A groundbreaking study carried out in Israel and Ethiopia, and released on Thursday, sheds light on how bacteria in the gut can actively boost the immune defenses in people living with early stages of HIV.

The research, led by a husband-wife team, Prof. Eran Elinav of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot and Prof. Hila Elinav, head of the Hadassah AIDS Center in Jerusalem, shows that the microorganisms living in the digestive tract, known as the gut microbiome, make up an active organ in the body’s immune system.

The report, published despite severe setbacks, was published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Microbiology. One of the study’s first authors was forced to flee his home in Ethiopia when civil war broke out while he was conducting research there, and the lead researcher’s lab at Weizmann was destroyed by an Iranian ballistic missile attack on the institute this past June.

The report’s findings pave the way for new medical therapies that target the body’s bacterial ecosystem to bolster immune systems in people living with HIV.

“Our study provides strong evidence in humans that the microbiome and the immune system causally affect one another,” Eran Elinav said. “In fact, the microbiome acts as a kind of an immune organ — it both shapes and responds to immunity.”

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

From left to right, Dr. Lorenz Adlung, Dr. Melina Heinemann, Dr. Rafael Valdés-Mas, Dr. Stavros Bashiardes, and Dr. Jemal Ali Mahdi, who took part in an international study about the connection between the gut microbiome and HIV. (Courtesy)

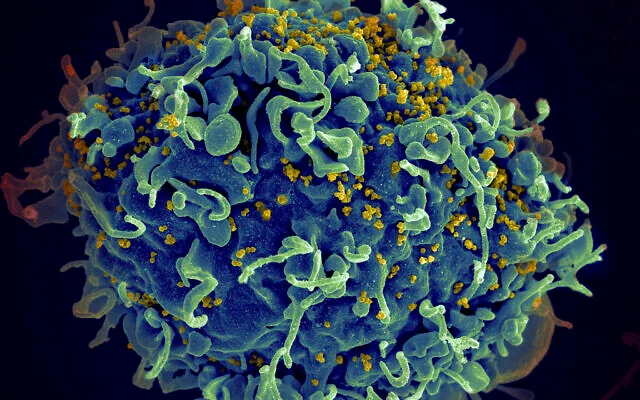

HIV targets the body’s immune system

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks and weakens the body’s immune system. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) occurs at the most advanced stage of infection.

HIV targets white blood cells, which makes the patient more vulnerable to diseases such as tuberculosis, infections, and some cancers.

HIV is transmitted between humans when infected bodily fluids enter another person’s bloodstream, most commonly through unprotected intercourse, the sharing of used syringes, or from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding.

However, with proper treatment, not everyone with HIV will develop AIDS.

Schoolgirls pose with placards as they align in a formation of the red ribbon to raise awareness on ‘World AIDS Day,’ in Amritsar, India, on December 1, 2025. (Narinder NANU / AFP)

According to the Health Ministry’s most recent figures, there are 9,064 people in Israel living with HIV. In Ethiopia, about 600,000 live with the virus. The latest World Health Organization figures show that more than 40 million people around the world have HIV.

Analyzing the microbiome

The gut microbiome is a vast ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, that live within the intestines.

These essential microbes direct the immune system to distinguish between harmless substances and dangerous pathogens. When this delicate balance is disrupted, it can trigger chronic inflammation and leave the body vulnerable and weak.

For their study, the Weizmann researchers analyzed the composition of the gut microbiome in the stool of about 70 people living with HIV in Israel and a similar number in Ethiopia, collecting samples from each at several time points over the course of the viral infection.

A picture taken through a car window shows Ethiopian Amhara militia fighters, who fight alongside federal and regional forces against the northern region of Tigray, as they mobilize towards Tigray, in the northwest of the city of Gondar, Ethiopia, on November 9, 2020. (EDUARDO SOTERAS / AFP)

When the project began, Dr. Jemal Ali Mahdi, one of the study’s key members, was pursuing a PhD at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He joined Eran Elinav’s lab at Weizmann as a visiting student.

Mahdi became one of the study’s first five co-authors, together with Drs. Stavros Bashiardes, Melina Heinemann, Lorenz Adlung, and Rafael Valdés-Mas, and was responsible for collecting the samples in Ethiopia, together with the local medical team.

However, shortly after he returned home, civil war flared up in the region, and he was forced to escape to the United States. He later returned to Ethiopia to help complete the study, despite the ongoing danger.

For the research, the scientists compared the microbiomes of participants in both countries to those of uninfected people from the same geographical area. All HIV-positive participants received the standard antiviral therapy available in their country, although in Ethiopia, the drugs tended to be less advanced than those available in Israel.

A 3D illustrative image of rod-shaped bacteria and cocci in the human microbiome (Dr_Microbe; iStock by Getty Images)

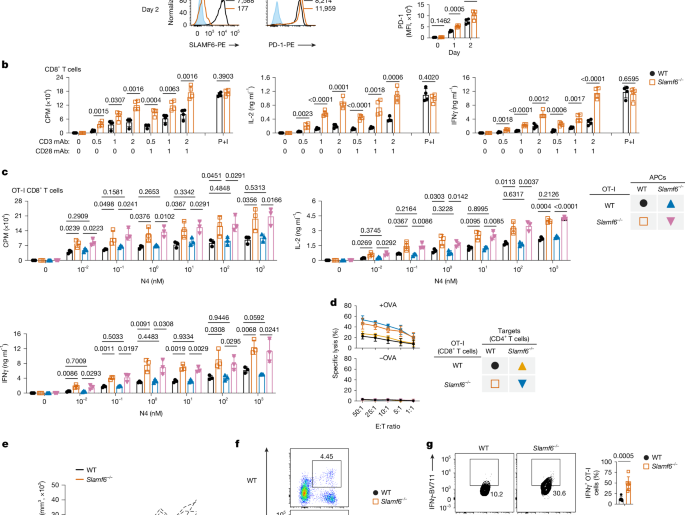

In addition to profiling the microbiome, the scientists measured levels of CD4 T cells, a vital immune cell that coordinates the body’s defense against infections.

In people with HIV, the virus gradually destroys the CD4 T cells, and, if left untreated, the CD4 count eventually plunges, opening the door to more serious illnesses associated with AIDS.

Much of the destruction of these cells occurs in the inner lining of the gut, which serves as a major hideout for HIV.

“The gut serves as a kind of reservoir for HIV, and T cells in its lining remain damaged even when the immune system in the rest of the body recovers as a result of antiviral therapy,” Hila said.

The microbiomes of people living with HIV were different from those of the uninfected control group. Moreover, the scientists noted that the mix of gut microbes continued to change with the progression of HIV.

Some of these microbial shifts appeared in both Ethiopian and Israeli participants, suggesting universal biological rules; others were unique to one country, probably reflecting the impact of local diet and lifestyle on the resident gut microbes, the researchers said.

“We believe the virus is not affecting the bacteria directly,” Eran said. Instead, the scientists found that HIV affects the immune system, which normally secretes “natural antibiotic molecules.”

Illustrative: This electron microscope image made available by the US National Institutes of Health shows a human T cell, in blue, under attack by HIV, in yellow, the virus that causes AIDS. (Seth Pincus, Elizabeth Fischer, Austin Athman/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH via AP)

The scientists then conducted a further test and transferred gut microbes from people living with HIV and from uninfected volunteers into mice that either had no microbes at all or whose microbiome had been greatly reduced by antibiotics.

Since mice are not susceptible to HIV, any immune changes in the animals could not be caused by the virus.

At first, the results stumped the researchers, they said.

Microbiomes from HIV carriers raised the levels of CD4 T cells in the mouse intestines even higher than in mice that received gut microbes from uninfected donors.

This demonstrated the primary role of the microbiome in shaping immune function during HIV infection, the scientists said.

However, in some of the participants who had progressed to severe immune deficiency and AIDS, their microbiomes no longer provided support to the immune system. Mice that received gut bacteria from these AIDS patients had low CD4 levels, and the “helping hand” of the microbiome was gone.

Critical for places without advanced antiviral treatment

The scientists said that future treatments for HIV patients might involve targeting the microbiome through a nutritionally balanced diet, probiotics, or even bacteriophages — bacteria-eating viruses.

“Much work remains to identify the exact microbes and molecules involved,” Hila said. “But our study suggests that, in the future, altering the microbiome might help support immunity and lower the risk of life-threatening infections in people living with HIV.”

Hila, who volunteered in a clinic in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region, which has been troubled by poverty and ongoing civil wars, said that this treatment is “especially critical in places where advanced antiviral therapies are still out of reach, or in patients whose immune systems are not sufficiently restored by antiviral treatment.”