image:

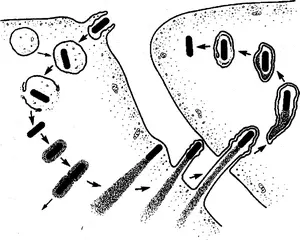

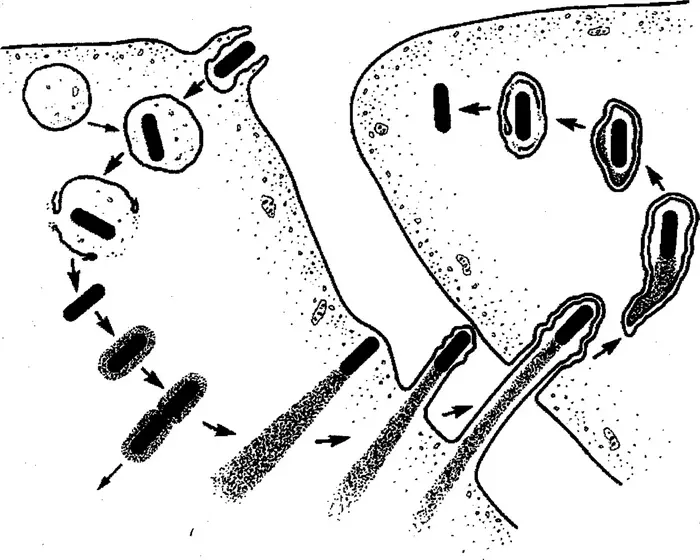

The Listeria lifecycle after it infects a mammalian host. Counterclockwise from upper left, the bacteria are quickly ingested by an immune system cell called a macrophage, where they end up in an organ called the phagosome for digestion. But they escape the phagosome and enlist a protein called actin to build a needle-like protrusion and push it through the cell wall into a neighboring cell, starting the cycle over again. The Listeria strain used for cancer therapy is unable to co-opt actin and thus cannot infect other cells to cause illness.

Credit: Creative Commons License 3.0, courtesy of the American Society for Cell Biology

After nearly 40 years of research on how Listeria bacteria manipulate our cells and battle our immune system to cause listeriosis, Daniel Portnoy and his colleagues have discovered a way to turn the bacteria into a potent booster of the immune system — and a potential weapon against cancer.

Three years ago, Portnoy cofounded a startup, Laguna Biotherapeutics, that worked with scientists in his University of California, Berkeley lab to eliminate the bacteria’s ability to cause disease while retaining its ability to rev up production of a type of immune system cell associated with increased survival in cancer patients. These so-called gamma delta T cells are general-purpose killers of cancer cells or any cell infected by a pathogen — bacteria, virus or fungus.

Laguna Bio will soon ask the FDA for clearance to evaluate the therapy in children with leukemia who have received unmatched bone marrow transplants. Stanford University Medical Center doctors hope that the engineered Listeria will boost gamma delta T cells in pediatric patients and help them stave off graft-versus-host disease, fight potentially deadly infections that take advantage of a transplant patient’s compromised immune system and prevent the cancer from returning.

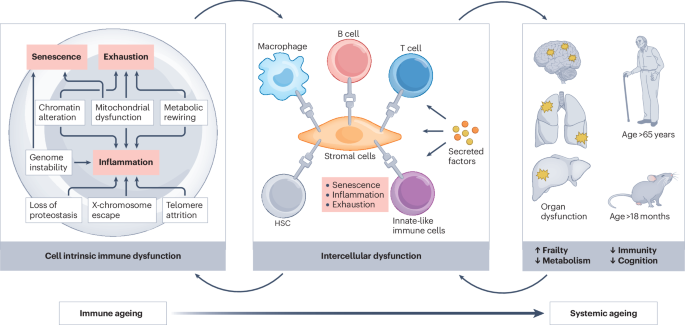

Portnoy and his colleagues foresee a broader application of this Listeria therapy, which is unique among cancer therapies in stimulating the body’s innate immune system to eliminate essentially any cell that puts out a distress signal indicating it’s been compromised. Today’s immunotherapies for cancer typically activate the “adaptive” immune system, boosting cells that recognize and kill cancer cells.

“The issue is that tumors are a suppressive environment, and so the immune system isn’t really even working,” said Portnoy, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and of plant and microbial biology. “There are lots of attempts to try to reawaken the immune system, such as using checkpoint inhibitors, which were originally developed at UC Berkeley. The idea is somewhat similar with Listeria: Listeria itself is seen as foreign and induces an innate immune response, which allows the body to overcome the suppression.”

Late last year, Portnoy and his Berkeley and Laguna Bio collaborators published details of the successful use of the attenuated Listeria therapy in mice in the journal mBio, a publication of the American Society for Microbiology. In another study posted last year on the BioRxiv preprint server, they reported that Listeria can also be engineered to boost another type of innate immune cell — mucosal-associated invariant T cell, or MAIT— that helps defend against infections and possibly cancer.

“What we’re doing is based on decades of literature, chief among them Dr. Portnoy’s work, showing that Listeria generates a really unique immune response,” said Laguna Bio CEO Jonathan Kotula. “We believe that if you want to generate a comprehensive immune response, you need to carefully orchestrate the entire immune system. And attenuated Listeria seems to be doing that.”

Escape from the phagosome

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen that causes gastrointestinal disease and fever in some people but occasionally spreads from the intestines to cause deadly sepsis or meningitis. Researchers have documented how, after infection, the bacteria are engulfed by scavenger cells called phagocytes, where they are captured by an organelle called a phagosome that digests invaders. But Portnoy showed nearly 40 years ago that before that can happen, the bacteria escape the phagosome and set up shop in the cell interior, hiding out from the host’s immune system until they reproduce and spread to infect new cells.

Even though Listeria can hide from the immune system, it does trigger the adaptive immune system to make so-called cytotoxic T cells, or CD8 T cells, which can kill Listeria-infected cells. In the 2000s, Portnoy teamed up with a company called Aduro Biotech to develop a cancer treatment using Listeria engineered to express cancer antigens designed to induce the adaptive immune system to also target a specific tumor.

He first had to construct a version of Listeria that would not make people sick, which he did by deleting two genes required for the bacteria to exit a cell and spread. The bacteria normally do this by hijacking host cell actin, a protein from the cell’s cytoskeleton, and using it to construct finger-like protrusions, which are internalized by neighboring cells.

“We found that a strain that was unable to nucleate actin will still get into the cytosol of cells, still grow and induce a potent immune response, but since it doesn’t spread, it’s a thousandfold less virulent,” Portnoy said.

Aduro combined this strain — dubbed LADD, for Listeria attenuated double deleted — with a cancer antigen and used it to treat nearly 1,000 patients with pancreatic cancer and mesothelioma. But the therapy — essentially a vaccine against cancer — didn’t work as well in humans as it did in mice, in part because humans failed to mount a robust cytotoxic T cell response like mice. Aduro eventually halted the trials and merged with another company in 2020.

An observation by his colleagues at Aduro got Portnoy thinking about using Listeria as a general immune system booster. They observed that in people, Listeria not only induced cytotoxic T cells but also other T cells of the innate immune system, which can target other pathogens, not just Listeria. After the disappointing results with LADD therapy, he decided to pursue this new approach.

The Laguna Bio therapy is an improvement on LADD in that two additional genes have been deleted to make it even safer in humans. Dubbed QUAIL, for quadruple attenuated intracellular Listeria, the strain lacks two enzymes — discovered by Portnoy and former graduate student Rafael Rivera Lugo — required to synthesize essential nutrient cofactors derived from riboflavin, or vitamin B2. These co-factors, known as FMN and FAD, are readily available inside cells, making the bacteria’s own enzymes unnecessary. But the cofactors are not available outside the cell, so the quadruple attenuated Listeria cannot grow extracellularly. In essence, Portnoy converted Listeria from a pathogen that can grow both inside and outside of cells to one that is restricted to the intracellular environment.

“We said, ‘Oh my gosh, this strain fits the criteria that we were looking for’ — a mutant of Listeria that could grow inside of cells but not outside of cells,” Portnoy said. “We have a strain that can’t grow in blood, it can’t grow in the intestine, it doesn’t grow in the gallbladder — these are all extracellular sites for growth — but it grows inside of cells. So that’s the new safer strain, QUAIL. We’re very excited about that.”

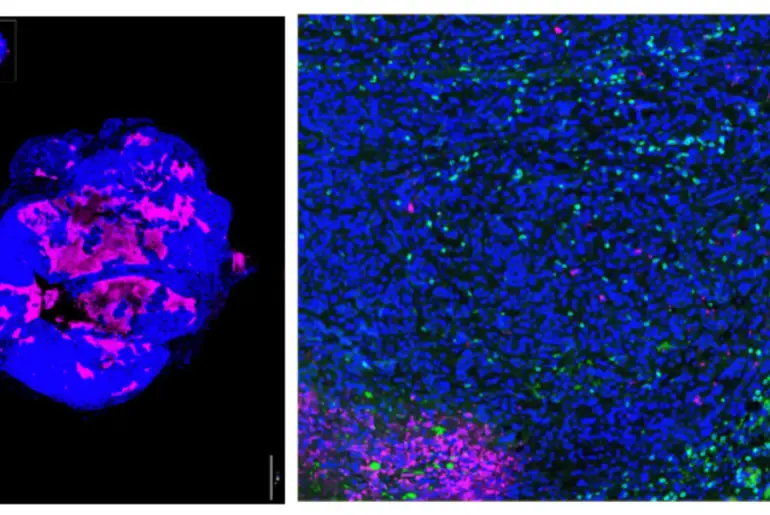

The newly published study establishes the therapy’s safety in mice and confirms that QUAIL retains a potency equivalent to LADD. Because of its inability to grow outside of cells, QUAIL, unlike LADD, cannot grow on the ports and implants often used to treat cancer patients.

One thing that the Aduro human trials showed is that LADD, while not producing much of a boost in cytotoxic T cells of the adaptive immune system, did induce gamma delta T cells of the innate immune system. Since those Aduro trials, gamma delta T cells have been shown to attack and kill cancer cells themselves, as well as produce cytokines that rev up a number of general-purpose immune cells, like macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, to fight infection and cancer. QUAIL could potentially rev up those gamma delta T cells in patients.

“Taking all that body of data that existed before from Aduro allowed us to go forward with this plan that I think is really unique in that it’s informed by robust human data,” Kotula said.

In initial trials in pediatric leukemia patients, Laguna Bio plans to use QUAIL directly to elicit a gamma delta T cell response. The idea is that the T cells will fight infection, rejection and recurrence by directly killing leukemic cells in a patient where the T cells of the adaptive immune system have been suppressed to prevent rejection of the transplant.

Should QUAIL prove safe and effective in the Stanford trials, Kotula envisions treatments for other diseases — multiple myeloma, lymphomas, neuroblastoma, sarcomas and various solid tumors — that have been shown to respond to increased gamma delta T cells. The therapy might also work prophylactically as a vaccine against diseases like malaria, tuberculosis and latent viral infections caused by intracellular pathogens.

“Let’s reinvigorate the immune system, initially focusing on cancers where just that reinvigoration — the gamma delta T cells — has shown promise of efficacy against disease,” Kotula said. “Then, once you have that reinvigoration, it’s always helpful to direct it somewhere.

“I think this can be a part of a broad array of therapies and a piece of a treatment regimen that fits well within how a lot of immune therapies are being administered today. It really works well and complements a lot of the immunotherapy drugs that are already approved.”

The work was supported by Laguna Bio and the National Institutes of Health. The co-first authors of the mBio paper are graduate students Victoria Chevée and Rafael Rivera-Lugo and postdoctoral fellow Mariya Lobanovska. Other co-authors are Leslie Güereca, Ying Feng, Jesse Garcia Castillo and Andrea Anaya-Sanchez of UC Berkeley, Austin Huckins and Jonathan Hardy of Michigan State University, and Edward Lemmens, Chris Rae, Russell Carrington and Kotula of Laguna Biotherapeutics.

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Publication Date

31-Dec-2025