yes, nutritious.

The latest DGA continues to encourage dairy consumption—three servings a day—with a particular nod toward full‑fat options like cheese and whole milk, as long as they’re free of added sugars. In other words, maybe skip the fat‑free blueberry yogurt.

“Dairy products provide high‑quality protein, calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12—nutrients that are particularly valuable for runners,” Schwabenbauer says. She notes that for athletes with higher energy needs, full‑fat dairy can be an efficient way to meet both calorie and nutrient demands, as long as saturated fat stays within recommended limits (under 10% of total calories). And the fat in dairy may also help keep hunger in check. This is a win for anyone who’s never been thrilled about skim milk.

The guidelines point out that “highly active individuals may benefit from increased sodium intake to offset sweat losses.” Most sports dietitians, including Schwabenbauer, would agree, especially if endurance activities are lasting longer than one hour and in hot or humid conditions. So the general recommendation of consuming less than 2300 milligrams per day of sodium may not apply to many runners.

The Concerning

Where Are the Carbs?  Carbs are not always the enemy—especially for runners.

Carbs are not always the enemy—especially for runners.

With protein taking center stage and grains pushed lower on the pyramid, Schwabenbauer warns that runners may fall short of their elevated carbohydrate needs if they follow the DGA too rigidly.

“If runners consistently overemphasize protein or fat at the expense of carbohydrates, recovery and performance can suffer,” she says. “Carbohydrates are the primary fuel source for endurance exercise, and runners should actively prioritize them in their diets.”

Research shows many runners already under-consume carbs, with amateurs—who often lack sports‑nutrition guidance—being especially prone to inadequate intake.

The guidelines call for 2–4 servings of whole grains per day, with adjustments based on energy expenditure. For runners, that means intentionally adding more carb‑dense foods—like pasta, bread, and oatmeal—during heavy training blocks. Carbohydrate needs are highly individualized and depend on training duration, intensity, and type, and it’s nearly impossible to meet those needs through fruits and vegetables alone.

It’s also well established that most Americans fall short on fiber, and prioritizing whole grains can help close that gap. Still, there’s room in a runner’s diet for both high‑fiber, complex carbohydrates and low‑fiber, refined options. Because fiber slows digestion, it can trigger GI distress if eaten too close to or during exercise. Outside that training window, Schwabenbauer encourages runners to emphasize fiber‑rich, nutrient‑dense carbohydrate sources—fruits, vegetables, whole grains—to support overall health.

No Love for Plant Proteins

The new DGA isn’t exactly consistent with Michael Pollan’s mantra: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” The heavy emphasis on animal-based protein over plant-based options doesn’t quite align with current research on diet and long‑term health. One global analysis of 101 countries, for example, found that populations consuming more plant‑derived proteins—think chickpeas, tofu, peas—tend to have longer adult life expectancies. “I was surprised not to see more emphasis on plant-based options such as lentils, legumes, tofu, tempeh, and edamame in the visual representation of the guidelines,” Schwabenbauer says. You practically have to squint to spot a plant-based protein in that pyramid.

Her broader message, though, is reassuring: Both plant‑ and animal‑based proteins can fit into a well‑rounded diet for runners and can fully support their protein needs.

Boozey Recommendations

The updated guidelines take a noticeably softer approach to alcohol, offering the vague suggestion to “consume less alcohol for better overall health.” But for someone already drinking heavily, that advice lands about as effectively as telling an overtrained runner to “just ease up a bit.” In reality, athletes—and really anyone—stand to benefit from keeping alcohol intake to a bare minimum.

“Research consistently shows that alcohol can negatively affect athletic performance and recovery by impairing motor skills, hydration status, aerobic performance, and muscle protein synthesis—even when protein intake is adequate,” explains Schwabenbauer. She adds that long‑term, higher alcohol use is linked to poorer body‑composition management, nutrient deficiencies, weakened immune function, and a greater risk of injury.

The silver lining is that today’s non‑alcoholic beers are genuinely worth raising a glass to.

The Confusing

Despite what some headlines might suggest, the new DGA doesn’t give anyone a green light to load up on saturated fat. Sorry, carnivores. Historically, the guidelines have advised keeping saturated fat to about 6–10% of total calories, and the latest version still caps it at no more than 10%.

The confusing part is that many of the foods highlighted in the recommendations—steak, cheese, whole milk, butter, beef tallow—make it extremely difficult to stay under that limit. They’re also calorie‑dense, which complicates energy balance since fat contains twice the calories of protein or carbohydrate.

The guidelines add that “significantly limiting highly processed foods will help meet this goal,” but swapping processed seed oils for butter or beef tallow isn’t exactly a strategy for reducing saturated fat intake. There remains strong scientific evidence that lowering saturated fat and replacing some of it with polyunsaturated fats—like those in fatty fish, nuts, and seeds—can meaningfully reduce heart‑disease risk.

The DGA also advises choosing fats that provide essential fatty acids and cites olive oil as an example. That’s where the fact‑checking gets shaky. “While olive oil is an excellent source of monounsaturated fat and has well‑documented cardiovascular benefits, it is not a significant source of essential fatty acids,” Schwabenbauer notes. “Essential fatty acids—omega‑6 and omega‑3—are found primarily in polyunsaturated fat sources, including many seed oils, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish.”