A few decades ago, patients with metastatic cancer had few reliable treatment options beyond chemotherapy, a treatment regimen that often brought limited success and significant side effects. Then came immunotherapy, a breakthrough treatment that harnesses the body’s immune system to fight tumors. It has been a game changer and in many cases a lifesaver for patients with advanced melanomas and other cancers.

“Immunotherapy has had a huge impact in fighting metastatic cancers and leukemias when no other treatments have worked,” says Michelle Krogsgaard, PhD, an immunologist at NYU Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

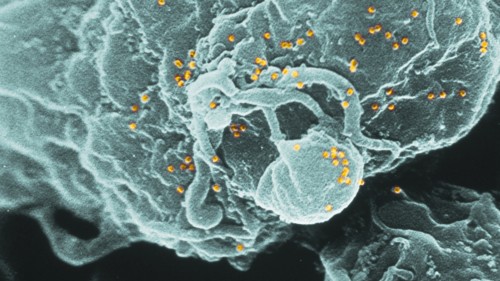

There’s a catch, however. T cells, the “police officers” of our immune system, are mainly responsible for recognizing and killing cancer cells and other threats. To do their job, T cells rely on cell-surface proteins called receptors, which recognize and grab hold of the distinctive flags on the surface of cancer cells, known as antigens. These antigens help the immune system distinguish cancerous cells from healthy cells. Yet deceptive tumors can mutate or hide these flags from appearing outside cells, thus cloaking themselves from T cells and fending off immunotherapy.

In several recent studies, Dr. Krogsgaard and her team have made key discoveries about how T cells recognize specific cancer cells by their telltale antigens, how that process can go awry, and how certain antigen features may help the immune system strike tumors more precisely. “We’re hoping to get deep molecular insights into how T-cell therapies work so we can develop treatments that are better, safer, and potentially tailored to each patient,” Dr. Krogsgaard explains.

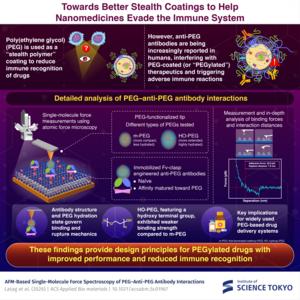

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy, a common type of immunotherapy, often uses antibodies—immune proteins that recognize and block specific target proteins to prevent cancer cells from binding to and “turning off” T cells and other immune cells, thereby closing off a critical escape route. When clinicians combined three checkpoint inhibitors, including an antibody targeting a cancer-linked protein called LAG-3, they saw greater responses in patients and fewer side effects. “But no one really knew how it worked,” Dr. Krogsgaard says. “To make these therapies better, you have to understand the mechanism behind them.”

In a new study submitted for publication, Dr. Krogsgaard demonstrated that a second protein, FGL-1, partners with LAG-3 to help cancer cells evade T-cell attacks. Deciphering the basis of that physical interaction and how it triggers an ensuing pathway of signals and evasive actions, she says, could lead to novel cancer targets beyond that initial protein pairing.

Blocking individual cancer proteins one at a time sometimes leads other proteins to take over and thwart the therapeutic effort, much like playing the arcade game Whac-A-Mole. “But if you can find something that targets multiple signaling pathways with shared features, you can hit all of them,” Dr. Krogsgaard says.

The Krogsgaard Lab has already discovered several promising new cancer targets. In a landmark 2023 study published in Nature Communications, the team identified an unusual cancer marker: a short piece of protein that carries a tiny chemical tag called a phosphate. This tag, which only appears on the tumor version of the protein, lets T cells clearly recognize and attack the cancer. Dr. Krogsgaard and colleagues believe the finding could point to a broader therapeutic target that would spare unaffected cells. As a proof-of-principle experiment, the lab engineered T cells that recognize the distinctive protein tag. In mice with leukemia, the engineered T cells eliminated the cancer.

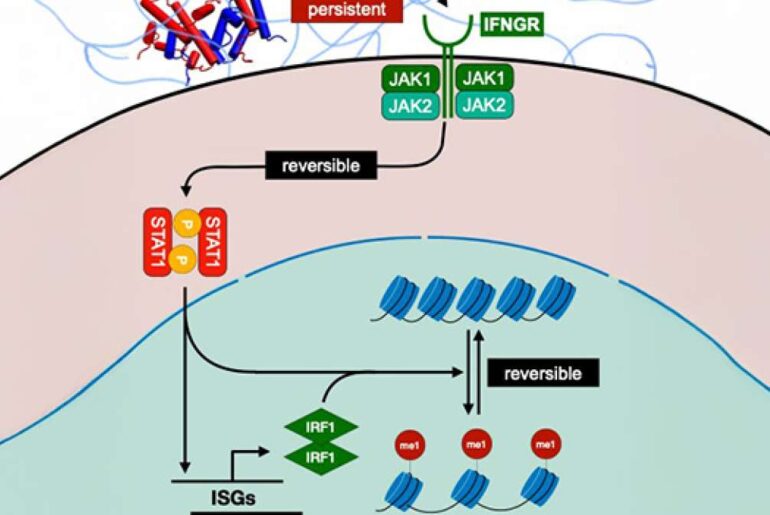

In another breakthrough study, published in 2024 in Nature Communications, Dr. Krogsgaard and colleagues identified a unique cancer antigen created by a genetic mutation that alters the protein’s configuration. That alteration enabled enhanced recognition by the T-cell receptor, thereby boosting the immune response. Concurrent studies published by Dr. Krogsgaard and collaborators used highly sophisticated biophysical and imaging techniques to show that mechanical forces and the natural movement of proteins in the cell membrane affect how the T-cell receptor grips and flexes. Those movements, in turn, help activate T cells without changing what they recognize.

“We can use this combined knowledge to design cancer cell antigens that are more recognizable and elicit efficient T-cell responses,” Dr. Krogsgaard explains. “This approach could lead to safer therapies by boosting receptor interactions without manipulating them directly.”

Recently, the Pew Charitable Trusts gave Dr. Krogsgaard and fellow NYU Langone cancer biologist Richard L. Possemato, PhD, a prestigious Innovation Fund award to support their interdisciplinary efforts to understand how limited nutrients in tumors weaken T cells’ cancer-fighting ability. Dr. Krogsgaard’s lab is also working closely with clinical and pharmaceutical partners to improve the selection of cancer drug targets by identifying antigens that provoke the best T-cell response.

“Our approach is unique. We invest heavily in understanding what differentiates a good tumor antigen from a bad one by studying the underlying mechanisms,” Dr. Krogsgaard says. “We also collaborate closely with clinicians and oncologists to test patient samples. If we find something useful, they can translate it directly to patients as therapeutics.”

The Explorations That Inspire Our Trailblazing Scientists

Dr. Michelle Krogsgaard’s cutting-edge work to improve immunotherapy treatments is highlighted in the video series Behind the Breakthrough: NYU Langone Researchers Tell Their Stories. Each episode describes the personal inspirations and pivotal discoveries fueling NYU Langone Health’s lifesaving mission. By sharing these stories from leading scientists, the series illuminates how key moments and experiences can spark world-changing research.