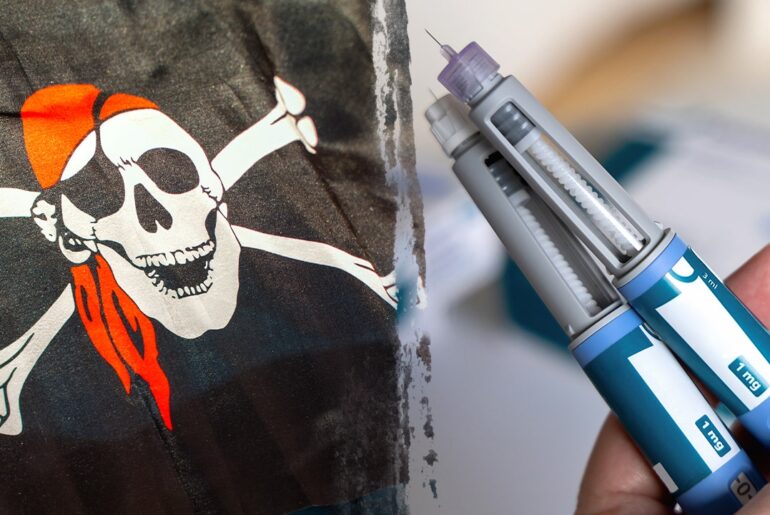

Scientific consensus regarding human health often appears fragile, as staple food groups cycle between being hailed as superfoods or dismissed as significant dietary risks. Such perceived instability reflects a profound structural deficit in high-fidelity data acquisition rather than actual scientific indecision. Currently, the global nutrition science research community lacks the consistent, high-quality data streams necessary to link specific dietary patterns directly to long-term health outcomes.

Known as the nutrition science data drought, this systemic information gap creates ripple effects that extend from academic laboratories to public policy. Ongoing analysis of the nutrition science evidence crisis illustrates how fragile data undermines evidence-based dietary guidelines and erodes public trust. Consequently, researchers now advocate for a total reconstruction of metabolic research capacity, aiming to modernise how we track dietary intake and physiological responses in real-world environments.

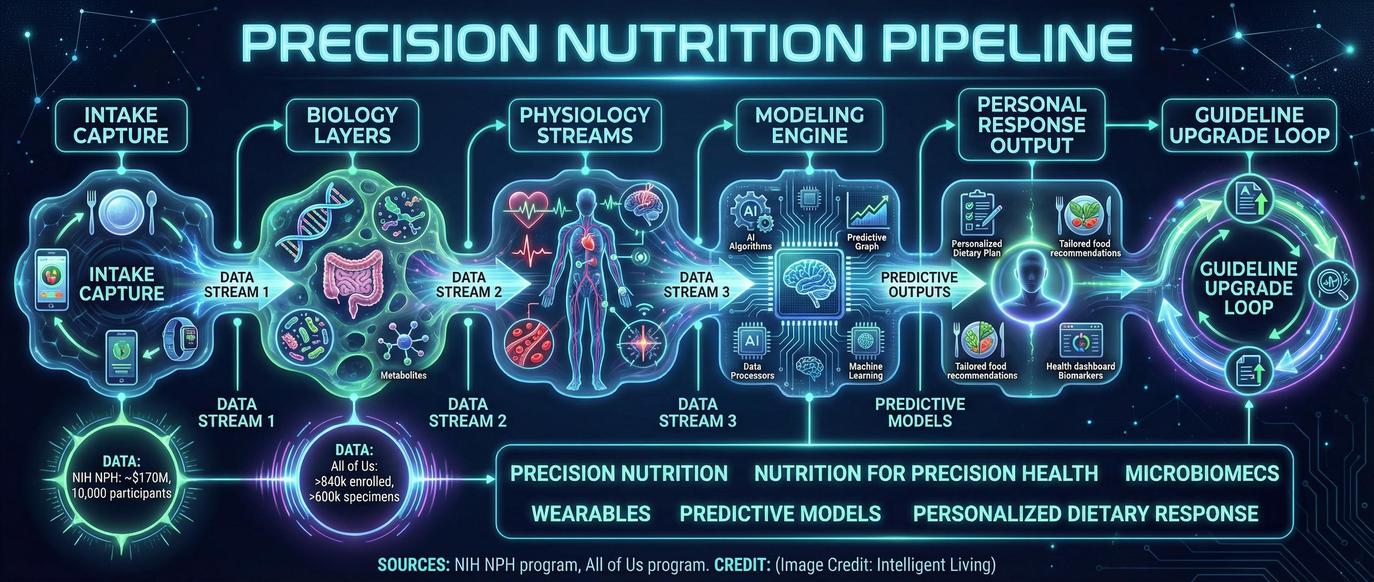

Shifting toward a model that prioritises objective measurement and reproducible studies allows scientists to begin mapping a reliable pathway out of this data desert. Securing this transformation is essential for the NIH Nutrition for Precision Health initiative, which seeks to predict individual responses to diet through the integration of genomic and microbiome data.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

Critical Metrics Defining the Modern Metabolic Research Gap

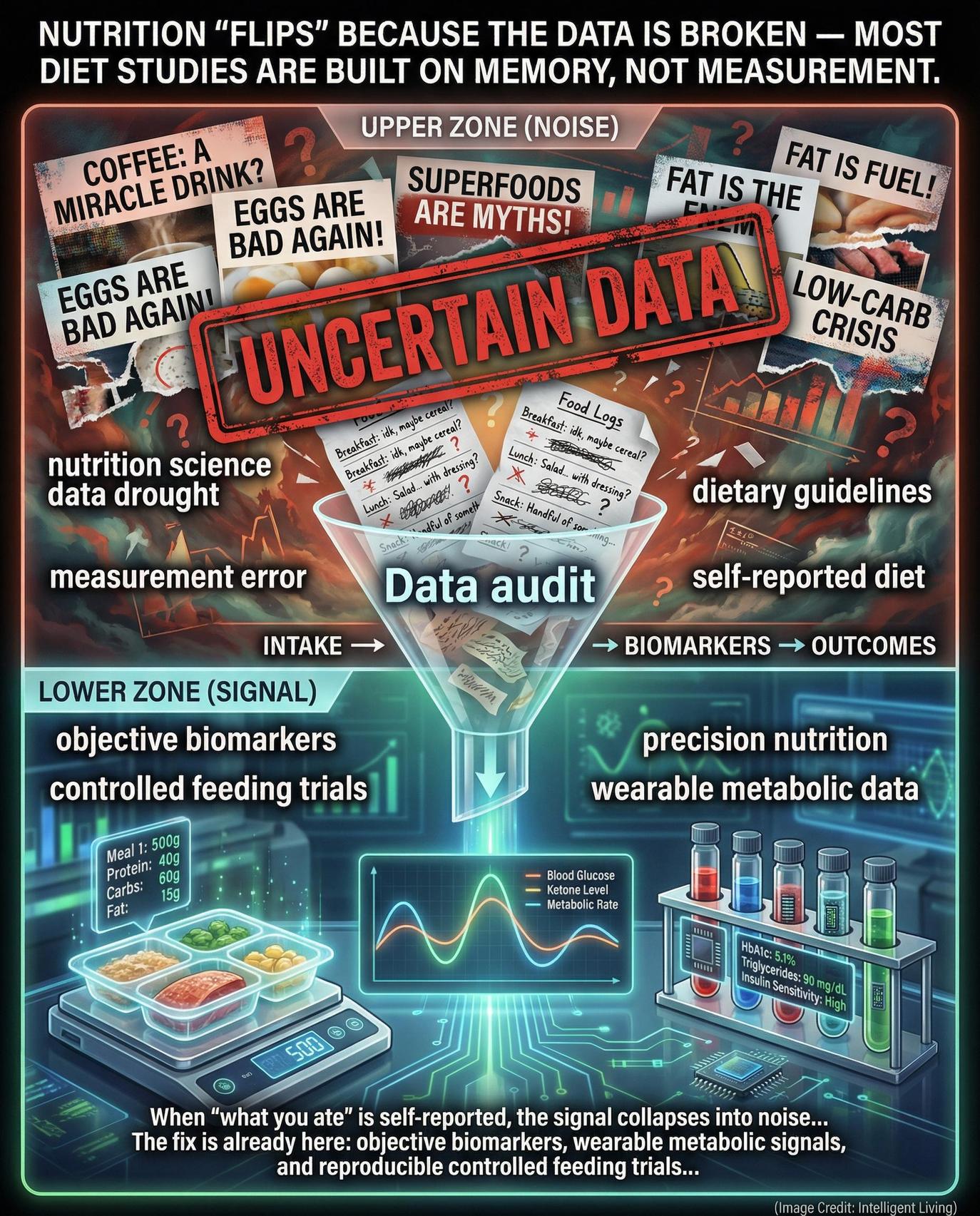

Quantifying the current deficit in metabolic research requires a close examination of federal investment and policy blueprints. The following data points highlight the stark contrast between the public health burden of nutrition-related disease and the resources allocated to solving it:

NIH Nutrition Investment: According to the most recent NIH nutrition portfolio report, the agency allocated roughly $2.2 billion to nutrition research in 2023—only 4.07% of its total research spending.

FAS CEHN Proposal: A leading policy proposal from the Federation of American Scientists calls for a $5 billion-per-year investment to create a network of Centres of Excellence in Human Nutrition (CEHN) equipped with metabolic kitchens and inpatient trial capacity.

Measurement Error Problem: Guidance from the National Cancer Institute emphasises that self-reported food intake introduces significant error that weakens the reliability of diet–disease findings across large observational cohorts.

Precision Nutrition Frontier: The NIH Nutrition for Precision Health program is linking genomic, microbiome, and lifestyle data to predict individual responses to diet and push nutrition toward a personalised future.

Such stark figures illustrate why the transition to precision nutrition requires more than just new ideas; it requires a massive expansion of physical infrastructure. Until these funding gaps are closed, the evidence-based dietary guidelines used by clinicians will remain constrained by a lack of high-fidelity data.

Deconstructing The Nutrition Science Data Drought: A Fragile Evidentiary Foundation

Nutrition science has never lacked curiosity or public interest. What it lacks is the plumbing—a consistent data pipeline that connects what people eat, how their bodies respond, and what outcomes emerge over time.

The term “data drought” specifically describes the structural shortage of controlled, interoperable, and reproducible nutrition studies capable of withstanding rigorous scientific scrutiny.

Subjective Recall and The Fragility of Memory-Based Evidence

A multi-decade dependency on subjective dietary recall has anchored nutrition science to a fragile evidentiary foundation. This reliance is problematic because individuals frequently:

Misremember Consumption: Forgetting specific foods or ingredients eaten throughout the day.

Underestimate Portions: Failing to accurately gauge the volume or weight of servings.

Unintentionally Misreport: Altering reported intake due to perceived social expectations or cognitive fatigue.

Such systematic errors introduce significant bias into large-scale studies, weakening the overall signal. Acknowledging that inherent measurement error doesn’t render the science invalid remains crucial, yet it certainly makes the resulting conclusions far more ambiguous. When evidence remains fuzzy, public health advice frequently swings between extremes, leaving the general public understandably sceptical of any new dietary recommendations.

A better nutrition data system would function more like a modern weather network, capturing continuous, high-resolution signals from multiple sensors instead of sporadic self-reports. Emerging programmes such as the NIH Nutrition for Precision Health initiative build this infrastructure by integrating wearable devices, metabolomics, and microbiome data to capture a more holistic picture of human health that incorporates gut–brain–immune signalling in social anxiety and other high-resolution biological signals.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

Establishing Clinical Rigour: Why Nutrition Science Research Demands Metabolic Control

Establishing the same level of rigour found in pharmaceutical trials requires a logistical overhaul of how diet is managed. To achieve drug-grade precision, a nutrition science research protocol must successfully coordinate several high-stakes variables:

Menu Engineering: Designing chemically precise meals that meet specific nutrient targets.

Ingredient Sourcing: Ensuring every raw material is standardised for consistency.

Meal Preparation: Utilising metabolic kitchens to eliminate outside variables.

Adherence Monitoring: Tracking participant intake within clinical environments for weeks or months.

Managing these factors demands a specialised clinical capacity that most modern research centres simply no longer possess. Without these controls, researchers are forced to rely on inference rather than the direct causality needed for evidence-based dietary guidelines.

The Historical Erosion of National Nutrition Research Infrastructure

Over the past two decades, this infrastructure has quietly eroded. Such infrastructure shortfalls mean that most dietary studies still rely on observational data—comparing what people say they eat with their health outcomes—rather than truly testing cause and effect.

In the early 2000s, the National Institutes of Health phased out its General Clinical Research Centers (GCRCs), replacing them with Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs). While the CTSAs expanded access to general research infrastructure, they rarely maintained the kind of dedicated kitchens and feeding facilities needed for tightly controlled nutrition experiments.

As a result, today’s nutrition scientists often lack the tools to run the very trials that could answer society’s biggest diet questions. Understanding the chemistry of baking by interviewing people about their favourite cookies instead of running the experiments yourself serves as a fitting metaphor for this clinical gap.

What We Lost when Metabolic-Kitchen Capacity Withered

For decades, metabolic kitchens served as the backbone of nutrition research. These specialised facilities prepared every meal for study participants, ensuring that nutrient intake was precisely measured. But as funding priorities shifted, many of these kitchens closed or were repurposed for other kinds of research.

The result is a generation of nutrition scientists working without their most essential laboratory. When every calorie, micronutrient, and ingredient can be controlled, researchers can isolate the effects of specific dietary components with unprecedented precision. Without that level of control, nutrition research becomes a guessing game—valuable, yes, but limited in its power to prove causality.

The NIH-supported Clinical and Translational Science Awards programme still provides broad research infrastructure, but few centres retain the full metabolic-ward capacity once common under the GCRC system. The proposed CEHN network from the Federation of American Scientists aims to rebuild these capabilities, creating national hubs capable of running high-quality, multi-site diet trials.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

The CEHN Proposal—A National Nutrition Trial Network

The Centres of Excellence in Human Nutrition (CEHN) proposal envisions a nationwide network of research hubs designed to transform how nutrition science is conducted. Each CEHN site would include metabolic kitchens, inpatient facilities, and high-throughput data analysis platforms capable of running controlled feeding trials year-round, as outlined in the policy blueprint for Centers of Excellence in Human Nutrition from the Federation of American Scientists.

Coordinated Interventions: Scaling Dietary Testing for Diverse Populations

The goal is to move beyond small, isolated studies and toward a coordinated ecosystem that can test dietary interventions at scale. Imagine being able to run hundreds of precisely controlled diet trials across diverse populations. Integrating genomic, metabolic, and behavioural data within this infrastructure would allow researchers to identify not only what diets work on average but also why they work differently for different people.

If implemented, the CEHN model could fill a decades-old void in nutrition science, giving policymakers and clinicians a more reliable foundation for dietary guidance. It would also complement the broader push for stronger data governance and transparency across biomedical research.

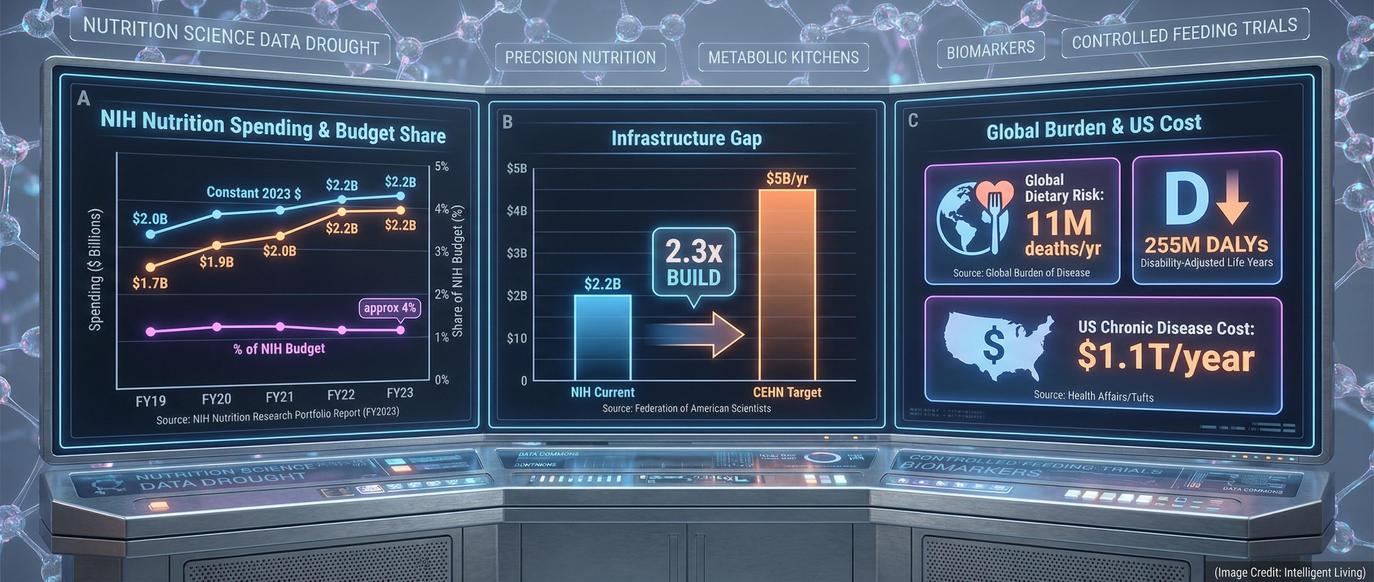

Enhancing Evidence Integrity through Objective Dietary Assessment Biomarkers

Perhaps the most persistent weakness in nutrition science isn’t funding or infrastructure—it is measurement error. Relying on memory-based food surveys is like trying to balance a chequebook using only receipts you happen to remember. Guidance from the National Cancer Institute dietary assessment primer explains how self-reported dietary data introduces systematic bias that can obscure real diet–disease relationships.

Moving Beyond Memory: The Role of Biological Markers

To overcome this, researchers are turning to objective biological markers—known as biomarkers—that can validate or replace self-reporting. For example, doubly labelled water can measure total energy expenditure, while urinary nitrogen provides a reliable marker of protein intake. These biomarkers serve as independent checks, helping researchers calibrate and correct inaccuracies through precision gut health strategies using fermented nutrients that track biomarkers and symptoms in unison.

Technological advances are also making it easier to track what people eat without depending solely on recall. Several digital tools are bringing the concept of ‘real-time dietary monitoring’ closer to reality:

Smartphone Food Diaries: Allowing for immediate logging of intake.

Wearable Glucose Monitors: Providing real-time metabolic response data.

AI-Powered Image Recognition: Automating portion and nutrient analysis through photography.

Comprehensive biomarker memberships now bundle extensive lab testing with AI interpretation. These data-driven biomarker platforms designed for preventive health monitoring demonstrate how utilising granular blood data supports a more precise clinical shift. When combined with traditional metrics, these innovations reduce uncertainty and elevate nutrition science to the same level of precision common in other biomedical fields.

Beyond the technical requirements, resolving the measurement layer remains a fundamental matter of public trust. Better data means more consistent findings, and more consistent findings mean the public can once again rely on nutrition advice that stands the test of time.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

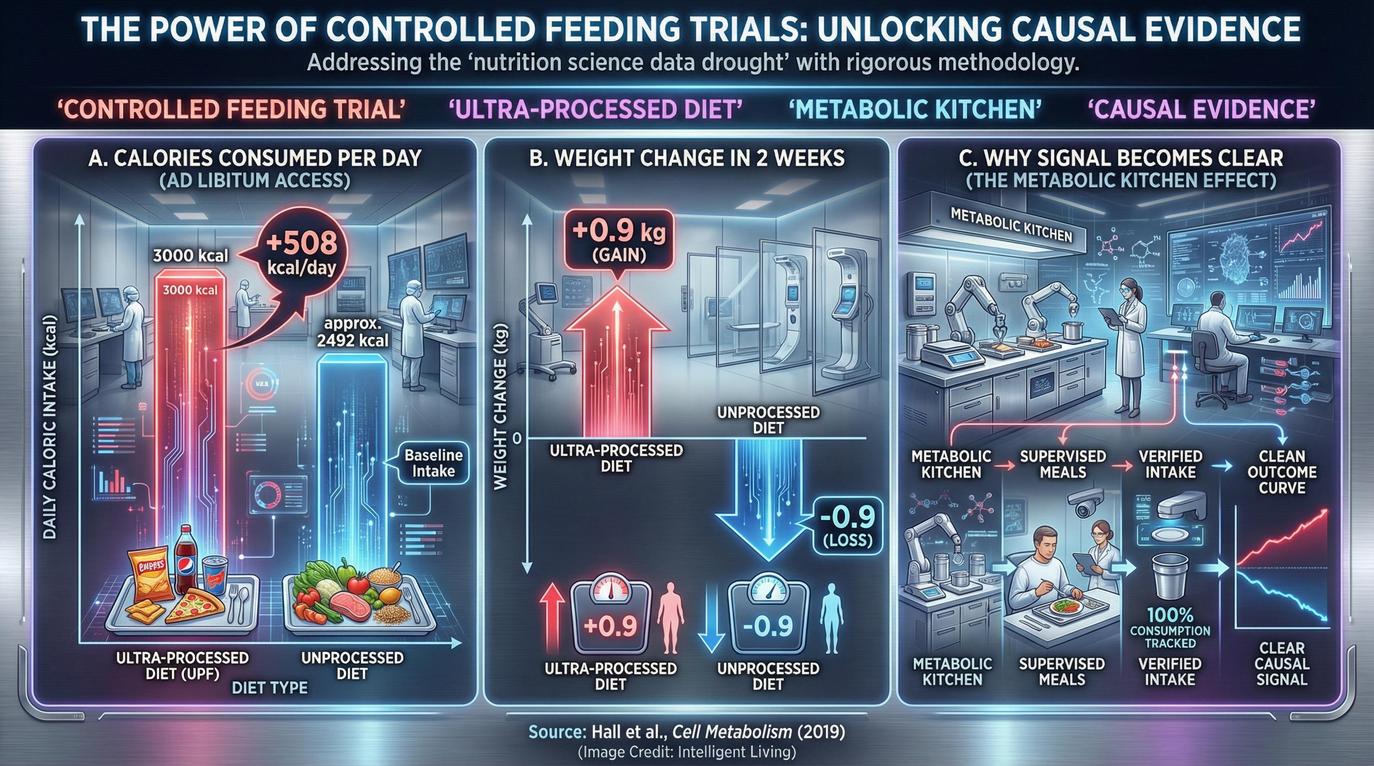

Achieving Metabolic Clarity: The Power of Controlled Feeding Trials

The best evidence for why controlled diet trials matter comes from research that has already managed to do them. In 2019, scientists published a controlled inpatient trial on ultra-processed versus unprocessed diets in Cell Metabolism that compared two eating patterns under tightly monitored conditions. Every meal was prepared and supervised, ensuring participants ate only what researchers provided.

The findings were striking. Participants on ultra-processed diets consumed approximately 500 more calories per day and gained significant weight, despite the fact that both diets were carefully matched for macronutrients.

Controlled inpatient settings demonstrate something crucial: when you control the food environment, the biological signal becomes clear. Such results help explain why nutrition advice can fluctuate, because most studies simply cannot control every factor. Controlled feeding trials cut through the noise, providing direct evidence about how different foods affect metabolism, hunger, and weight regulation.

Mechanistic work on a gut–brain pathway that drives cravings for high-fat, high-sugar foods further illustrates how dietary patterns can hijack appetite regulation. Such discrepancies occur even when calorie counts appear similar on paper, demonstrating the need for granular metabolic data.

Expanding this metabolic capacity through CEHN hubs would produce the empirical grounding required to anchor national dietary guidelines in causality. This evolution aligns with research where a prebiotic fibre trial in older adults that modestly improved memory performance demonstrated the cognitive impact of specific dietary intervention.

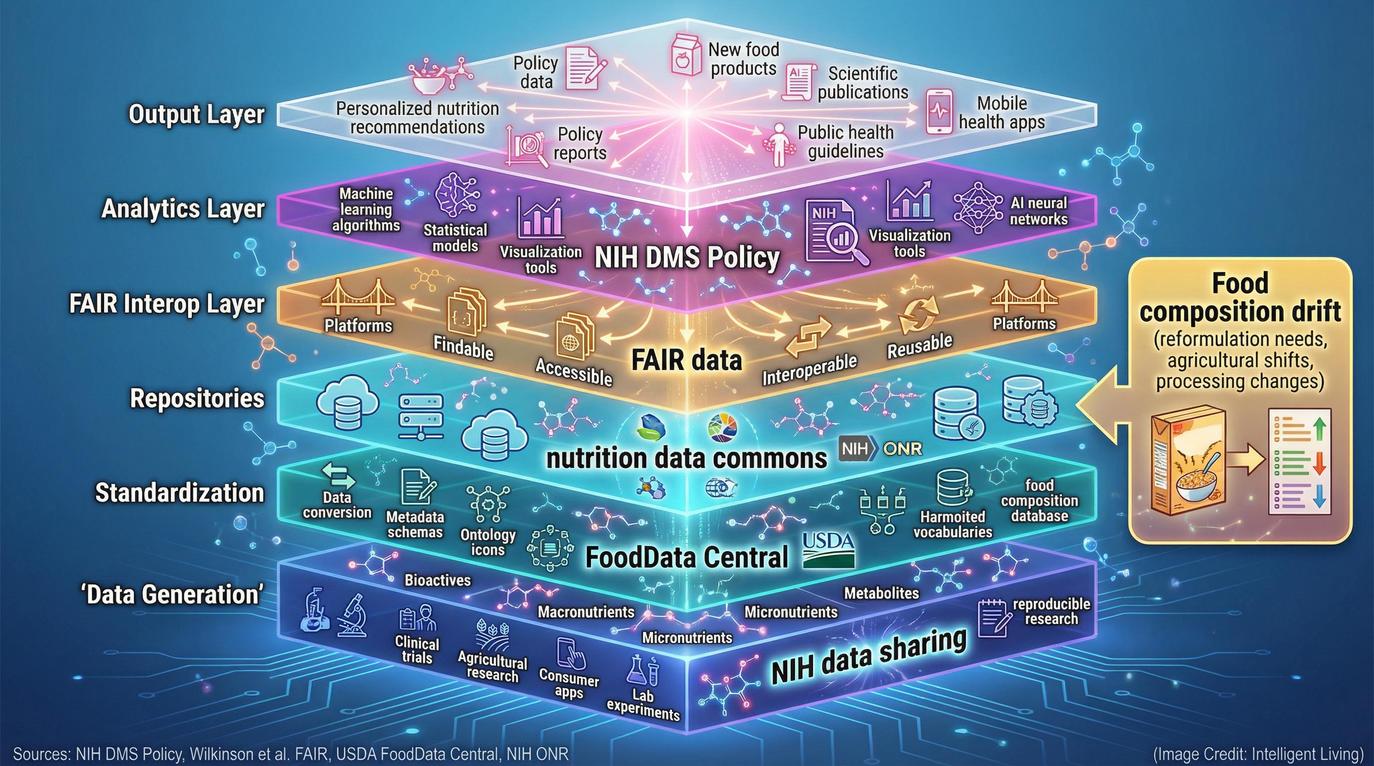

The Data Commons Layer: DMS + FAIR + Where Researchers Can Actually Share

Building the infrastructure for rigorous nutrition science extends beyond kitchens and clinics; it requires data systems that are inherently interoperable. The data management and sharing policy at the National Institutes of Health now mandates that researchers receiving federal funding create accessible plans for data storage.

Federal mandates now aim to dissolve isolated data silos, transforming them into open resources for the global research community. By creating a unified data commons, nutrition science can finally move toward a model of continuous, collaborative analysis.

The broader framework guiding this effort is known as the FAIR principles, a concept formalised in the original FAIR data principles paper, which stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. These guidelines ensure that data generated by one team can be understood and reused by another, enabling reproducibility and collaboration across institutions. The NIH nutrition science data and biospecimen resources portal already catalogues key datasets and tools to support this kind of sharing.

Bridging The Gap Between Population Data and Clinical Practice

Increased transparency directly benefits the public, as open data reduces research redundancy and accelerates discoveries. Implementing data-driven chronic disease management through healthcare analytics hints at how a unified nutrition data commons could eventually support clinicians as well as researchers.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

The Food Composition Truth Layer: What’s in the Food Still Matters

Nutrition science doesn’t just depend on knowing what people eat—it depends on knowing exactly what is in the food. Databases such as the FoodData Central database and its global branded food products database provide the backbone for most nutrient calculations in research.

Yet food products change constantly as companies reformulate recipes, add ingredients, or fortify products. Constant recipe fluctuations can introduce another layer of uncertainty into nutrition studies if databases are not regularly updated. Continuous investment in comprehensive, publicly accessible food composition data ensures that the numbers behind every study remain as accurate as possible.

Improving food composition data also supports precision nutrition research, helping scientists connect detailed nutrient profiles with biomarkers and health outcomes. In this sense, upgrading databases is as essential as upgrading laboratories; it is part of the same pursuit of evidence integrity.

Scaling Precision Nutrition: Utilising The NPH Initiative as A Predictive Model

The NIH Nutrition for Precision Health initiative (NPH) offers a glimpse into the future of nutrition research. Built upon the massive All of Us Research Program, it aims to enrol thousands of participants to understand how genetics, microbiomes, and lifestyles interact to shape nutritional needs.

NPH represents a practical test of how nutrition research could operate in a data-rich ecosystem. Combining traditional dietary assessments with molecular data and machine learning allows for the creation of sophisticated predictive models. These systems could one day generate highly personalised dietary guidance for the general public. Far from science fiction, these predictive models represent a logical next step toward improving public health using individualised data.

If programmes like NPH succeed, they will not only enhance clinical nutrition science but also guide policy by showing how population-scale datasets can inform everyday dietary recommendations.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

What this Means for Readers Right Now

For everyday readers, the transformation underway in nutrition science means that future dietary advice will likely be based on far more reliable evidence. The next generation of studies will measure what people eat and how their bodies respond with unprecedented accuracy. Such a systemic shift could finally bring consistency to nutrition headlines and restore confidence in evidence-based dietary guidance.

Applying Data-Driven Principles to Everyday Dietary Choices

In the meantime, consumers can apply the same principles guiding researchers:

Seek Data-Driven Advice: Prioritise recommendations backed by clinical trial data.

Question Unverified Claims: Remain sceptical of findings that lack objective biomarkers.

Favour Longevity Patterns: Focus on dietary habits grounded in long-term health outcomes.

Prioritising Mediterranean Diet 3.0 research on longevity and heart health and following practical guides that explain how different grains affect blood sugar, gut health, and long-term risk allows consumers to apply the same rigour as researchers.

Where Momentum is Building

The pieces of a modern nutrition research ecosystem are finally falling into place through several key initiatives:

The CEHN Proposal: Rebuilding the national infrastructure for controlled trials.

The NIH Data Management Framework: Enforcing transparency and interoperability.

The ONR Biospecimen Portal: Centralising access to key research datasets.

Systems-level blueprints, including a sustainable food system roadmap linking agriculture to public health outcomes, illustrate how nutrition data informs decisions far beyond the dinner table. As these modular systems mature, the historical gap separating nutrition science from other rigorous biomedical disciplines will inevitably close, ushering in an era of unprecedented evidentiary strength.

For the public, this means that advice about food and health will gradually move away from short-lived fads and toward lasting scientific consensus. Nutrition will always involve personal choice, but it can soon rest on a foundation of data that everyone—scientists, policymakers, and eaters alike—can trust.

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

(Credit: Intelligent Living)

Advancing Empirical Causality in Nutrition Science Research

Ending the data drought in nutrition science research is an engineering challenge that requires immediate national investment. Rebuilding trial infrastructure, improving measurement precision, and enforcing modern data-sharing standards allows researchers to turn fragmented findings into actionable knowledge.

Transitioning to these rigorous standards ensures that future evidence-based dietary guidelines are anchored in metabolic reality rather than subjective recall, restoring the public’s ability to rely on nutritional advice that stands the test of time.

Public health depends on the integrity of this data pipeline. As researchers move toward high-throughput controlled feeding trials and standardised FAIR data principles, the gap between nutrition and other rigorous biomedical disciplines will inevitably close.

Continued evolution in metabolic research will empower individuals to make dietary choices based on hard evidence. Achieving such a transformation fosters a future where personal wellness is guided by precision, transparency, and scientific consensus.

Essential Insights into Modern Metabolic Research

Why Do Nutrition Science Research Findings Often Conflict?

A majority of legacy studies rely on subjective self-reporting, which introduces significant measurement error and bias. Transitioning toward objective biomarkers and controlled feeding trials will eventually eliminate these contradictions.

What Is the Role of a Metabolic Kitchen Facility?

These specialised laboratories prepare every meal for study participants with clinical precision. This level of control allows researchers to isolate the metabolic effects of specific nutrients with high accuracy.

How Does The CEHN Proposal Transform Nutrition Data?

The Centers of Excellence in Human Nutrition (CEHN) model creates a coordinated network for large-scale clinical trials. This infrastructure improves data reproducibility and supports more reliable evidence-based dietary guidelines.

What are The NIH FAIR Data Principles?

FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable data standards. These protocols ensure that nutrition datasets are no longer isolated, allowing for global collaboration and transparency.

How Does Precision Nutrition Benefit the General Public?

Precision nutrition uses individual genomic and microbiome data to tailor dietary advice. Unlike one-size-fits-all guidelines, this approach predicts how specific bodies respond to different foods for better health outcomes.