Animal ingredients like salmon sperm, tallow, and collagen are trending in clean beauty. But their rise exposes a rift between marketing claims, ethical sourcing, and the climate cost of animal-based skincare.

Beef tallow is back in the spotlight. Whole Foods Market listed it as its top trend for 2026. Once a pantry essential prized for its rich flavor and resilience under high heat, the rendered animal fat is reemerging as home cooks and chefs alike are rediscovering its versatility — from frying and baking to crafting flaky pastries and crisp fries.

The revival dovetails with the growing interest in ancestral eating and the “nose-to-tail” ethos, which values using every part of the animal, including fat that would otherwise go to waste. On social media, whipped and herb-infused versions are trending, celebrated for their deep flavor and old-world appeal. Even restaurants are swapping out modern oils for tallow to elevate comfort food classics — never mind the increasing number of studies that point to animal agriculture’s environmental impact.

Miley Cyrus is the latest celebrity to try salmon sperm facials

Miley Cyrus is the latest celebrity to try salmon sperm facials

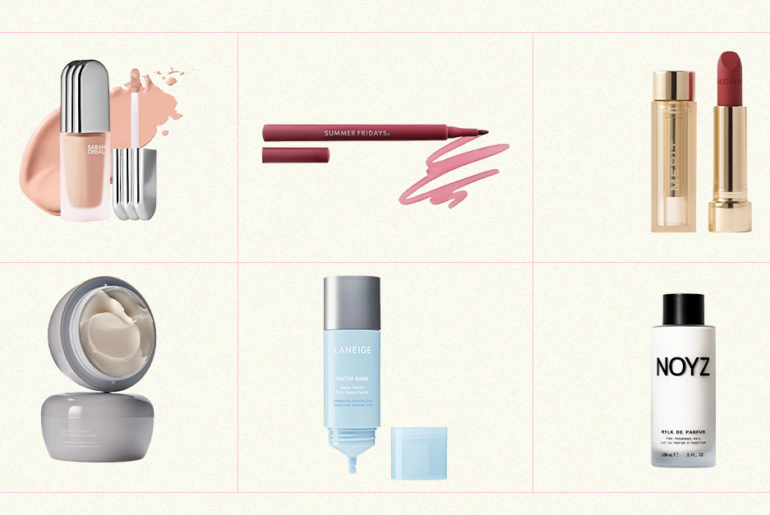

Even without the environmental considerations, it does not exactly sound glamorous. Yet, across social media and increasingly on skincare labels, tallow is reemerging as a covetable, even luxury, asset. Along with salmon sperm, honey, lanolin, and collagen are also being folded into clean-beauty rhetoric and marketed as nourishing, ancestral, and undeniably potent.

Last summer, Miley Cyrus quipped on stage during a surprise performance in New York City that her glowing skin was due to salmon sperm; the audience wasn’t sure whether or not she was joking. “Taste strange, but my skin looks good,” Cyrus said, confirming her fascination with polynucleotide — or PDRN. The buzz is real: PDRN masks and serums like Medicube’s duo have surged in popularity, appearing on Amazon bestseller lists following TikTok viral moments.

Kim Kardashian admitted she also had a salmon sperm facial, which involves injecting salmon sperm into the face. According to some experts, fish’s reproductive cells have been linked to improved skin, hydration, plumpness, texture, and reduced wrinkles. “The effects on the skin are thought to be due to high DNA levels,” New York City-based dermatologist Joshua Zeichner, MD, told PopSugar. “DNA is composed of amino acids, which have long been used in skin care for their hydrating and cell-renewing benefits,” he said.

Still, adopting salmon sperm as beauty fodder underscores a broader cultural shift: animal-based formulations, once fringe, are now positioned as scientifically advanced and celebrity-endorsed — even when clinical validation remains nascent. But the gloss of star power and biohacking adds weight to clean-beauty messaging, even as ethical questions about sourcing, regulation, and efficacy linger at the treatment’s core.

As brands double down on claims of purity and minimalism, a critical question emerges: Can a product be called “clean” if it comes from an animal? Specifically, a dead one?

RDNE Stock project

RDNE Stock project

Tallow is perhaps the most controversial example. Sourced from rendered beef fat, it is gaining traction among consumers who tout its moisturizing capabilities and ancestral wellness appeal. Some devotees point to historical use in balms and soaps, while others associate tallow with the paleo, carnivore, or animal-based diet trends embraced by influencers like Paul Saladino.

“There’s a growing interest in traditional whole-ingredient skin care inspired by what our ancestors used before commercial skin care existed,” celebrity esthetician and brand founder Sofie Pavitt, told Vogue. “People are gravitating toward ‘skinimalism’ and using pure, unprocessed ingredients like tallow.”

Tokenizing ancestral practices

But ancestry does not mean superior performance or quality; tallow was used primarily because it was readily available, affordable, and aligned with a no-waste approach — our ancestors used every part of the animal out of necessity. Tallow was a practical moisturizer and soap base because extracting plant oils and synthetics wasn’t as feasible. But modern alternatives often work as well or better than tallow, with added benefits like stability, texture. Comparable ingredients include shea butter, jojoba oil, and squalane — all of which are also natural as well as non-comedogenic and rich in fatty acids.

These plant-based emollients mimic skin’s natural lipids without the downsides of animal sourcing or scent. And, according to the experts, tallow isn’t a cure-all; it can even bring risks, Chris Tomassian, MD, board-certified dermatologist and founder of the Dermatology Collective, told Vogue.

“There are many variables that come into play when creating beef tallow products, and if not properly purified or stored, it can spoil or be contaminated,” he says. “It also has no consistent formulation, no regulation if made in small batches, can have a strong odor, and is not supported by dermatologists or clinical studies for skin-care use.”

But that hasn’t stopped the #beeftallow craze. TikTok has played a decisive role in its MAHA-fueled revival, with the platform reporting nearly 122 million posts on the topic.

Jennifer Aniston’s Vital Proteins’ is a top-selling collagen supplement

Jennifer Aniston’s Vital Proteins’ is a top-selling collagen supplement

Collagen, often made from bovine or marine sources, is another booming animal market. While topical collagen in creams and serums can hydrate the skin superficially, most dermatologists agree that its molecular size prevents it from penetrating deep enough to meaningfully affect collagen production in the dermis. Oral collagen, which promises similar results, is also a booming “miracle cure” market. The global collagen market was valued at over $9.1 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual rate of 9.2 percent through 2030.

“There is no evidence that collagen creams or supplements benefit skin,” board-certified dermatologist Nancy Samolitis, co-founder of Facile Skin, told Bazaar. “Collagen is a large molecule that can not penetrate deep into the skin when applied topically, and oral collagen gets digested by acids in the stomach.” Yet with high-profile supporters like Jennifer Aniston, the category shows no signs of slowing, despite the lack of empirical evidence and other issues, like the industry’s ties to deforestation.

Royal Lancaster beehive

Royal Lancaster beehive

Then there are ingredients like honey and lanolin, which, while more widely accepted by clean beauty brands, still walk a tightrope in ethical debates. Honey is antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory, making it a favorite in everything from masks and cleansers to lip balms. It’s used by brands including Burt’s Bees, Farmacy, and Guerlain. But bee welfare and over-harvesting remain legitimate concerns. Industrial apiculture has been linked to colony collapse disorder, pesticide exposure, and reduced biodiversity. The same goes for lanolin, a wool-derived emollient used in nipple creams and lip balms, which raises questions about animal treatment in large-scale sheep farming.

While neither of these products requires the animal to be killed, death is not uncommon, especially when retrieving honey from beehives. The wool industry is notoriously tied to mutilative practices like mulesing. And, like cows, sheep are among the biggest methane producers; methane is over 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at warming the planet over a 20-year period, and about 28 to 36 times more potent over 100 years, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Although methane has a shorter atmospheric lifespan — around 12 years — it traps significantly more heat in the short term, making it a critical target for near-term climate action.

How much should climate impact factor into the clean beauty label?

“Clean” or not, all animal ingredients pose big climate risks. Animal agriculture contributes significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions — its reach extends far beyond beauty supply chains. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, livestock accounts for roughly 18 percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions — including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide — and occupies about 70 percent of global agricultural land. Methane from enteric fermentation and manure alone represents about 37 percent of agricultural methane, while nitrous oxide from animal waste and fertilizers contributes 65 percent of agricultural nitrous emissions. These forces combine to accelerate climate warming, biodiversity loss, water use, and soil degradation.

That impact is magnified by the scale and inefficiency of the system. Producing one pound of beef uses an astonishing 2,500 gallons of water, compared with fewer than 500 for eggs and under one thousand for cheese. Globally, nearly 15 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions come from animal-based food production — more than the emissions produced by the entire transportation sector. The massive land use demands also drive deforestation: nearly 30 percent of the Earth’s land surface is used for grazing livestock, and with 70 percent of that dedicated to pastures and feed crops, such land conversions have been a prime factor in habitat loss and species decline.

Critics argue that relying on accounting methods that minimize methane’s role amounts to a dangerous oversight. As climate expert Paul Behrens warned in an open letter to the Financial Times: “It’s like saying ‘I’m pouring one hundred barrels of pollution into this river, and it’s killing life. If I then go and pour just ninety barrels, then I should get credited for that.’” Behrens and fellow scientists caution that using methods like global warming potential to justify flatlining emissions rather than reducing them weakens momentum toward meaningful climate commitments.

Tata Harper set out to redefine skincare from her Vermont farm

Tata Harper set out to redefine skincare from her Vermont farm

Brands operating in the clean-beauty space often skirt around these data by emphasizing sourcing transparency or relying on co-products — materials that would otherwise be waste. This is particularly common with tallow, which some small-batch beauty labels claim is sourced from grass-fed cows already being processed for meat. Grass-fed cows make up less than five percent of cattle, and sourcing practices are rarely certified or disclosed in detail.

And that is the crux of the issue: transparency. Without industry-wide standards for what constitutes “clean,” brands are left to define their own parameters, and consumers are left to navigate increasingly murky waters. While clean beauty started as a way to eliminate harmful chemicals, it has evolved into a broader conversation about what consumers value: sustainability, transparency, and cruelty-free standards. Those certifications have long been shorthand for “clean”, yet many newer brands are leaning into non-vegan heritage ingredients without disclosing the ethical compromises involved. Tallow-based brand Primally Pure, for instance, avoids parabens, synthetic fragrances, and preservatives, but its products are made from animal fat.

Ancestral rhetoric, “farm to face” branding, and minimalist, Earth-toned packaging tie these products to a larger narrative of purity and ritual. Yet few of the brands embracing this aesthetic disclose whether their ingredients are USDA certified, ethically harvested, or tested for contaminants.

“Unfortunately, ‘clean’ has become a buzzword,” Tata Harper, founder of her namesake skincare brand, told Ethos. The label produces its plant-based formulations on her Vermont farm, growing or sourcing its ingredients from organic producers. She says certifications like EcoCert help consumers navigate the sea of skincare options. Labels like Clean at Sephora and marketplaces like Credo emphasize clean-label products. But for those invested in clean beauty’s original mission — to protect human and planetary health — the return of animal-derived ingredients leaves more questions than answers.

“We’ve come a long way with skin-care formulations,” says Pavitt. “This seems like a total step back — and not in a good way — to use something like beef tallow on the skin.”

Related on Ethos: